The Same Old Beef

Before Welington “Beef” Castillo came along, the Diamondbacks’ catching situation was laughably bad. It inspired a number of articles that all came to the same general conclusion: they aren’t actually going to run that out there all season are they? They were, and then the Mariners did a dumb thing (as they are seemingly prone to doing) and took Mark Trumbo off of Arizona’s hands along with swingman Vidal Nuno for Castillo, Gabby Guerrero and Jack Reinheimer. For inquiring minds who missed our winter prospect coverage, Guerrero is intriguing and has a chance to be a good big league player but needs significant work while Reinheimer looks to be a strong candidate to have a long career as MLB utility infielder. While those are nice and potentially useful gets for the organization, Welington Castillo was the key and part of the move and it paid off brilliantly over the remainder of 2015.

Even though it’s been said in this space before, it bears repeating that Castillo is a really poor catcher. He’s proven to be a productive hitter for being a catcher, but the bar there is obviously pretty low (and especially low for Arizona given their options). Catching is the most physically demanding job in baseball for a position player, so I think we have to acknowledge the difficulty associated, but nonetheless, Castillo stacks up very poorly compared to his contemporaries and even those throughout history. We know this because, on Tuesday, Baseball Prospectus dropped a whole load of new defensive data for catchers on us (#Catchella). Of 5,324 minor and major league catchers dating back decades, Welington Castillo sits in 5,296th place. He’s in the 99th percentile as a catcher, defensively, for his career. That’s bad.

You might be wondering what’s included here. I have an answer from those who created the stats, Jonathan Judge and Harry Pavlidis:

The statistics both apply to and measure players other than catchers, but they are all perhaps most important to catchers as we measure their total value to a team. The statistics are four-fold, covering three critical catching skills:

1. Running Game

a. Swipe Rate Above Average (SRAA) – the effect of the player on base-stealing success;

b. Takeoff Rate Above Average (TRAA) – the effect of the player on base-stealing attempts;

2. Blocking Pitches

a. Errant Pitches Above Average (EPAA) – the effect of the player on wild pitches and passed balls;

3. Framing (AKA “Presenting”)

a. Called Strikes Above Average (CSAA) – the effect of the player on strikes being called.

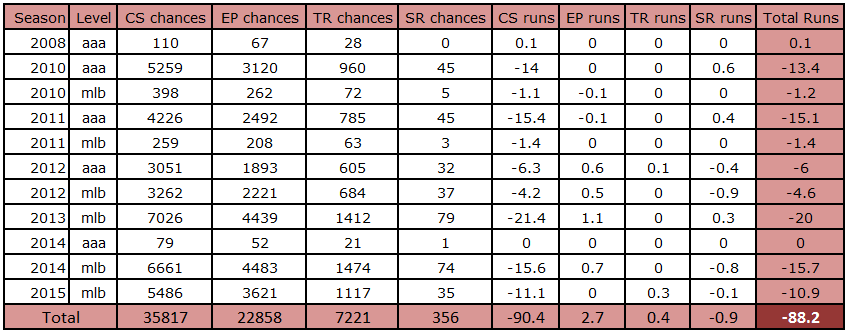

This seems to cover the list of “important things a catcher does” pretty well. The only missing ingredient is pitch sequencing and that was basically modeled once before it got Robert Arthur hired by the Astros. Given all that we’re left with, Castillo does look pretty terrible. Here’s how his career has stacked up with these newly-available (but widely-accepted) stats, first in terms of opportunities, then converted into run values:

*Based on AAA and MLB time only *Click to enlarge

Surrendering 88 runs of value is a lot to hemorrhage. In total, Welington Castillo has given up something like 9 wins through is defense alone over this span. Of course, he hits, too. During that time, he’s responsible for 274 runs through weighted-runs created, but those 88 runs he’s given away surely chip into what he’s achieved offensively. It’s fine to be a bat-first catcher so long as the defense isn’t tragically far behind. In this case, the defense sort of is and his offensive track record has been somewhat unstable. There’s a reason why Seattle was willing to trade him and start Mike Zunino, after all.

And, if we’re really zeroing in here, calling Castillo a poor defensive catcher might not be the best description we can come up with. In terms of controlling runners, he’s been effectively neutral. Same goes for blocking pitches. But Castillo (and his pitchers) absolutely takes it in the teeth when it comes to framing pitches. He’s just been really, really bad. Like Jarrod Saltalamacchia, Brandon Inge, Mike Napoli bad.

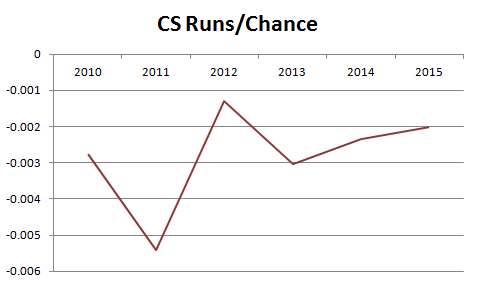

But if you want a silver lining here, it’s this: Castillo has been improving. True, you really have to squint to see it, but it’s in there if you look hard enough. If we take a peek at Castillo’s Called Strike Runs Above Average (framing) compared to his number of opportunities, we see this during his MLB stints:

Yes, the values are all negative, but they’re getting closer to zero, which would be “average.” He’s still a modest distance away from that mark, but he did a nice job in something like a half season in 2012, then dipped in 2013, only to slowly rebound in 2014 and 2015. As Castillo has aged and caught more pitches, he’s gotten better. He’s still not good, but he’s getting somewhat less bad. This isn’t dissimilar to what Eno Sarris noticed as it pertained to Chris Iannetta who has improved throughout his career as a receiver of pitchers. It might be that as Castillo gains experience behind the dish, and as teams (hopefully the Diamondbacks included) start to learn the value of framing pitches, he can really turn around his reputation as an extremely poor pitch framer. That transformation might only move him from “extremely poor” to “poor,” but at this point that’s a clear victory.

I don’t know what the D-backs are telling Welington Castillo in their player meetings. I don’t know what kinds of goals he’ll set with them before the season. But I do know where I’d put my emphasis if I were them and I do know where I’d focus my instruction: pitch framing. Castillo has been bad at an historic level in this department, but improvement here is a two-fold gain – his pitchers will surely enjoy the fruits of his labor. Better pitch framers keep pitch counts down for their pitchers and help make more successful pitchers overall. If the team lacks the resources to help Castillo on their own, they need to find him some help. It’s abundantly clear that he, and the team, could drastically use an improvement here, even if it’s a relatively small one.

6 Responses to The Same Old Beef

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04 RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

This Suns matchup comes at a good time for my hometown Blazers #RipCity https://t.co/fQ45wdfQUk, 24 mins ago

This Suns matchup comes at a good time for my hometown Blazers #RipCity https://t.co/fQ45wdfQUk, 24 mins ago RT @ZHBuchanan: Our @Ken_Rosenthal spoke to Ken Kendrick about trading Paul Goldschmidt.

https://t.co/O5fHRlyBxD, 7 hours ago

RT @ZHBuchanan: Our @Ken_Rosenthal spoke to Ken Kendrick about trading Paul Goldschmidt.

https://t.co/O5fHRlyBxD, 7 hours ago RT @CardsNation247: We have a good show lined up for tonight. Leading off is our friend of the show @buffa82 followed by Jeff Wiser… https://t.co/eltZC0uvyg, 7 hours ago

RT @CardsNation247: We have a good show lined up for tonight. Leading off is our friend of the show @buffa82 followed by Jeff Wiser… https://t.co/eltZC0uvyg, 7 hours ago RT @juanctoribio: To piggyback off the @ZHBuchanan and @OutfieldGrass24 that the #Rays were involved in the Paul Goldschmidt sweepsta… https://t.co/spg9x7X1L5, 7 hours ago

RT @juanctoribio: To piggyback off the @ZHBuchanan and @OutfieldGrass24 that the #Rays were involved in the Paul Goldschmidt sweepsta… https://t.co/spg9x7X1L5, 7 hours ago RT @OJCarrascoTwo: Read this from the world famous, @OutfieldGrass24 https://t.co/cHUie1I5Le, 7 hours ago

RT @OJCarrascoTwo: Read this from the world famous, @OutfieldGrass24 https://t.co/cHUie1I5Le, 7 hours ago

Powered by: Web Designers

The concern with Beef is that he had a negative effect on last year’s staff because of those negative metrics, and he will have a negative effect on this year’s staff and thereby negate the staff improvements. Are there any stats on clubs that went from a positive to a negative contributor behind the plate, as to what impact they had on the staff?

One place you could check, and the one that most obviously comes to mind, is the change for the 2012 and 2013 Pittsburgh Pirates. They went from terrible behind the plate to very strong with the addition of Russell Martin. You can look at things like K’s and BB’s, but you can also look at things like pitches per inning, average innings per start, etc. If you wanted to see what happened to a staff (and they didn’t retain every pitcher that offseason, but they kept a few) with by adding a good framer, that’d be my first stop. I recommended it below, but Big Data Baseball by Travis Sawchick outlines this from the Pirates’ perspective and they were all aboard pitch framing early on.

Doh!

You can talk about being Mike Napoli and Jarrod Saltalamachia bad all you want, but both Salty’s and Napoli’s teams went to the World Series with them behind the plate.

I’m not buying this….. especially on catcher framing. I firmly believe this is the most over-analyzed stat in baseball.

If framing is so important, how did Salty and Napoli make it to the World Series being the worst framers in baseball.

Let me put this one another way: why was Mike Napoli moved out from behind the plate? Why did he only play parts of four seasons at catcher, never starting more than 84 games in one season as a catcher? That’s not to be argumentative, but there’s a reason they limited his time back there and made him a first baseman. If they could have been getting 130 wRC+ from behind the plate throughout his career, every team would have done that because that’s insanely valuable.

I think catcher framing is a hard thing for a lot of folks to accept, but the bottom line is that most baseball teams already have. It’s the same for those who don’t like WAR to measure production or wOBA to measure offense. You don’t have to like it, but the game has accepted and moved on with it, using it to guide and make decisions. I have a source who worked for an AL West club last year and they taught framing to their minor league catchers. Framing clearly falls into this mold as an abstract, yet accepted principle.

For a great look at it, and maybe it will or won’t sway you, check out Big Data Baseball that came out about a year ago. It details the Pirates and their work with Russell Martin and Francisco Cervelli. It’s a really great read no matter what you think of pitch framing.

[…] little more than a week ago I told you that Welington Castillo is a bad pitch framer. He’s more or less average at the other, more traditional parts of catching – namely blocking […]