An Alternative Answer to Trevor Cahill

The saying that “there’s more than one way to skin a cat” always struck me as being spoken in poor taste. First, I’d argue that cats don’t project to taste well (low fat content, gamey, etc.) and, second, that the visual is distracting to whatever analogy the speaker is trying to make. No matter the argument, as soon as you throw that skinning cats thing out there, I’m completely unable to focus on the topic at hand. So, for argument’s sake, let’s change that analogy and say that there’s more than one way to end up with a 5.61 ERA. While it has the added benefit of being true, this analogy pertains specifically to our recent favorite subject here at Inside the ‘Zona, Trevor Cahill. Let me explain.

Ryan did some fabulous work late last week when he dove head-first into what was behind Trevor Cahill’s downturn. As we know, there’s more than one way to be bad, more than one way to end up with a 5.61 ERA. But we also know that ERA can be misleading, at least if we’re trying to find out how good a player is. ERA tells us what happened during a season while stats like FIP and SIERA tell us how talented a pitcher is. There’s a big difference here, since we can expect talent to carry over in a relatively stable fashion from year-to-year. We cannot, however, expect the same events to happen from year-to-year. If you’re looking to make bets, you want to know how good someone is.

And the results were kind of surprising and kind of not. While Cahill’s ERA has fluctuated wildly from one season to the next, his advanced numbers, FIP and SIERA, have remained pretty steady. Ryan was right in surmising the following:

Unless I’m missing something, the remaining explanations fall into three buckets:

1. Something Cahill was doing that led to his pitches getting hit harder more frequently (not luck).

2.Balls falling in for hits more frequently than we would expect them to (luck, or defense)

3.Inconsistency; SIERA and FIP have guessed wrong because they’ve assumed that Cahill’s bad stuff weren’t as lumped together as they were.

Through some very sound analysis and reasoning, Ryan was able to rule out, via data, the idea that Cahill was getting crushed more frequently, that his defense was letting him down and/or that FIP and SIERA were the incorrectly evaluating him. That left one final conclusion: Trevor Cahill has been, to some degree, the victim of bad luck. And while that’s surely part of the answer, I wanted to know even more. So just like you can skin cats a whole bunch of ways and there’s a boatload of ways to arrive at 5.61 ERA, there are other ways to evaluate Trevor Cahill.

*Note: I want to first point out that I wouldn’t have been able to come up with the following findings had it not been for the work Ryan did the first time around. That’s the beauty of teamwork, I guess. Ryan does the hard part and I steal from him. You’ve probably noticed this. I’m just kidding. Kind of. Okay, back to work.

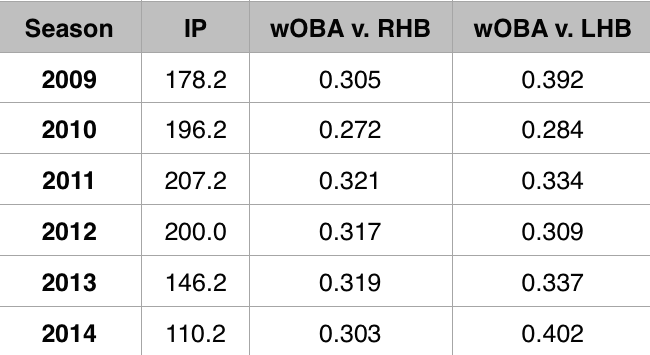

Random variations happen and we see them all of the time, but Trevor Cahill looked to be struggling in 2014. I don’t know how to say it more succinctly, but he just didn’t appear to be able to put away hitters at times like we’d seen in the past. Sure, he wasn’t amazing in 2013, but he was fine. Last season appeared worse, for some reason. Therefore, I continued digging since Ryan had already eliminated a number or reason why he may have scuffled. The following surprised me:

Do you see the outlier there? Cahill got smashed by lefties last season, and since he’s a righty, a performance split isn’t exactly unforeseen. But the magnitude as to which it happened was certainly larger and more overstated than anything we’ve seen from him in the recent past. It was way outside the norm and piqued my interest immediately. He was pretty good against right-handed batters, actually, but the left-handers completely had their way with him.

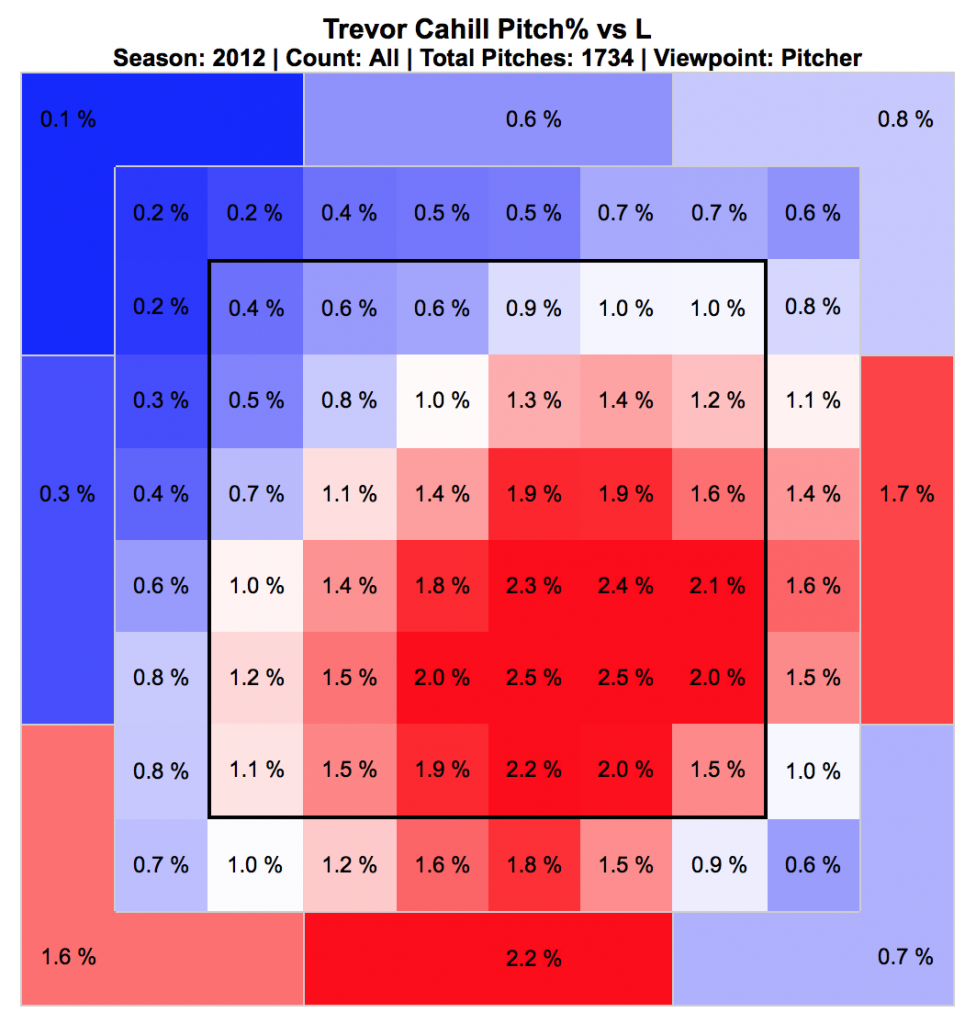

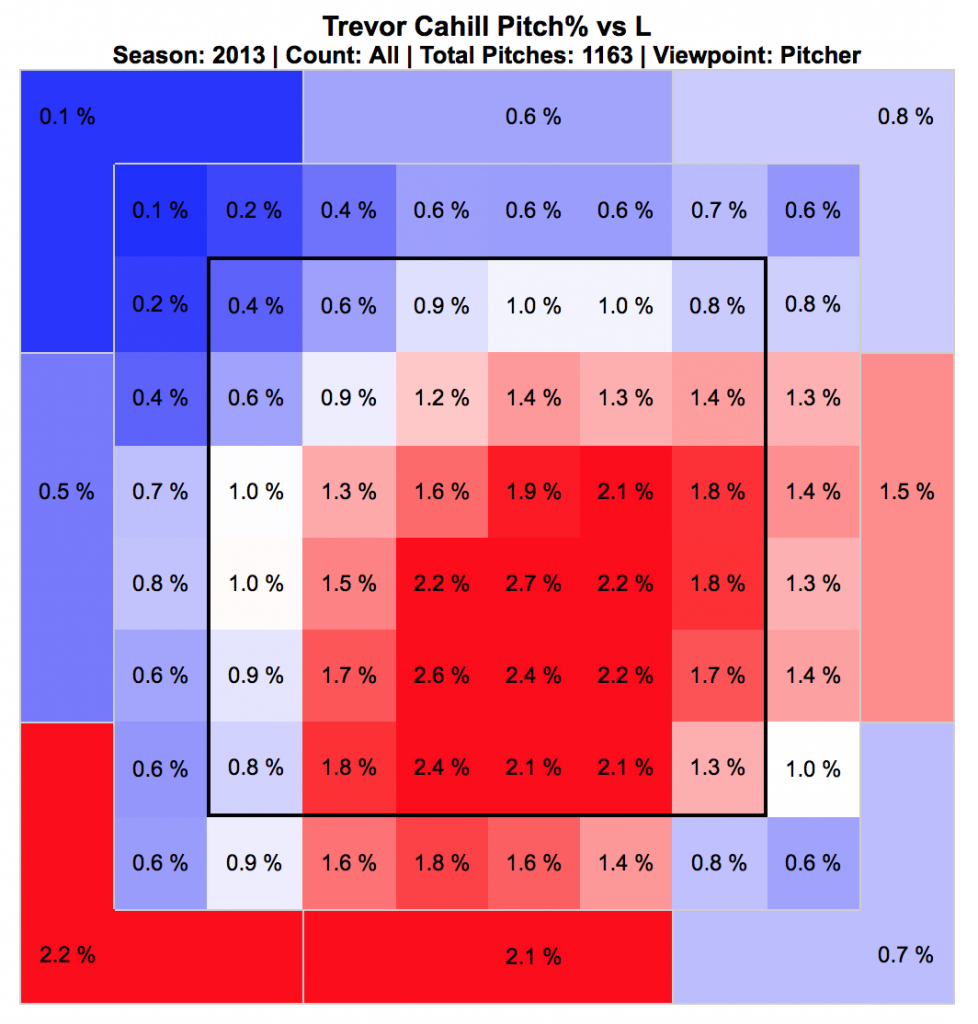

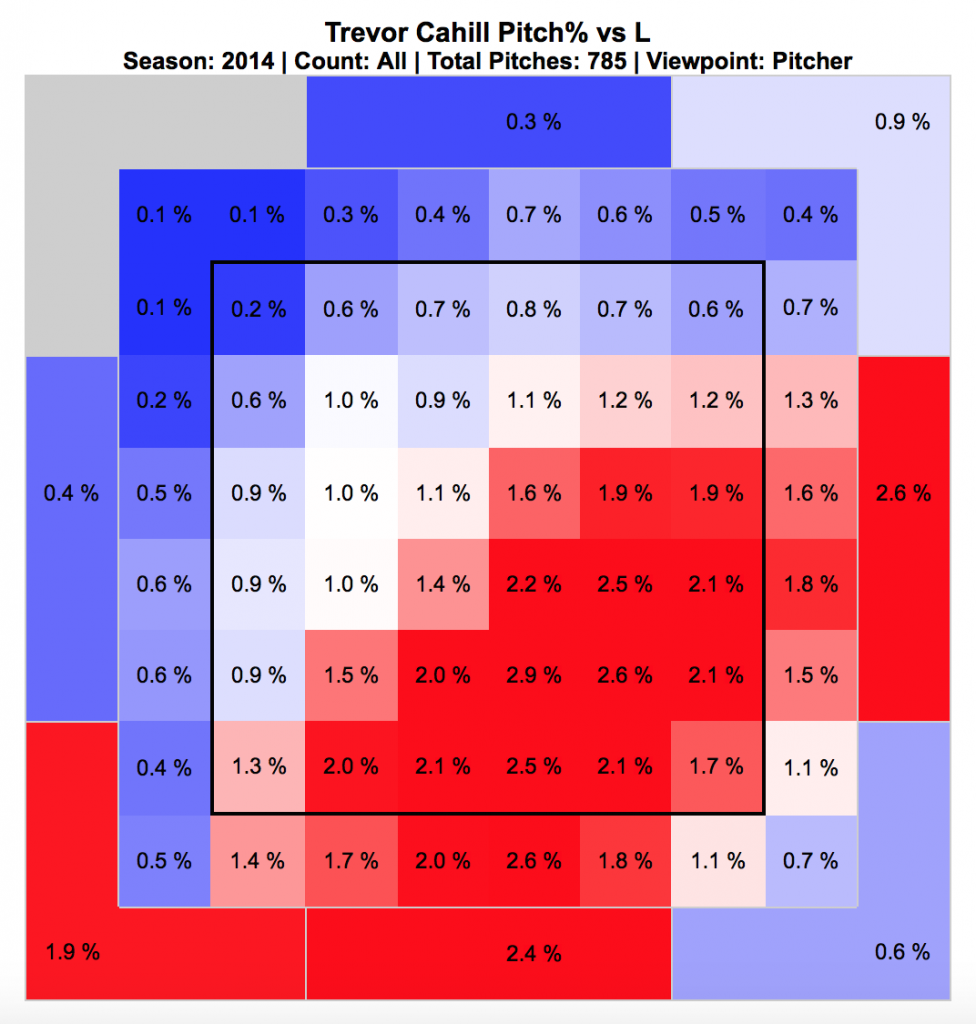

I immediately went to his heat maps to see if there were any major changes. There really weren’t, at least nothing so dramatic to suggest that he was doing something completely different. He did a slightly better job of staying away from lefties in 2013, but was nearly identical in 2012. There’s just not enough here to explain his 70-ish point wOBA spike against lefties.

2012

2013

2014

But I got to thinking about something else: what pitch do pitchers usually rely on to dispatch opposite-handed hitters? They need something that breaks away from the hitter, meaning for Cahill that the pitch would need to have arm-side run. His slider moves towards left-handed batters, and his curve does a little bit, too. But his changeup, just like nearly all changeups has a bit of fade as it falls away from opposite-handed hitters. This explains why elite changeup pitchers usually have the lowest platoon splits; they’re able to neutralize the hitters that typically would have the greatest advantage over them.

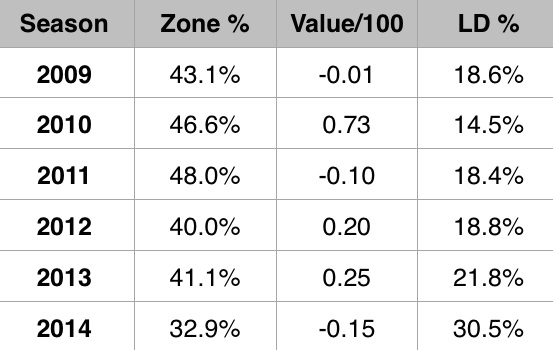

So how was Trevor Cahill’s changeup in 2014. Not good, to be honest. It lost some movement even though he wasn’t necessarily throwing it harder, but the real problem came when he tried to throw it for strikes.

He struggled to hit the zone with the pitch at a rate that was downright shocking. If he couldn’t throw it for strikes, it wasn’t likely to be considered a true threat. When he did get it close enough to the strike zone for hitters to make contact, they hit line drives at an astonishing rate, and given that we know how line drives end up hits over 70% of the time, it’s no wonder the pitch graded out with a negative value. Since pitch sequencing is a very real thing, losing one weapon likely put additional stress on the rest of his arsenal. That’s not good for a guy who couldn’t consistently command his sinker, elevating the need for him to showcase strong breaking pitches (which he actually did).

I guess the takeaway here is that Trevor Cahill probably was somewhat unlucky in 2014. But we know that luck doesn’t always exist in a vacuum. Sometimes a pitcher makes his luck, be it through losing fastball velocity, command in general, or losing an important pitch in his arsenal. The ripple effects are felt throughout the repertoire given that a guy like Trevor Cahill only really has four options to work with. If one of those four goes away almost entirely, well, he becomes more predictable. Mix that in with poor sinker command I think we can see a reason for his luck changing.

At the root of the problem, there’s a blend of two things in my mind: some random variance and a pitcher with a diminishing arsenal. Hopefully some adjustments to his mechanics will help him find his rhythm. If they don’t, the Diamondbacks are likely stuck with a $12 million reliever for 2015. If they do help him, then maybe they have a valuable trade asset on their hands. There’s a lot riding on him finding his changeup again, even if his sinker command remains touch-and-go.

*All stats and heat maps via FanGraphs

15 Responses to An Alternative Answer to Trevor Cahill

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04 RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Every once in a while you get a beer that's just a little off... Usually happens to me at airports., 4 hours ago

Every once in a while you get a beer that's just a little off... Usually happens to me at airports., 4 hours ago If Pollock doesn’t sign with a team that wears red uniforms I’m going to be really disappointed. Working theory: Se… https://t.co/zHn9DqzEiD, 5 hours ago

If Pollock doesn’t sign with a team that wears red uniforms I’m going to be really disappointed. Working theory: Se… https://t.co/zHn9DqzEiD, 5 hours ago The work here by @Britt_Ghiroli is splendid https://t.co/c8tSq0vw3T, 5 hours ago

The work here by @Britt_Ghiroli is splendid https://t.co/c8tSq0vw3T, 5 hours ago RT @TheAthleticAZ: Plenty of #Dbacks fans gave it some time - and they still don't like the idea. The "why" from @ZHBuchanan

https://t.co/9oDlvue3fV, 14 hours ago

RT @TheAthleticAZ: Plenty of #Dbacks fans gave it some time - and they still don't like the idea. The "why" from @ZHBuchanan

https://t.co/9oDlvue3fV, 14 hours ago RT @CardsNation247: Episode 30 of the Cardinals Nation 24/7 Podcast, Hosts @ToR_Ron75 & @JMRedwine welcome @buffa82 of @KSDKSports &… https://t.co/7dbIEzcahN, 10 hours ago

RT @CardsNation247: Episode 30 of the Cardinals Nation 24/7 Podcast, Hosts @ToR_Ron75 & @JMRedwine welcome @buffa82 of @KSDKSports &… https://t.co/7dbIEzcahN, 10 hours ago

Powered by: Web Designers

Also note that his 2014 performance was close to 2009, and that 2010 was the real outlier. Many pitchers have flashes of brilliance, which would be 2010 for Cahill. Like the 2011 team one good run can create unrealistic expectations, and extreme disappointment when the law of averages transforms Mount Victory into Death Valley.

Dan, that’s something Ryan and I have spoken privately about a number of times. He was indeed brilliant in 2010 as measured by ERA, but the peripherals and numbers underneath his performance suggest that he was really pretty average (4.19 FIP). His BABIP (.236) was unsustainably low by a wide margin, yet the D-backs decided to buy on him anyways, proving one of two things: either they didn’t bother to check the validity of the results, or, they just didn’t care at all about advanced numbers. Neither would surprise me given who was steering the ship at the time. But looking at those peripherals and advanced data, his subsequent fall to reality isn’t really much of a surprise at all. I’m inclined to chalk it up to an ill-advised purchase out of ignorance at this point, and now the team is stuck with the money he’s owed. Let’s hope for smarter decision making going forward.

Privately… and in print on Friday 🙂

My guess is that advanced metrics were ignored entirely. And, unfortunately in the case of Hellickson, this mistake is not contained to the old regime. The disparity between FIP and ERA in his good years is even greater than that of Cahill.

Good stuff. The two things that jumped out at me about Cahill’s numbers last year were how bad his sinker was and how bad his change-up was. From a movement perspective, it looked like his sinker was moving more which had me wondering if it was moving too much causing him to “hold it back” when he fell behind to keep it in the zone (his sinker zone% was 42.3%, by far the lowest in his career), leaving something for the batter to crush. Looking at his change-up, batters were swinging at it like crazy last year (highest swing% of his career at 53.9%). My first thought was that he was tipping his change-up but now I think he’s tipping his sinker. All of his other pitches have a higher swing% except one; his sinker. His sinker has historically been his best pitch. It would make sense for batters to not swing at this pitch but swing at everything else. It would also explain why his sinker, when it is swung at, is getting crushed.

There was some really interesting results with the swing% and whiff% rate of his CH, but I feel like, to a degree, it was impacted by his ability to command it for strikes. These things start to get hard to separate at some point. Him not being able to throw it in the zone had an effect, that’s for sure. And his sinker, well yeah, it just moves so much that he can’t command it. The new arm angle, if he’s able to harness it, should take some of the run out of the pitch, help him locate it.

You are all embarrassing. Your BS stats and numbers mean nothing. Cahill is a bad MLB pitcher. It is that simple. No one needs metrics and advanced stats to know that. What is wrong with you?

How could I have missed this? Thank you for cutting straight to the heart of the matter. I’m sure the data about how he couldn’t command his sinker and threw bad changeups has nothing to do with him being bad. Those things didn’t make him bad, he just IS bad. I get it now. Thank you!

Logan, That is an embarrassing reply. Why are you reading a analytics site if you don’t appreciate how they help in evaluating baseball players? I don’t know if analytics can solve everything in baseball but using them in the case of Trevor Cahill sure would have saved us (Diamondback Fans) all a lot of grief.

What is more likely:

1. That “bad luck” explains why a lot of pitchers have struggled with the D-backs in the last two years despite succeeding elsewhere before or after their D-backs tenure.

2. That something is going on which is making D-backs pitchers look worse than they actually are.

I’m going with #2. That means adjusting expectations; very good pitchers may look merely good, good may look merely average (Miley?), average may look kind of bad (Cahill?).

And if you’re still with me: that means not giving up on guys when you can show that their performance doesn’t match their skills or their peripherals.

Failing to make that kind of adjustment means we’re destined to be disappointed by most pitchers who get called up or signed or traded for. It’s like somebody left a crayon in the washing machine: yeah, our white T-shirts have been mostly coming out mostly green, and yeah, our white T-shirts aren’t supposed to be green. But where do we get by blaming the T-shirt?

Huh? You lost me with the crayon/t-shirt analogy. Even if the crayon was green – a variable which I am left to assume – still makes my head hurt.

So when his sinker wasn’t working in the past, he was still a 4 pitch guy, not great, nothing overpowering, but could survive. When his changeup went away he became a 3 pitch guy on those days, and without an effective changeup, his fastball loses something, no wonder he stunk. Great work here, way to show your work on how you got to the change.

Jesus, that’s really getting shelled versus lefties. Looks pretty localized, now. At Brooks, I’m looking at a patently absurd 34.62% LD% on the changeup by left-handed hitters. But it’s still really everything; they also had a 34.55% LD% on the sinker, and a 36.36% LD% on the four-seam.

This Cahill thing is getting even more obnoxious. Now we know it’s really only about lefties, but…Why???!?!? Tipping pitches in a way that only lefties can see? He threw twice as many sinkers as changeups to lefties. What else could possibly explain rates THAT absurd for two pitches that are so different?

Montero…all monteros fault. Hes a sinkerball pitcher, change is supposed to be mostly sink type action rh fading away from lefties, as most lefties are looking to turn on it and lift their heads instead being fooled. Fast sinker basically hitters think they have one to crush but it disappears. Looking at cahill stats logan may most right. The reason for his big league existence is the sinker and change, which are both are not fooling anyone on.eitherside.of the plate. That said logan is most correct this round. Dont need anymore analysis than that really. Lets hope it mostly was a gibby/monterrible situation.

Here is a question to research. Did Cahill actually perform better with Tuffy than Miggy?