Elite Defense of Pollock, Inciarte Could Enable D-backs to Employ Five Man Infield Shifts

The D-backs are an interesting team, defensively: in 2013 they were the second-best fielding team in baseball, but in 2014, they were one of the league’s worst in defensive efficiency. We speculated on Episode 2 of The Pool Shot that the D-backs may shift more under new manager Chip Hale. I’d like to take it one step further now, after researching five-man infield shifts. But first, I’d like to paint in some additional context.

Outfield coverage can be “wasted”

One of my Big, Burning Baseball Questions is this: if you had two outfielders with incredible range and a third who was merely above-average, would you be better served having the above-average one at an outfield corner (probably left field), or would you be better off putting him in center? I’m not sure there’s a way to know the answer, because that would involve quantifying two competing factors.

The quantifiable one: the frequency with which balls are hit to each outfield “zone.” Baseball Info Solutions keeps such figures, and while their center field “zone” is bigger (in part because the average center fielder has more range), it’s clear that many more balls are hit there. In 2014, there were 4,939 balls in the CF zone according to their statistics (at FanGraphs), 3,801 to right, and 3,463 to left. Balls are hit to the center field “zone” about 30% more often than to right field, and clearly range is typically more important for a center fielder than for a fielder in right.

The harder-to-quantify one: the extent to which outfielders’ coverage can overlap. We’ve seen sharply hit balls bounce to the gaps with two outfielders reporting for duty at about the same time. And while it’s not common to see an outfielder have to call another one off to catch a fly ball, it’s not exactly rare, either.

Having a second outfielder there to catch a fly ball is not at all useful; it’s coverage waste. That’s going to happen no matter what (think infield flies), but coverage shouldn’t overlap at the expense of non-coverage elsewhere. That’s the whole idea.

But the fact remains: two outfielders with incredible range “waste” a bit of that coverage when they’re next to each other. Although overlap may happen for most teams only for fly balls of 4.5 seconds or more hang time, the best might also see their 4 or even 3.5 second hang time coverage zones overlap, at least a bit.

So in the scenario I posed in the opening, should those two amazing outfielders go on the corners, so as to both “cover” for the other fielder a bit without wasting coverage on overlap? I’m not sure. I suspect not, and it really depends on the fielders involved (including the third one — no Mark Trumbo in center field, please). Bookmark this thought, though: although outfield coverage is not typically wasted in MLB, outfielders with elite range can overlap coverage.

This is of interest to us because the D-backs just happen to have two such outfielders. Ender Inciarte played just 251.2 innings in left field, but contributed more runs saved there than all but three other NL left fielders. In center, he played just 649.1 innings, but saved 14.8 runs above the average center fielder (FanGraphs’s “Def” statistic). To put that in perspective: Peter Bourjos, thought of as a glove-only but elite CF defender, played the exact same number of innings in center, but saved just 10 runs.

Inciarte is third on the CF list in the NL, behind two other players (Billy Hamilton and Juan Lagares) who played quite a lot more. Fourth is Bourjos. Fifth: A.J. Pollock.

“Action Jackson” Pollock played a little bit less in center, with just 576 innings played there. But he, too, rates very well. Among the 36 players who had at least 500 innings played in center last season, Pollock ranked 8th with a 19.0 UZR/150 (a rate statistic), just ahead of Lorenzo Cain. After Cain’s 18.7 UZR/150, the stat drops off a cliff, with #10 Jon Jay at 12.8 UZR/150. There are many good outfielders in Major League Baseball, but Pollock is among the elite — and so is Inciarte, who ranks 3rd on that list with a 25.5 UZR/150.

So chances are there is some wasted coverage on balls in play in the outfield when Inciarte and Pollock are both playing. Probably not enough to, say, make David Peralta the center fielder when the trio are playing. But some.

The five-man infield shift

At Beyond the Box Score yesterday, I looked at the potential viability of running five-man infield shifts based not only on the situation, but based on the batted ball profile of the batter. Using Ben Revere as a test or illustration, it looked like it could only ever be a close call for batters qualified for the batting title, and that for every such hitter except the most extreme (Revere), it wouldn’t be worth it.

The scenario is this: if you have a batter who constantly hits ground balls but who sprays them everywhere in the infield, it could optimize the defense to put a fifth fielder, say, in the whole behind second base. To make sense, the extra fielder would still have to be able to throw the runner out at first; therefore a fielder behind the keystone might have to shade to the first base side, and having a short fielder would only work between the first and second basemen, not on the left side between the third baseman and shortstop.

But I raised two issues in that article that I didn’t explore: 1) how a five-man infield could make routine sense against pitchers, and 2) how the team’s fielders would need to be of a particular type to take advantage.

1. Pitchers hitting

Most MLB pitchers were once fantastic hitters, maybe the best on their high school teams. That’s a point my late uncle impressed on me a very long time ago. But most MLB pitchers are not MLB hitters.

There are exceptions. Madison Bumgarner produced runs at a rate 15% above league average (115 wRC+), and that means 15% above non-pitcher hitters (including pitchers, the league-average wRC+ is not 100, but 96). Travis Wood had a 93 wRC+. Zack Greinke, 74 wRC+. And a few others hit about as well as a particularly poor hitting backup catcher (Shelby Miller, Jacob deGrom, Mike Leake).

Those are the top 6 hitting pitchers last season, among the 50 who had at least 50 PA. One thing they had in common was a fairly low ground ball percentage, like Bumgarner (31.6%) and Wood (34.2%). The other four were between 40.9% and 57.4%. Only 7 of the other 44 pitchers had a ground ball percentage below 60%.

If the Revere illustration did teach us that the threshold for a five-man infield shift might be around 60%, well then, it might make sense for teams to shift all pitchers with five infielders — once a few pitchers with demonstrated hitting ability are weeded out. In fact, the overall ground ball percentage for NL pitchers last season was 63.0%.

The overall fly ball percentage was 20.5%. But more of pitchers’ batted balls were actually fielded by outfielders; about one in eight ground balls sneaks through the infield in general, and most line drives (pitchers had a LD% of 16.5%) get out there too. Part of the point of a five-man infield is to limit those very same ground balls and even cut down a bit on the line drives, of course, but the outfielders do still matter quite a bit.

2. The D-backs happen to fit this approach

The situation in which I’d recommend a five-man infield is: 1) pitcher hitting who is likely to have a ground ball rate of about 65% or higher; 2) pitcher hitting hits far fewer balls to one part of the outfield than others (i.e., pulls the ball, or only goes the other way like Revere); 3) no runner on first base.

It just so happens that the D-backs can accommodate this. Ender Inciarte and A.J. Pollock are both elite defenders who cover a lot of ground. Moving them apart from each other would all but eliminate wasted coverage, although it would still increase the number of hits in the gap between them (batted balls with low hang times). With respect to covering the outfield, after a survey, I think the D-backs may be more suited to playing with two outfielders than any other team in the NL.

Chase Field makes the case more compelling, in my view, because at the foul poles, the wall is angled. If Inciarte were playing left/left-center and Pollock was the center fielder shading to right field, and if a ball did happen to shoot all the way down the right field line, the ricochet could help Pollock get to the ball just a bit sooner than at other parks.

It’s the infield side that is the trick. Back in the Martin Prado days, the transition would have been seamless. In 2015, the outfielder who would be shifting to the infield would probably be Mark Trumbo, Cody Ross or David Peralta.

Neither Ross nor Peralta has played a lick of infield in the majors (although Ross did pitch one inning in 2009). Trumbo is the most obvious choice. If you shifted Trumbo to the infield, he would man first base, with Gold Glover Paul Goldschmidt likely playing in the hole between the traditional first and second basemen slots. He’d have to practice that, of course. But he does seem to have that capability.

The D-backs can and probably should consider working Ross out at first base, as well, and not just for this purpose. Trumbo is Goldy’s backup, but what if Trumbo is not playing? What if Trumbo is frequently removed in the 7th or 8th innings next season in favor of a defensive replacement, and Goldy needs to come out of the game? The D-backs no longer have a third-string first baseman with Eric Chavez and Martin Prado both gone, and so training Ross at first might make sense and make him worth keeping on the roster.

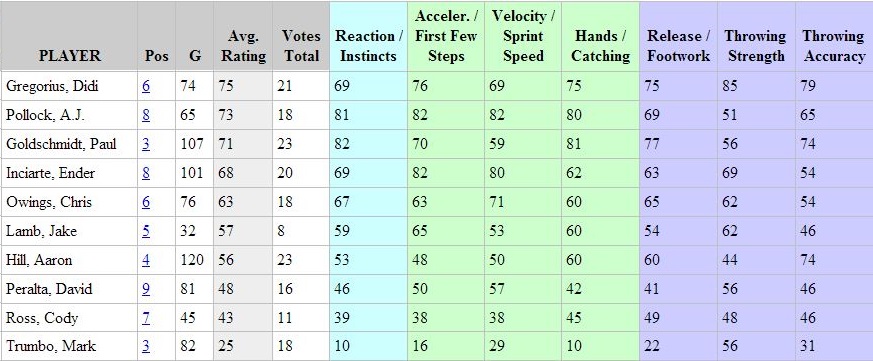

The results of Tom Tango’s Fans Scouting Report are now out, and they are perfect for this exercise: responders are instructed to not take the player’s position into account when rating individual players’ individual skills. Check out the ratings of the likely infielders, as well as Peralta, Ross and Trumbo:

You may need to click on that to see, but based on these numbers, it’s not easy to see Ross as a defensive asset — he has been one in the past, however, and maybe one more year removed from surgery, fans will scout him as being more agile out there. Trumbo doesn’t look like a good bet to move to first base, but then of course, these numbers make it seem like he’d be a below-average DH, defensively (is that a thing?).

It may be, then, that with Peralta, Ross and Trumbo all rating poorly in the categories most important for infielders, it would be the outfielder-turned-infielder that would have to play first base. And so, we can pretty much eliminate the short right fielder option — that would either force Goldy to play in the regular 2nd baseman’s slot, or it would make him an outfielder. Maybe that’s not so crazy, but the better option seems to be to keep Goldy closer to where he’s used to playing, in the first base/second base hole, with Aaron Hill or Chris Owings moving over behind the second base bag.

The return on five-man infields is never going to be huge. It may be that it does optimize the defense properly in some situations, but even then, I agree that the juice might not be worth the squeeze. If we can convince the new D-backs Powers That Be of a few things, this would not be one of them. But I do think it can work — and it sure is fun to think about how the D-backs might accomplish it.

2 Responses to Elite Defense of Pollock, Inciarte Could Enable D-backs to Employ Five Man Infield Shifts

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

#Dbacks' 2018 1st round pick Matt McLain hit .203/.276/.355 as a freshman at UCLA last year. This season? A tidy li… https://t.co/yM48j1ebrr, Mar 07

#Dbacks' 2018 1st round pick Matt McLain hit .203/.276/.355 as a freshman at UCLA last year. This season? A tidy li… https://t.co/yM48j1ebrr, Mar 07 RT @OutfieldGrass24: Who's that under the radar player who you are banking on to break out this baseball season? Someone who's not regularly in the headlines?, Mar 06

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Who's that under the radar player who you are banking on to break out this baseball season? Someone who's not regularly in the headlines?, Mar 06 Just say "plague" already https://t.co/qkcwY2Omub, Mar 06

Just say "plague" already https://t.co/qkcwY2Omub, Mar 06 RT @wickterrell: You can certainly argue that he already has broken out, but I'm expecting massive things from Ramon Laureano this y… https://t.co/ejJPu9AEnd, Mar 06

RT @wickterrell: You can certainly argue that he already has broken out, but I'm expecting massive things from Ramon Laureano this y… https://t.co/ejJPu9AEnd, Mar 06

Powered by: Web Designers

Anybody doing any research on how many times in this world series the royals/giants have hit into the shift? Can it really keep working?

last night giants took advantage of the shift. The younger more atheletic lh should be to handle the shift with bunts. The seth smiths/chris davis’ maybe not as much. I don’t know, shifts are limited to an extent in a lot of ways. The other old school defensive tendencies though will still probably dominate over the long haul. The Bochys of world will make sure their teams exploit the shifts. How many singles to right that get taken away by the shift especially in the playoffs before a manager calls for bunts to the left side, since the shift is prevalent against lefties.