Evaluating Kirk Gibson with Sabermetrics

Let’s get one thing straight right off the bat: no one, and I mean no one, thinks a manager can be evaluated solely with sabermetrics. The game is played on the field, and while General Managers can at least be evaluated primarily on their transactions, there is a ton to the manager’s job that defies statistics and always will.

We also don’t know how much those non-measurable attributes are important, which is another way of saying: we can’t ever be certain about how important or definitive the measurable things are. With that caveat, though, there are still some ways we can take a look at Kirk Gibson‘s performance.

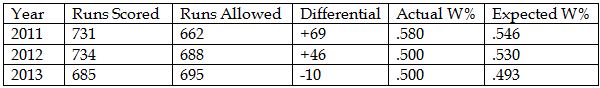

Expected record is one of those ways. Let’s start with the simple version, applying runs scored and runs allowed to determine how many games the D-backs should have won during the three full seasons of Kirk Gibson’s tenure.

The D-backs overperformed in 2011 by a significant margin, in 2013 by a tiny margin, and underperformed in 2012 by a healthy margin. That looks a lot like chance, and it probably is. And we can do better.

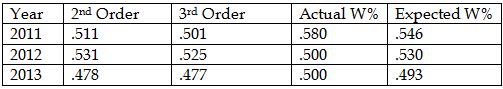

Baseball Prospectus runs “2nd Order” and “3rd Order” expected winning percentages — instead of calculating how many wins a team might be expected to have given a certain number of runs scored and allowed, these numbers dig deeper to look at how many runs a team should have been expected to score or allow, before turning that into expected wins. Here’s how Gibson’s teams looked through that lens (I’m keeping “Expected Wins” from the first table there for comparison):

The “2nd Order” winning percentages are based on expected runs scored, calculated by counting up all of the events that help create runs — walks, doubles, stolen bases, etc. — and randomizing sequence and outcome. “3rd Order” goes a step further to put these events in a vacuum, by adjusting “2nd Order” for strength of schedule. Over a season, strength of schedule does tend to even out — but it’s definitely possible to get some good or bad luck based on the opponents’ turns in the starting rotation and timing of key injuries.

Comparing “3rd Order” winning percentage to the D-backs’ actual record casts Gibson’s tenure in a very favorable light. The significant overperformance in 2011 goes through the roof with this method, while the slight overperformance from 2013 grows and the underperformance from 2012 shrinks. In Gibson’s three full years, his teams have had a winning percentage .026 greater than expected, on average. That’s four wins per season, albeit largely on the back of the incredible 2011 run.

You can tell me to ignore 2011, or that this discrepancy isn’t as meaningful as it may appear. To be honest, I have no idea how much confidence to put in it. But if Kirk Gibson were a bad manager, we might expect “3rd Order” winning percentage to be greater than actual winning percentage, and here it trends significantly in the opposite direction — enough to get the benefit of the doubt in my book.

While the young 2014 season has been an unmitigated disaster thus far, the sample is so miniscule that we really can’t draw any conclusions about the team’s true talent level — which means we certainly can’t draw any conclusions from runs scored/allowed about Gibson. But for what it’s worth, it doesn’t seem to be Gibson. Remember the run differentials from above for the last three years? The D-backs’ current run differential for this season is -48.

The D-backs’ “3rd Order” expected winning percentage for this season is .321, a step up from the team’s actual winning percentage of .222. But in a sample of just 18 games, that difference in winning percentage comes out to just 1.8 games or so.

Again, expected winning percentage is not a good way to evaluate a manager, it’s just some small piece of evidence that can be used in the analysis. Plenty of the off-field, communication, and big-picture considerations are important, even if we don’t know how important. And as Jeff detailed yesterday, Gibson had an integral role in bringing a flawed vision shared with GM Kevin Towers to life — that does not reflect on him well.

. . .

There are other aspects of a manager’s performance that we can evaluate with sabermetrics. An example is stolen bases — both the number of attempts, and the success rate for those attempts. Does Kirk Gibson do the running? Of course not. But if a player were particularly bad at stealing bases (cough, Parra, cough), a manager absolutely can put up the stop sign. Gibson… hasn’t done that. Toward the beginning of his tenure, the D-backs were almost league average in stolen base percentage (71%, compared to league average 72%). But while the league average success rate hasn’t really changed, the D-backs’ has. In 2012, the team’s rate dipped to 65%. In 2013, it was the worst rate in the majors, 60%.

Another thing that can be measured is lineup construction, a fluid endeavor that, in extreme examples, can make the difference for fifteen runs or so (about a win and a half). Bunt habits, creative use of platoons and bullpens, and timing and frequency of intentional walks are also things a manager can control that are measurable.

Inspired by Russell A. Carleton of Baseball Prospectus and his recent piece “Baseball Therapy: Why Sabermetrics Needs Translational Research,” I’d like to announce that we will be looking at some of these measurable things in a new series called “Reasonable Demands,” which will examine a particular aspect of in-game strategy and recommend small changes for the better. In so doing, we will keep a close eye on how Kirk Gibson has actually performed according to those metrics, so stay tuned. I have done some of the research already, however, and so I can say — he’s been better than you probably think, notwithstanding the team’s lack of success in stolen bases. Kirk Gibson may only be a good manager so long as he continues to have the commitment of the organization and the respect of the players, but it might be good for the team if he does.

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04 RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

RT @JCGonzalezOR: Special thanks to @HillsboroHops for hosting a LatinX community outreach and visioning session. This organization i… https://t.co/OxmEgwOpEh, 22 hours ago

RT @JCGonzalezOR: Special thanks to @HillsboroHops for hosting a LatinX community outreach and visioning session. This organization i… https://t.co/OxmEgwOpEh, 22 hours ago Old friend alert https://t.co/xwSHU0F8Hn, Dec 08

Old friend alert https://t.co/xwSHU0F8Hn, Dec 08 Every once in a while you get a beer that's just a little off... Usually happens to me at airports., Dec 07

Every once in a while you get a beer that's just a little off... Usually happens to me at airports., Dec 07 If Pollock doesn’t sign with a team that wears red uniforms I’m going to be really disappointed. Working theory: Se… https://t.co/zHn9DqzEiD, Dec 07

If Pollock doesn’t sign with a team that wears red uniforms I’m going to be really disappointed. Working theory: Se… https://t.co/zHn9DqzEiD, Dec 07 The work here by @Britt_Ghiroli is splendid https://t.co/c8tSq0vw3T, Dec 07

The work here by @Britt_Ghiroli is splendid https://t.co/c8tSq0vw3T, Dec 07

Powered by: Web Designers