Speaking of Defense In Left Field…

You’ve heard it all winter long: the Diamondbacks thrive on good defense. Gerardo Parra was simply incredible in right field last year en route to his second Gold Glove. Paul Goldschmidt, never one to be left out, earned one of his own at first base. A.J. Pollock was stellar in center, Gregorius was solid at short, Prado was just fine at third, Hill good at second and Cody Ross played a surprisingly strong left field once Jason Kubel was out of the way. I chronicled all of this two weeks ago and since this is all in the past, nothing’s really changed.

But now we have real baseball to look at, and while nothing’s changed about the past, there have been some shifts in the present. Chris Owings is looking like the long-term answer (for now) at shortstop and while he’s not Gregorius with the glove, he profiles to be adequate at worst with a chance to be average. An average fielding shortstop who hits consistently and has a little pop is surely an asset. There’s no reason to think that Owings can’t be a 2-win player if he’s the full time starter and according to FanGraphs, there were only 11 of those in all of baseball last year.

Owings, of course, isn’t the real worry when it comes to changes. That fully belongs to Mark Trumbo, who is shifting to the outfield after playing either first base or DH almost exclusively for the Angels over the last few seasons. The only exception is 2012 when he logged over 700 innings in the outfield. The results were uninspiring to say the least, although left field appears to have treated him more fairly than right field did.

You know all of this and it’s been said 1000 times, so let’s just get to the point. I’ve heard a lot of banter about how Trumbo should be given more time to “learn the position” and that “he’ll improve” over the course of the season. I’m not buying it. First of all, he’s already learned the position. Trumbo has logged over 1000 inning in the outfield over four seasons. The fact that he hasn’t logged more should tell us something: he’s not meant to be there in the first place. Maybe he can improve over plays like this, but his limitations aren’t due to experience, they’re due to athleticism and a lacking natural aptitude for the outfield. Of course, none of this is Mark Trumbo’s fault and my critique isn’t personal, the outfield just isn’t the best fit for him. But his lack of defensive prowess will cost the Diamondbacks this year, and that’s on the man that acquired him.

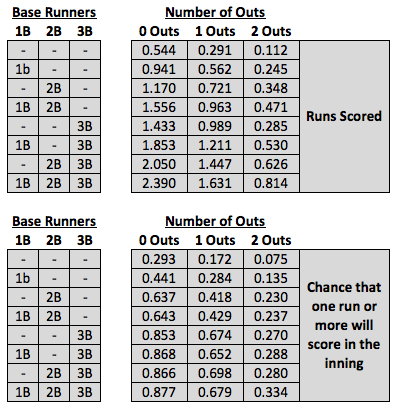

I want to point to is just how his defense will cost Arizona going forward in 2014. To do this, I’d like to use a concept that is well accepted and oft-cited in the sabermetric community: run expectancy. Usually shown in a table, run expectancy tells us the average number of runs that score in the remainder of an inning in each of 24 base-out states, such as runner on first, two outs, bases empty, one out or bases loaded, no outs, for example (yes, there are 24 combinations of bases/outs). Since baseball has been played for a long time and there are a ton of games and innings, we’ve been able to calculate the expected number of runs that will score, or the frequency that a run will score, in any given situation. For example, runners on first and third with no one out will, on average, result in 1.853 runs scored in that inning. This is why we get excited when an inning starts this way since we have learned that this often leads to multiple runs scored.

So before we speak specifically on Trumbo’s defense, take a minute to review the following run expectancy tables, which have been compiled from 1993-2010, courtesy of Tom Tango:

*Note: if you read no further, do yourself a favor and purchase a copy of The Book. Its figures and strategies have already and will continue to shape the game of baseball as we know it.

I know what you’re thinking: what the hell do these tables have to do with Trumbo’s defense? That’s a great question and one that I’ll attempt to answer. Let’s run through a couple of scenarios and see how they would impact the team.

- Bases empty, no outs (.544 runs scored on average). Leadoff hitter hits a shallow fly to left that drops right in front of a charging Trumbo. Let’s presume, for the sake of the exercise, that the average left fielder makes the catch but that in Trumbo’s case, it falls in for a single. Rather than having bases empty, one out (.291 runs scored on average) we are left with a runner on first and no outs (.941 runs scored on average). Needless to say, that’s a pretty big change and leads to over a half a run scored on average had the ball been caught for the out.

- Runner on first, two outs (.245 runs scored on average). The batter lines a ball into the gap and Trumbo is one step short of making the catch on the run. Instead, the ball rolls to the fence, the runner from first scores and the batter ends up on second. Instead of ending the inning, we have a run plated and are left with a runner on second, two outs (.348 runs scored on average). This is obviously damaging as a run has scored and the opposing team is now in a better position to score (again) than they were before the missed catch.

- Bases empty, one out. The batter lines a ball over the third baseman’s head and rolls down the line. Trumbo is slow getting over and can’t cut the ball off, allowing it to roll to the fence. In this scenario, the average left fielder could have cut it off and held the hitter to a single (.284 runs scored on average). Instead, he ends up on second base (.418 runs scored on average). Just misplaying the ball down the line significantly changes the number of runs scored on average in the inning.

The point of all of this is to show that misplays on defense add up in a tangible, trackable way. We don’t have to guess at what the change in outcome is, we can calculate it game-to-game and over the course of the season.

The other point of this is to show that Trumbo is going to have to do real damage with the bat to overcome the tangible losses in the field. A solo homer is nice, but letting a ball drop in the gap that would have otherwise been caught can be just as devastating depending on the current base/out state. If Trumbo has a career year at the plate, then no one is going to give pause to his defense. But if he puts up another 106 wRC+ season and the defense is still lacking, the team may need to seek alternative solutions. Remember, the goal isn’t to score more runs than last year, the goal is to score more runs than your opponent during each game. Trumbo may or may not be the best way to accomplish this. We simply haven’t seen enough of his offense to know this yet.

Obviously, the other choice in left is a healthy Cody Ross, something we don’t have at the moment. He should be ready to go in relatively short order, however, and clearly rates as a better left fielder than Trumbo does. That should be expected as he’s more agile, faster and has an adequate arm. He’s also made a career out of running around out there rather than attached to first base, a comparative vote of confidence in his outfield prowess. But can Ross really run down more balls in the gap than Trumbo, and if so, how many? Can Ross really get to that ball down the line that Trumbo couldn’t? Is Ross going to snag that sinking liner that Trumbo took on a hop? I don’t know, but someone else, someone who gets paid to make decisions about a major league roster, had better have a solid answer, because as the tables and scenarios above illustrate, the outcomes add up.

All of this isn’t to bag on Mark Trumbo, who by all accounts is a fantastic teammate. It’s instead intended to show that defense isn’t some abstract talking point to denigrate the decisions of Kevin Towers, but rather a quantifiable practice. We know that there will be struggles in left field as long as Trumbo is the primary player there because there’s a track record of it. Don’t hope for him to morph into a player he’s not. Rather, hope for more #trumbombs than #trumbones so the #Dbacks can #slaphands on a regular basis.

6 Responses to Speaking of Defense In Left Field…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Starting 2022 with a frigid dog walk sounds just lovely https://t.co/xoLZSZBpGp, Jan 01

Starting 2022 with a frigid dog walk sounds just lovely https://t.co/xoLZSZBpGp, Jan 01 I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30

I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30 Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29

Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29 Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27

Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27 Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Powered by: Web Designers

Just a hypothetical scenario: do you ever think Goldy could shift to third and play Trumbo at first in the next few years? And Prado out in left field? Would that be a better defensive alignment (assuming Goldy could learn third, like he learns everything else)?

Of course, I’m basing it on what the Tigers did (which they recently undid).

Third base is far more valuable than first, defensively speaking, so if Goldy could hack it, he’d be over there in the first place. The only reason to even imagine it is for the same reason the Tigers tried it: because you have another hitter that’s of similar caliber that needs to play first. There isn’t a first baseman that’s available and affordable that justifies Goldy trying to play third, and Trumbo’s definitely not that guy. Creative exercise, but not one that fits in reality, which I think you already alluded to.

That makes sense. As much as I dislike Prince Fielder, I suppose Trumbo isn’t really near him in terms of offensive value.

Reminds me of the Kubel signing and everyone screaming that he couldn’t play left field… all he did was lead the NL in OF assists.

But there’s more to defense than outfield assists. His range was lacking, that’s for sure, and they only ran on him because he was a liability in the first place. He made the play, obviously, but he clearly wasn’t respected as a fielder.