D-backs and Run Scoring Efficiency

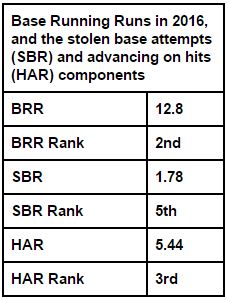

In recent history, the D-backs’ penchant for taking extra bases seems to have them at or near the top of many base running leaderboards. As of this writing, the team is second in Baseball Prospectus’s Base Running Runs, trailing only San Diego, and last year, the D-backs finished third. It’s not like they’ve always been the NL’s top team in this regard, but in the last three seasons, the team’s high marks have not been powered by stolen bases — they’ve been powered by advances on batted-ball plays, like ground outs, air outs, and (especially) hits.

Fresh off some new examples in the first two Mets games this week, it’s easy to see why Chase Field has such a high park factor for triples. There is a lot of real estate out there in the outfield, and as shoewizard pointed out in a comment last week, the angles caused by the bullpen entrances by the foul poles also causes some hits to go for an extra base. When a batter hits a triple that would only be a double in just about any other park, there is a hitter who gets credit for the extra base; triples are better than doubles, especially with fewer than two outs, or with a runner on first. But what about when a hitter doesn’t take an extra base, but the runner does? We adorn that credit on runners.

Fresh off some new examples in the first two Mets games this week, it’s easy to see why Chase Field has such a high park factor for triples. There is a lot of real estate out there in the outfield, and as shoewizard pointed out in a comment last week, the angles caused by the bullpen entrances by the foul poles also causes some hits to go for an extra base. When a batter hits a triple that would only be a double in just about any other park, there is a hitter who gets credit for the extra base; triples are better than doubles, especially with fewer than two outs, or with a runner on first. But what about when a hitter doesn’t take an extra base, but the runner does? We adorn that credit on runners.

Maybe we shouldn’t give hitters full credit for Chase-only triples, but we absolutely should give them some, just like it’s appropriate to credit hitters for home runs that wouldn’t go out if they’d hit it more to the left or the right. Hitters can take advantage of Chase’s dimensions on purpose, undoubtedly, to at least some extent. By the very same token, we ought to give hitters some kind of credit for taking advantage of Chase’s dimensions and the position of runners on the bases. We put pressure on hitters like Paul Goldschmidt to expand the zone or at least increase swing percentage in RBI situations, especially with two outs. Isn’t it just as likely that hitters make an extra effort to hit the ball especially hard or out of the infield in a close game with a runner on first or second?

The D-backs rank 5th in total hits right now, but also in extra-base hits — it seems like they move runners along. Really, though, the D-backs have been above average at turning base runners into runs at home, but not when they are away. Overall, the D-backs have scored 36.6% of base runners, whereas the rest of baseball has done so… 36.8% of the time. At home, the D-backs have turned 38.3% of base runners into runs, higher than the league “home” rate of 37.3%. There’s some natural selection at work, here; hitters who have done well and earned playing time for the D-backs are the ones who might best take advantage of their home confines, at least to some extent. But consider that AL teams have the DH at home and not away, and NL teams get it away and not at home, and the D-backs’ home rate is even higher than it sounds; NL teams should be below the league rate.

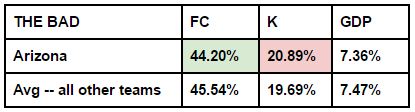

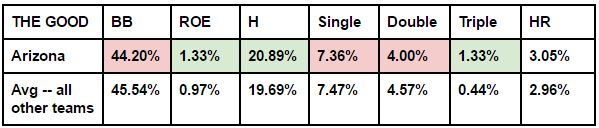

It’s largely about extra base hits, particularly triples. What I’m most interested in, specifically, is the advancement of base runners — so let’s look specifically at how the team has done with a runner on first base. Getting a hit with a runner on first already means that you not only avoided hitting into a double play or getting yourself out, but you also avoided hitting into a fielder’s choice. So let’s look at all the negatives, as well as the positives.

As it happens, despite still being 6th in the NL in runs, the D-backs haven’t been in a lot of hitting situations with a man on first; just 1,278 PAs, or 1,162 ABs (24th). They’ve managed to hit into a fielder’s choice (or other infield out) just 565 times (27th), however, and just 94 double plays (23rd).

On the flip side, they’ve reached on error 17 times (T-6th), and hit 206 singles (21st). Their rate of doubles is in line with their opportunities: 51 (27th). There’s a tradeoff there, though: 17 triples with a man on first, which not only gives the D-backs the highest total in the league, but does so in style — the next teams (Twins, Giants) have just 11.

For the D-backs, a ton of their run-scoring efficiency has been about the most extra- of extra-base hits, triples and home runs; that’s more than made up for shortfalls in singles and doubles, even if it hasn’t necessarily gone a long way toward mitigating the drop in walks and strikeouts. It could be as simple as D-backs hitters knowing when they can probably reach third safely on a ball to the outfield. I’ve long thought that the D-backs derived extra value from “long” singles, though, and I’m not sure that’s actually been true this year.

There’s a new-age-old question in baseball about whether a walk is truly as good as a single. It’s not a fair question, probably, because it’s looking forward, at what skills to value, and if you’re up at the plate, taking a borderline pitch is not as much of a play-the-odds chance as it is to hit a ball into play (and causing two outs by taking a pitch is much rarer than hitting into a double play). “Single” is an outcome, not really a skill, and if there are no runners on base, there really is no appreciable difference anyway. If you look at it from an outcomes perspective, though, a single really is better than a walk.

One reason: a walk is a time out, and on a single, all kinds of crazy things could happen, and they tend to favor the batting team (especially when there are runners). The other, bigger reason: this advancing base runners business. Walk with one out and a man on first, and you create a situation in which teams score, on average, about 0.96 runs over the rest of the inning. Single with one out and a man on first, and you might move that runner to third — a situation in which teams have scored an average of about 1.21 runs.

But singles are only better than walks to the extent that they can advance base runners an extra base. Not all singles are made equal, particularly in parks with large outfields, like Chase. Right now, hitters don’t get extra credit for the better singles, with the sole exception of RBI, which is very dependent on players other than the hitter. With an eye toward understanding how valuable the D-backs’ hitters really are, wouldn’t it make sense to know the extent to which those hitters have the skill to advance runners extra bases on singles, and how much that’s worth? The answer to those questions could help us determine how good the D-backs offense really is, and how good it’s likely to be. A hitter’s skill at long, runner-advancing singles should also be factored into lineup construction, alongside hitting for extra bases. Right? If everyone has to take turns trying to drive the bus, it’s important to know who the best bus drivers are.

In terms of whose singles advance runners, everything seems to be a function of launch angle. Because fielder’s choices and other outs are already filtered out, there isn’t much of a difference in distance or exit velocity. I pulled from the Statcast data at Baseball Savant all of the D-backs’ singles this season for which there was a runner on first base (204). 22 did not have a recorded distance from Statcast; I pushed those aside. Of the remaining 182 singles, 58 advanced the runner on first to at least third base, a healthy rate of nearly a third.

Per Statcast, the average distance for singles that advanced a runner on first to third or home was 221 feet; station-to-station singles averaged 214 feet. The bus-driving singles averaged 90.2 mph in exit velocity; the ones that didn’t were actually higher, at 91.0 mph. I think that’s because of the selection bias here; the average launch angle for a “good” single was 9.1 degrees, and the others, 7.6 degrees. For batted balls with lower launch angles to be a single, it must have been a particularly good batted ball (it being easier to field ground balls).

As a quick and dirty way to see if the D-backs were hitting more “long” singles overall, therefore, I just drew a dividing line: 8 degrees or higher was “good,” and anything at a launch angle below that “bad,” as far as singles go. But there’s not much there. In MLB, 52.6% of singles have been hit 8 degrees or higher; Arizona has hit 52.5% of its singles at or above that launch angle. This year, the D-backs don’t seem to be deriving the kind of benefit they got from long singles last year. As we look toward recalibrating the team, hitters’ penchant for long singles probably should be factored into the math.

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04 RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Every once in a while you get a beer that's just a little off... Usually happens to me at airports., 5 hours ago

Every once in a while you get a beer that's just a little off... Usually happens to me at airports., 5 hours ago If Pollock doesn’t sign with a team that wears red uniforms I’m going to be really disappointed. Working theory: Se… https://t.co/zHn9DqzEiD, 6 hours ago

If Pollock doesn’t sign with a team that wears red uniforms I’m going to be really disappointed. Working theory: Se… https://t.co/zHn9DqzEiD, 6 hours ago The work here by @Britt_Ghiroli is splendid https://t.co/c8tSq0vw3T, 6 hours ago

The work here by @Britt_Ghiroli is splendid https://t.co/c8tSq0vw3T, 6 hours ago RT @TheAthleticAZ: Plenty of #Dbacks fans gave it some time - and they still don't like the idea. The "why" from @ZHBuchanan

https://t.co/9oDlvue3fV, 15 hours ago

RT @TheAthleticAZ: Plenty of #Dbacks fans gave it some time - and they still don't like the idea. The "why" from @ZHBuchanan

https://t.co/9oDlvue3fV, 15 hours ago RT @CardsNation247: Episode 30 of the Cardinals Nation 24/7 Podcast, Hosts @ToR_Ron75 & @JMRedwine welcome @buffa82 of @KSDKSports &… https://t.co/7dbIEzcahN, 11 hours ago

RT @CardsNation247: Episode 30 of the Cardinals Nation 24/7 Podcast, Hosts @ToR_Ron75 & @JMRedwine welcome @buffa82 of @KSDKSports &… https://t.co/7dbIEzcahN, 11 hours ago

Powered by: Web Designers