What the D-backs Can Learn From the Rest of the West

The NL West is an odd place. Home to the majors’ two most offense-friendly environs and its two most pitcher-friendly parks, it’s also got Dodger Stadium for variety. Thanks in large part to the unbalanced schedule, navigating the division successfully is paramount for the teams that call it home, including the D-backs. Despite the differences, the division’s parks all have particularly large outfields, meaning some things stay consistent throughout; still, other player qualities work out completely differently depending on whether home runs play up or down. Distinguishing between those two flavors can mean mastering the NL West, and for the D-backs, mastering the West could mean mastering the National League.

A couple weeks back, we looked for some takeaways from the Rockies’ experiences, since they’re the team in the situation most similar to that of the D-backs. And last week, we scoured the Giants’ experiences, as they appear to be the only team to master the division in recent memory, and really since Chase Field f/k/a Bank One Ballpark made Coors Field less of an outlier. Like the Padres, the D-backs seem not to have profited from other NL West teams’ experiences. Let’s put the Rockies and Giants lessons in terms more directly applicable to the Diamondbacks — for more specifics underpinning these conclusions, jump back to those posts and their clearly-marked lessons.

Lessons Consistent Throughout the Division

Fielding. The effect of having a large outfield on outfield batted balls that are not home runs. Pretend for a second that the NL West parks added some foul territory on the sides to what is currently fair. The corner outfielders would have to stand farther apart. There’d be more room for hits to fall in — probably in between the corner outfielders and the new “foul” lines, but also between the corner outfielders and the center fielder. A ball hit in the air with a smallish hang time — call it two seconds — is suddenly much more likely to find an open area to land in, unmolested by a fielder. This is really no different than having outfields that are no wider, but are deeper. Fielders still end up standing a little farther apart, but that’s by virtue of needing to move back away from the infield more. Moving away from the infield, outfielders are still farther away from the outfield wall than they would be in a smaller park, but there’s still more space in front of them for a dying quail to die a more noble death.

A big part of this is overlap. So long as it doesn’t fly over the fence, a ball with a 4.5 second hang time almost definitely will be caught. By the same token, fly balls with long hang times can frequently be caught by more than one fielder. That’s a waste; it’s inefficient. Since most fly balls don’t hang in the air that long, that inefficiency is something that teams have to learn to live with, unless, say, Tyler Clippard is on the mound. The way that overlap comes into play is that in a large outfield, there is less overlap. A ball with a 4.5 second hang time by the wall in left center will still almost definitely be caught, but what about 4 seconds? 3.5 seconds? In a small ballpark, it’s still possible that two outfielders would get there in time, even if they aren’t particularly good at outfielding.

In a large NL West ballpark (or Kauffman Stadium, say), it’s less possible that two outfielders would get there in time. Suddenly, if the left and center fielders have more range, they can accomplish more things than a couple of crappy outfielders would. There’s less inefficiency. An outfielder with great range simply has more opportunities to make out-of-zone plays. On the flip side, less overlap means below-average fielders will get exposed more often; there are more batted balls that only one outfielder of average quality could reach in time, which means there are more batted balls that won’t get caught on the fly by outfielders with below-average range. We’ve referred to outfield defense being “magnified” in the large outfields of the NL West. Good defense out there helps you more; poor defense hurts you more.

Hitting. More outfield real estate can mean more hits, but that progression doesn’t follow a straight line. Picture a tiny ballpark with a hilariously shallow outfield wall, such that the outfielders almost never run anywhere; they saunter. If the outfield fence is also short, just about any outfield fly ball would be a home run; through home runs only, hitters’ batting averages would skyrocket. Can’t field those. At the same time, though, hitters’ rates of singles and doubles would fall off the table, and triples in that park would be next to impossible.

Now picture a field that has no outfield wall; to hit a home run, you’d need to hit an “inside” the park homer, hitting it so far that you can round third before an outfielder can get the ball to the cutoff man. Without a wall to stop line drives that go through the gaps, hits that were doubles would be triples almost all the time. Outfielders would make position adjustments constantly and drastically depending on the strength of the hitter, mostly toward the infield or away from it. Wherever they went, they’d leave some fertile territory for fly balls to fall in their wake. Overall, the outfielders would probably play more deeply than in a walled stadium, leaving gobs of grass in front of them — drastically more singles. Home runs would be reduced, but they’d still happen. Offenses’ total bases would skyrocket, but their batting average would also be obscene. Fewer fly balls would get caught. Putting it in terms we used earlier: outfielders’ territories would be so much bigger than far less of their zones would overlap on fly balls with long hang times.

The hitting lesson consistent across the NL West is that big outfields reward singles hitters who dump the ball in front of outfielders, but also gap hitters who can push the ball in between outfielders. It’s not so much about getting the ball over fielders’ heads more often than in smaller parks, although there’s definitely some of that, too. Less consistent in the division is a large outfield’s effect on home run type batted balls, but singles and gap hitters play up all across the NL West — the key is that you have to actually hit it out of the outfield regularly. Infielders play at the depth they need to play at in order to get the ball to first base on time. They don’t move back to help cover the outfield. At some point, the fields of the NL West diverge — high fly balls play differently depending on whether you play in an average large park like PetCo and AT&T, or the bizarre situations at Coors and Chase. In that sweet spot between 10 and 30 degrees, though, all NL West parks play up. To take advantage as a hitter, a consistent launch angle skill is especially helpful — and a consistent exit velocity skill can be especially ineffective.

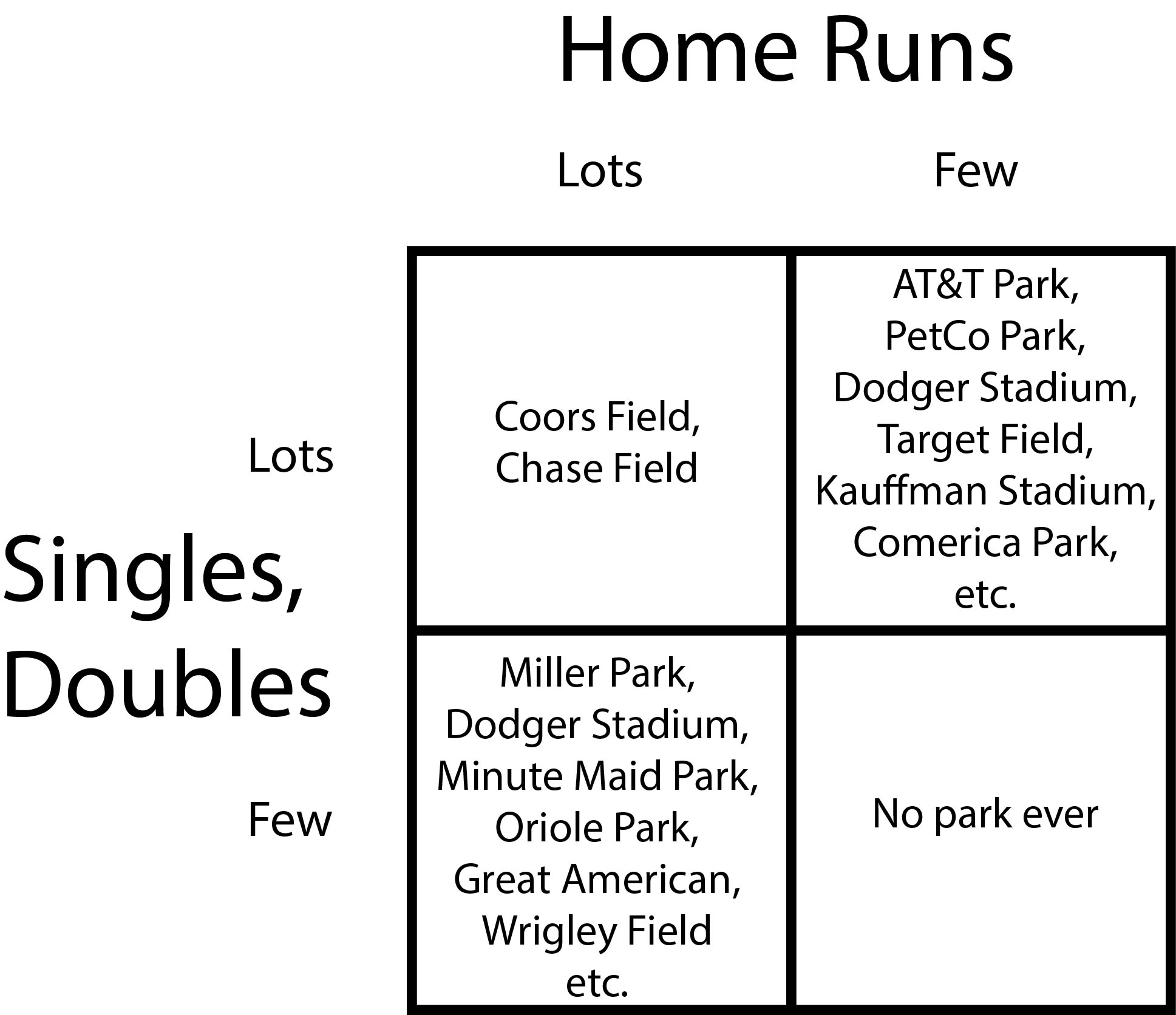

Pitching. Hitters want to put the ball in the outfield to benefit most from the large outfields of the NL West. Conversely, pitchers want to avoid that to the maximum extent possible. There are two ways to do that: prevent hitters from putting the ball in play at all via strikeouts, or have a big-time ground ball percentage that cuts not only into fly balls, but specifically into “fliners” and soft line drives. It’s not that a high K rate or a high ground ball rate plays better in the NL West than it does elsewhere; it’s that those are the types of profiles that are most resistant to those large outfields. In the graphic above, all NL West parks are above the middle line. That’s what they have in common.

Pitching. Hitters want to put the ball in the outfield to benefit most from the large outfields of the NL West. Conversely, pitchers want to avoid that to the maximum extent possible. There are two ways to do that: prevent hitters from putting the ball in play at all via strikeouts, or have a big-time ground ball percentage that cuts not only into fly balls, but specifically into “fliners” and soft line drives. It’s not that a high K rate or a high ground ball rate plays better in the NL West than it does elsewhere; it’s that those are the types of profiles that are most resistant to those large outfields. In the graphic above, all NL West parks are above the middle line. That’s what they have in common.

There might be one other thin band of pitchers who can be successful in the NL West: fly ball pitchers so extreme that their average hang times on fly balls is greater than most. At that point, it’s like the outfield becomes artificially smaller; fielders’ effective zones become bigger, on average, and fielders get back to those overlap points more often. You have to be pretty extreme to accomplish that, but we saw Matt Cain do it for several consecutive years, and it’s part of what’s made Kenley Jansen so successful. Tyler Clippard might balance on the edge of a knife, there. It’s a smaller group of pitchers than high-K or high-GB pitchers, but on the other hand — the few FB guys that can benefit like this are not just resistant to the environs of the NL West; they actually benefit from them, but less so at Chase and not at all at Coors.

Lessons Applicable Only to Rockies, D-backs

That graphic above really shouldn’t be boxes. 28 ballparks fall more or less on a straight line from the bottom left to the top right, with some minor variations like Fenway, which boosts doubles a ton but not singles. Coors Field and Chase Field are like nothing baseball had ever seen before. In those parks, it’s like playing baseball on a different planet. In those parks, the math of baseball is all wrong. It really shouldn’t be the case that a park can encourage singles, doubles, triples, and home runs, but that’s what Coors Field is. Chase Field is not as extreme, but it manages to boost inside-the-park hits while staying neutral or slightly positive on home runs. And that’s just weird.

With the exception of high-FB pitchers, everything we talked about above still applies to these two parks, because they have very large outfields. There’s still more space between fielders, although greater batted ball distance (relative to exit velocity) slightly mitigates the outfield dimensions’ propensity to reduce overlap between outfielders (longer hang times makes for more overlap). At Coors and Chase, however, we add another layer. The effect on outfielders in terms of fielding is almost non-existent; defense is still “magnified,” and the fact that slightly more batted balls become home runs only mitigates that a tiny bit. In terms of hitting, more than one style plays up. And in terms of pitching, the consequences of failing to keep the ball out of the outfield are tremendous.

Few hitters benefited from Coors Field more than Todd Helton, who once made a credible run at .400 before sputtering to a lowly .372 average in 2000. The only real difference between Helton and Paul Goldschmidt: Helton had a much higher contact rate, striking out just 12.4% of the time in his career. Helton hit over 40 blasts twice, and 30 or more another four times. More remarkable were Helton’s double totals; between 1998 and 2007 (10 seasons), he averaged over 45 doubles. When he hit 42 home runs, he added 59 doubles. When he hit his career-high 49 long balls, he still hit 54 two-baggers. He was a gap hitter and a home run hitter. Can you think of anyone better suited to Coors Field than that?

If you’re the Rockies, you always have a safe play in the outfield: get good defenders who hit the ball in the outfield consistently, any part of the outfield. Corey Dickerson, Ryan Spilborghs, Charlie Blackmon, and even Gerardo Parra — those guys are worth something to any team, because they’re starting-caliber players. To the Rockies, though, they will always play up, and they’re not a particularly expensive type of player. If you’re looking to capitalize even more, however, you want hitters who don’t just hit the ball in the gap, but who can hit the wall in those gaps consistently. If they “miss” under the ball, they’ve hit a home run. If they miss over the ball — they still have a pretty great chance at a double. If they get the launch angle right but don’t sweet spot the ball, exit velo may suffer — and they end up with a Texas Leaguer single. Carlos Gonzalez can’t lose. A.J. Pollock would have been a god-like figure wearing purple.

At Chase Field, the value of a hitter like Todd Helton may not be quite as extreme, but the value of hitters who aim for lineouts to center field like Jake Lamb is still enormous. Goldy and Lamb regularly commit a Chase Field no-no — they have high strikeout rates. What they lose in singles and doubles, however, they gain back in home runs. If they called AT&T Park home, their stat lines might look a lot more like those of Brandon Belt.

D-backs Takeaways

I’m just one man looking at information one way, but it seems that roster decisions have a much larger impact for the Diamondbacks than they might for other teams. If you’re a team with a very “normal” home park in a very “normal” division, like, say, the Nationals, any decent major leaguer could have a role to play. More of a bat than a glove? Fine; if they’d even out in general, they’d even out for you. Fantastic glove man who scrapes by above the Mendoza Line? That’ll work too. We’re used to that kind of balance. But Chase Field isn’t balanced.

For the D-backs, power is great, but it should be the line drive kind of power. Otherwise, contact rate wins the day. A glove-first guy like Nick Ahmed would be fine, if that player did something to benefit from Chase Field, which is so giving to so many players. The only way to really fail to capitalize on Chase Field is to have a poor contact rate with no power at all. No power is perfectly fine, but as we saw with Ender Inciarte, a glove-first guy looks like a bat-not-far-behind guy in the NL West if he can take advantage of the outfield with some contact skills. Maybe Chris Owings is getting there.

The heavy preference for contact skills can and should extent to hitters with power that plays everywhere; to the extent they’ve sacrificed some contact for greater power, all they’ve done is cheat themselves. Remember, Chase Field doesn’t have a very positive home run factor. More power does mean home runs, but not more so at Chase than at other parks — and yet by failing to make more contact, hitters like that rob themselves of the benefits of Chase Field’s cavernous outfield. Mark Trumbo has been money with Baltimore this year, in a tiny outfield. Peter O’Brien might be able to do the same. But as we’ve seen with Yasmany Tomas, a one-dimensional power bat is typically a bust for the D-backs. Like in any other park in the NL West (and largely because this is also true for the other parks in the NL West), Chase magnifies the defensive characteristics of outfielders. If a fairly poor outfielder is anything less than a great fit with Chase Field at the plate, then regardless of how good he is, he’s probably worth more to some other team.

Good or bad, a pitcher that succeeds primarily through contact management is unlikely to fare better with the D-backs than he is with another team, unless that contact happens to be largely of the ground ball variety. Good or bad, an outfielder that has very good range is likely to have more value for the D-backs than he does for most other teams. Good or bad, high strikeout rates from a hitter is likely to mean that hitter won’t benefit from Chase Field as much as the competition does.

These same things happen to hold true for all NL West teams; it’s just the Goldy/Lamb hitting profile wrinkle that makes the D-backs different from the Giants and Padres, the rules have bigger consequences for the Rockies, and the rules are less important for the Dodgers. They’re not far apart, which is a big part of why those rules are so much more important than they would be for a team with a similar home park but different division, like the Royals and Kauffman Stadium. And so the Padres give us the most salient cautionary tale of all, most likely.

It’s hard to manufacture a contention window, the way the Padres attempted to do before the 2015 season. Maybe it’s not possible. But it’s sure as hell not possible if you target the wrong types of players, players who don’t play up in the NL West, but also play down. Wil Myers isn’t a center fielder, and Matt Kemp is no longer the defensive asset he once was. James Shields is a contact management pitcher, and when he strained to try to keep the ball from going in play, he did manage to increase strikeouts — and yet still did worse overall than in his previous four seasons. Shields should have worked, considering he did so well with the Royals — but while the Royals have played a Giants brand of roster construction with excellent defensive outfielders, Shields got Kemp (-18 UZR/150), Justin Upton (2.8 UZR/150), and a smattering of decent to terrible work from center fielders (Melvin Upton, Jr. 6.5 UZR/150; Will Venable -0.3 UZR/150; Myers -42.5 UZR/150). Overall, Shields had an outfield behind him that was mediocre, but not horrific. But the NL West magnifies the defensive characteristics of outfielders.

It comes down to the right players. It seems pretty clear now why A.J. Pollock was such an incredible force for the D-backs last year; his defensive excellence was magnified, but he brought a brand a contact hitting to the team that also meant extra bases and even home runs, similar but not the same as Goldy or Lamb. Pollock is tremendously missed. Pollock, however, has not been the difference between a playoff-bound team this season and the club with the 36-43 record before us now. There are players on the Active Roster and also the 40-man that don’t fit the “rules”: Tomas, O’Brien, Ahmed, Welington Castillo, Chris Herrmann, Gabriel Guerrero, Randall Delgado, Dominic Leone, possibly Shelby Miller and Silvino Bracho. Replacing those players with players of similar quality who happen to fit Chase and the NL West a lot better could make the difference in the team’s retooling effort.

2 Responses to What the D-backs Can Learn From the Rest of the West

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30

I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30 Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29

Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29 Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27

Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27 Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26 Feeling cute might delete https://t.co/NyqGSXVOwQ, Dec 25

Feeling cute might delete https://t.co/NyqGSXVOwQ, Dec 25

Powered by: Web Designers

This is really tremendously good stuff. I have learned a lot. Thanks so much. From your fingers to TLR’s ears!

I’m back after a long absence. This nightmare of a season forced me underground. But this is really well done and well researched. Too bad the FO is too incompetent to put this into practice.