Gerardo Parra Breaking the Mold in Right Field

Gerardo Parra is doing something we haven’t quite seen before: play elite right field while trailing league-average offense for that position. That’s a big reason why it took Parra until his fifth full season to finally cross the 500 PA threshold. But when he did, with 663 PA in 2013, the results were devastating: 4.5 Wins Above Replacement, good for 4th in baseball among right fielders. This massive total came despite questionable base running and below-average offense (96 wRC+, or 4% worse at creating runs than league average). The next-best right fielder in 2013 per WAR to post a below-average offensive rate? Ichiro Suzuki, who ranked twenty-first in WAR among twenty-three qualifiers.

You’ve seen them before: players who hit a little too lightly to play in a corner, but who can’t quite field for an up the middle position. Former Diamondback Matt Kata might be an example. Parra might not be; he would probably be an above-average center fielder, with good defense there (16.8 UZR/150 there in 1,032.2 career innings) and batting marks better than the average center fielder. But below-average hitters are rarely tolerated at corner positions, even at third base, and even when they offer superlative defense. The mold for corner outfielders in Major League Baseball just doesn’t fit players with Parra’s skill set. He hasn’t hit enough to be given the starting role in right if his defense suddenly became average for that position. Placeholder? Surely. But plan? Probably not.

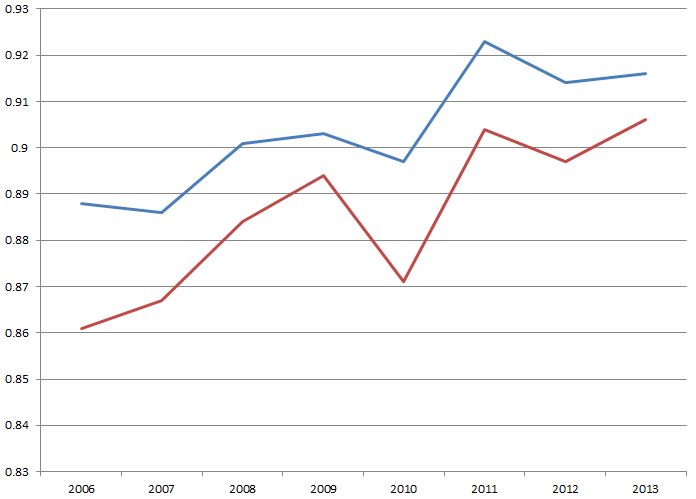

Before getting to how Parra is different as compared to center fielders, it’s important to separate what he’s done from what’s been done at that position in general. Most defensive statistics are keyed to what is average for that position that year, so if quality in general goes up, stats like Defensive Runs Saved and Ultimate Zone Rating wouldn’t necessarily show that. But Baseball Info Solutions calculates the number of balls hit to a player’s zone (BIZ) and the percentage of those balls that a fielder converts to outs (RZR). That doesn’t account for plays made outside the zone (OOZ) or quality of throwing arm, but it’s a good place to look for general defensive prowess. And RZR has been on the rise across all positions, including right field. Here’s a graph of the last eight years. The blue line is league RZR for right field; the red line is for left field, just for some context.

Parra’s defense is anything but average; he had a .947 RZR last season in right, also making 100 plays outside the right field zone and having about 9 or 10 runs’ worth of effect on the game with his throwing arm (per and ARM and rARM). 4th in WAR at any position is enough to say, conclusively, that that player is deserving of a starting role at that position — even if that WAR total is supported by superlative defensive marks that are not considered very reliable season to season. In the eleven seasons of our newest and shiniest defensive metrics (DRS, UZR), no one had done what Parra did at right field (and only Andrelton Simmons has matched Parra’s DRS mark from last year). A total that high is almost certainly a combination of extreme skill and extreme luck, and since we don’t forecast luck, we would expect at least some regression for Parra defensively in 2014.

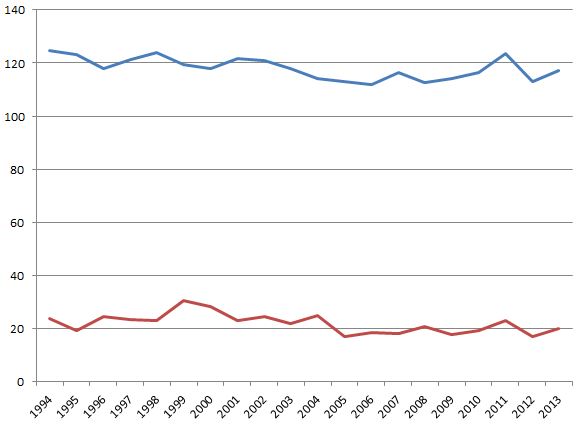

Even if you discounted Parra’s defense, however, he’s still far apart from the rest of the pack. Here’s the average wRC+ marks at the right field position for the last twenty years for qualified players (presumably, players to whom teams have chosen to give starting roles):

The blue line in the graph is average wRC+ for qualified hitters, and as you can see, it almost always flirts with 120. The red line is standard deviation; if that mark is 20 in a year in which the average wRC+ is 120, we would expect 68% of all right fielders to fall within 20 points of 120. That means we’d expect 84% of all right fielders to be above 100, which is something Parra failed to do last season. In a year in which the average wRC+ for right field is 120 and the standard deviation is 20, we’d expect just 16% of all qualified right fielders to post below-average offensive marks per wRC+.

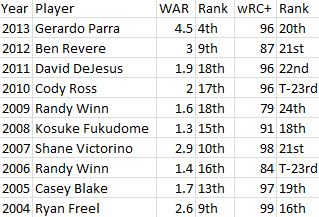

And, as hinted above, the 16% tends to not be that great overall. Even Ichiro Suzuki, the next-best RF to post a sub-100 wRC+ mark in 2013, might have had his starting role for a different reason: an apocalypse of injuries on his Yankees squad, and immense financial benefits to the team that came with keeping their Japanese advertising and marketing relationships. What Parra did is truly remarkable and truly different. Here’s the top RF for each year, by FanGraphs WAR, for any player qualified at that position for the batting title with a below-average wRC+ mark:

One could make an argument that even among these players, with the possible exception of Ben Revere, each was expected to be an asset offensively; many of these guys just had an off year (Cody Ross), were mistaken for helpful offensively (Randy Winn), or just never really panned out in MLB (Kosuke Fukudome). And expectation is the name of the game if we’re talking about the “mold” for right field. Gerardo Parra was not really expected to be an asset offensively, not after struggling so much for four years with southpaws.

Of course, playing Parra every day in right field wasn’t exactly the plan at the outset of the season; an imploding Jason Kubel and a missing Adam Eaton helped to line up that playing time. But Parra absolutely is the every day right fielder this season, after being the 4th-most valuable in the game last season. Will he get most of his days off against lefties? Absolutely. But a starter, Parra remains. And a player with Parra’s skill set being given the starting role in right field is something we really haven’t seen in Major League Baseball.

. . .

A handful of related notes:

1. Parra might not be a below-average hitter this year, even if he gets as many starts against lefties as he got last year. Two reasons for that. One, Kirk Gibson has shown in these early days of the season that his plan may be to hit Parra leadoff against RHP, but eighth against LHP. Eighth seems a little extreme to me, but obviously that limits Parra’s exposure to LHP a bit more than last year (only 26 PA in the eighth spot). The other reason? Parra might actually be pretty decent against LHP in 2014. After posting a .198 BA against lefties in 2013, Parra remade his stance, batting a little more closed with his front leg bent instead of straight. The motivating factor for the new stance seems not to be inside pitches, but weakness against lefties. Parra hit almost .300 against RHP last season. If he has even marginally better success against lefties this year (3 for 9 so far with two walks), he won’t be a below average hitter. And if that happens, Parra will no longer be so much of a mold-breaker.

2. Like right field, another position that could start to see mold-breakers is third base. I think of Manny Machado of the Orioles; despite the promise of decent defense at shortstop, the presence of J.J. Hardy has pushed Machado to third, where he offered insane defense last season (about three wins’ worth, above average). Machado was also just barely above average offensively (101 wRC+). But even Machado’s case is different than Parra’s, because Machado, still just 21 years old, is expected to hit better than that — and good enough for a starting spot at third regardless of defensive contribution. When it comes to molds, it’s all about expectations — nonetheless, Baltimore’s apparent willingness to leave Machado at third may signal a more general openness to prioritizing defense at that position, just as Parra may be a sign of things to come in right field.

3. Another thing right field has in common with third base: they are more demanding as corner positions than their opposites, left field and first base. Again, two reasons. One is frequency: there were 7,371 balls hit to the right field “zone” in 2013 (per BIZ), versus 6,714 for left. The difference is even more pronounced in the infield, with 9,919 balls hit to the third base “zone” as opposed to 6,622 to first basemen. But it’s not just about range; a player’s throwing arm is tested more at right field than at left (how often are left fielders asked to throw to first base?), just as a throwing arm is much more important at third base than at first base (or second base, for that matter). The throwing arm factor complicates “better” in the fielding context for the in-betweener, Matt Kata types. Gerardo Parra clearly found his niche in right field; his amazing throwing arm was worth almost a full win last season, and that just wouldn’t happen in center or left. If we continue to see mold-breakers at right field and third base, I anticipate that throwing arms will have a lot to do with it.

One Response to Gerardo Parra Breaking the Mold in Right Field

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04 RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

RT @ZHBuchanan: Our @Ken_Rosenthal spoke to Ken Kendrick about trading Paul Goldschmidt.

https://t.co/O5fHRlyBxD, 5 hours ago

RT @ZHBuchanan: Our @Ken_Rosenthal spoke to Ken Kendrick about trading Paul Goldschmidt.

https://t.co/O5fHRlyBxD, 5 hours ago RT @CardsNation247: We have a good show lined up for tonight. Leading off is our friend of the show @buffa82 followed by Jeff Wiser… https://t.co/eltZC0uvyg, 5 hours ago

RT @CardsNation247: We have a good show lined up for tonight. Leading off is our friend of the show @buffa82 followed by Jeff Wiser… https://t.co/eltZC0uvyg, 5 hours ago RT @juanctoribio: To piggyback off the @ZHBuchanan and @OutfieldGrass24 that the #Rays were involved in the Paul Goldschmidt sweepsta… https://t.co/spg9x7X1L5, 5 hours ago

RT @juanctoribio: To piggyback off the @ZHBuchanan and @OutfieldGrass24 that the #Rays were involved in the Paul Goldschmidt sweepsta… https://t.co/spg9x7X1L5, 5 hours ago RT @OJCarrascoTwo: Read this from the world famous, @OutfieldGrass24 https://t.co/cHUie1I5Le, 5 hours ago

RT @OJCarrascoTwo: Read this from the world famous, @OutfieldGrass24 https://t.co/cHUie1I5Le, 5 hours ago RT @TheAthleticAZ: A great source, our @ZHBuchanan and @OutfieldGrass24, for #DBacks info - and MLB Network agrees. https://t.co/QUNql4ol79, 6 hours ago

RT @TheAthleticAZ: A great source, our @ZHBuchanan and @OutfieldGrass24, for #DBacks info - and MLB Network agrees. https://t.co/QUNql4ol79, 6 hours ago

Powered by: Web Designers

[…] leaves, we have no idea why the D-backs haven’t signed Parra to an extension. He’s a very unusual type of good player, making him very difficult to value. And while defensive statistics are down on Parra this season […]