Chase Anderson and a New-Found Sinker Reliance

Chase Anderson defied expectations last season. After a promising early career in the minors, he put up a scintillating 2012 line at Double-A: a 2.86 ERA in 21 starts, backed by a very good 8.39 K/9 and a borderline excellent 2.16 BB/9. Things looked good. But they did not look good the following year in 88 Triple-A innings (13 starts, 13 relief appearances), when a rise in walk rate and ridiculously poor luck (58.9% left on base percentage) left him with a 5.73 ERA to end the season. The Triple-A line and Anderson’s old-for-his-level age made preseason projections bearish; the 2014 pre-season ZiPS projections had Anderson with a 4.98 major league ERA with the peripherals to match, making him exactly replacement level.

Demoted to Double-A to start the 2014 season as a starter again, all Anderson did was dominate; he gave up three earned runs in six starts for a 0.69 ERA. And despite how things looked twelve months ago, that made Anderson the right guy at the right time to get installed in the MLB rotation after last April’s pitching apocalypse.

Whether Anderson has caught lightning in a bottle remains to be seen. He pitched to a 4.01 ERA in the majors, his 4.22 FIP and 3.78 SIERA suggesting that that was not a mirage. It made him one of the most effective pitchers last year on a particularly ineffective staff, and it has at least earned him a very long look this spring despite at least a dozen legitimate rotation candidates.

The key to Anderson’s success has and will always be his changeup. It is crazy effective, and while he throws it at a higher frequency than most starters, there has been such a gap between his change and his other pitches that it probably makes sense to throw the change more, and more frequently in unpredictable counts. One of the reasons he can probably get away with that is that he really throws two completely different changeups. And as you might imagine, that makes precise analysis of PITCHf/x data on the changeups much more challenging.

But it need not be all about the change. From this excellent piece from Nick Piecoro and Zach Buchanan:

One thing that plagued him at times last season was the home run ball, and to help combat that Anderson said he’s working to incorporate a two-seam fastball into his mix more often.

“I’m probably more of a fly-ball pitcher than a ground-ball pitcher, but I want to become a guy who can get more ground balls when I need to get ground balls,” he said. “I’m going to stick to my strengths no matter what, but that’s what I’m working on, more of a two-seam now and throwing my curveball more for strikes this year.”

Ah, the sinker. If you listened to Episode 17 of The Pool Shot, you know that we’re all about validation at the moment. So forgive me if I point you in the direction of this, from Inside the ‘Zona author RG last June (!): Chase Anderson Needs to Throw More Sinkers. In it, RG paid particular attention to Anderson’s differing habits when facing lefties and righties; he noted that while Anderson had thrown the sinker 32.77% of the time to lefties, he threw it just 15% of the time against righties, favoring the four-seamer. RG was writing less than two months into Anderson’s major league tenure, but as he showed, it was already very clear that the sinker was performing much better than the four-seamer:

Naturally, this led me to look at which pitches right-handed batters were having success against. They’re slugging an astonishing .816 against Anderson’s four-seam fastball. Against his sinker, they’re only slugging .435. It’s not like the batters are getting lucky either—55.88% of the four-seamers put into play by right-handed batters are line drives. That is leaps and bounds beyond what is acceptable for a pitcher. Again, the sinker is faring much better. Only 26.09% of the sinkers in play from righties have been line drives.

The four-seam fastball has explained Anderson’s propensity for giving up home runs, and it has explained his lack of success against right-handed batters. The solution seems simple: throw more sinkers and less four-seam fastballs.

Naturally, Anderson steadily decreased his sinker percentage for the remainder of the season: 23.78%, 20.58%, and then 11.16% for the final three months. Naturally, Anderson’s ERA for those three months were 2.78, 4.65, and 5.63. Naturally, I’m going to use this opportunity to suggest that you check in on insidethezona.com every once in a while.

I am also really enjoying this whole block quote thing. So allow me to do it again, in part because it seems relevant, and in part because this next piece is no longer copyright protected and therefore I can block quote it even without one of those pesky fair use requirements. From Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Sinker Reliance,” quite possibly the best essay ever written:

Why, then, do we prate of sinker-reliance? Inasmuch as the vertical movement is present, there will be power not confident but agent. To talk of reliance is a poor external way of speaking. Speak rather of that which relies, because it works and is. Who has more sinker obedience than I masters me, though he should change his grip. Like a base ball, round him I must revolve by the gravitation of seams…

…It is easy to see that a greater sinker-reliance must work a revolution in all the front offices and relations of men; in their religion; in their education; in their pursuits; their modes of pitching; their association; in their property; in their speculative views…

…Another sort of false prayers are our regrets. Discontent is the want of sinker-reliance: it is infirmity of will.

This is incredibly appropriate, maybe even unbelievably so? But all the more impressive in that Emerson wrote it just two years after Abner Doubleday invented the game (which is about as believable). Or, maybe Emerson was going off of Massachusetts Base Ball a/k/a Four Old Cat.

I’m not sure if we and Anderson may be discontented for want of sinkers (“infirmity of will” is taking it way too far, Ralph…pump the brakes). Still, there are some good points here, and we’ll take a page from this book — instead of speaking of sinker reliance, we’ll speak of that which relies.

Back when I was urging Anderson to throw his changeup more, his four-seam featured prominently. Yes, when one pitch is one of the most effective in the majors and the other is one of the least, it’s a knee jerk reaction to want the latter pitch thrown less, in favor of the former. But as then, I’ll acknowledge now: it may be that hitters whiff on the change so badly and so frequently because the four-seam is so hard to resist that hitters will look for it anyway. Change the balance, and the changeup will probably be less effective on a pitch-per-pitch basis. The difference was so huge that I hoped (and hope) that Anderson will try relying on it more anyway, but the importance of the ineffectiveness of the four-seam to Anderson’s effectiveness overall is something to keep in mind.

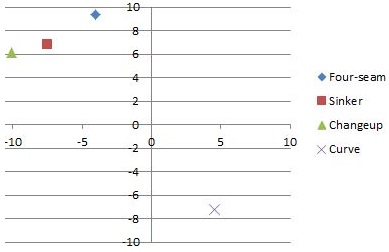

The movement on Anderson’s pitches was very consistent from month to month last season, so let’s focus on 2014 averages. And, what the hell, let’s make it a scatter plot.

You can think of this as being from the catcher’s perspective. The center of the plot would be as if a ball had no air resistance moving it at all; even the sinker gets upward movement (6.86 inches, on average) from backspin. And yes, even the changeup. Gravity is not included in these Brooks Baseball numbers, but gravity exerts the same force on every pitch (just for less time if a pitch is faster).

The scatter plot is misleading because of the curveball, which is so different that it never looks the same (unless you’re Ted Lilly, and you have the stomach for throwing mediocre fastballs that hang out in the same path). Yes, you might be caught off balance by a curve you’re not expecting, but with respect to all of those pitchers who aren’t Lilly, you’re never fooled into thinking the curve is something it’s not.

That’s me saying: don’t underestimate the importance of the differences in movement on the other three pitches. The six inches difference in horizontal movement between the four-seam and the change is enough for a pitch to go from exactly on the sweet spot to missing the bat entirely. The three-and-a-half inches between the four-seam and the sinker is enough to turn a particularly hard-hit ball to a particularly soft-hit ball. And, more importantly for our current purposes, the two-and-a-half inches difference in vertical movement between the four-seam and sinker is enough to turn a line drive into a foul tip. It’s just like Emerson said: the power of the sinker will be its agency.

There is another dimension in which pitches can be different: velocity. From Brooks Baseball release speeds, I report that between the four-seam (91.94 mph) and sinker (91.45 mph) there is almost no difference at all. The changeup has that classic 10 mph gap (81.95 mph). In fact, as compared to the four-seam, that’s a 9.99 mph gap. Might as well be precise.

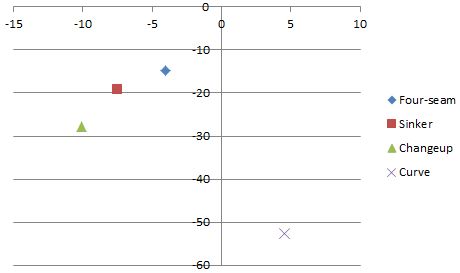

Remember how I said that first scatter plot was without gravity? Here’s the same thing but with gravity included:

The changeup falls off the table in part because of its natural movement, but also in part because it takes 11% longer to actually reach the plate. One would think that the changeup would be easier to distinguish from the fastballs than it would be to distinguish between the two fastballs. But while it may be easier, it’s clearly not easy; we know that from the changeup’s devastating effectiveness.

Still, the two fastballs have to be a difficult read from each other. A hitter has only the pitches’ spin (“am I seeing fewer seams?”) to make that split-fraction-of-a-second decision, and there is just enough difference in movement, both horizontally and vertically, for a hitter to fail to put the ball in play (or, fail to do that well) by shooting the gap (unless he misses the gap, and happens to miss it in favor of the right pitch). One would think that would be difficult. But one need not speculate; we have data. Big, juicy data.

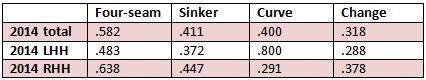

The trends that RG identified in his piece last June did actually continue through the rest of the year:

Basically: a 15% or so difference between the fastball usage based on handedness (favoring the four-seam more against RHH), and a 15% or so difference between the curve and change usage (favoring the curve against RHH). But did that work? The main thrust of the “throw more changeups” piece was that the gap in effectiveness was so large that even if throwing it more frequently made it less effective on a pitch-by-pitch basis, throwing it more could still mean Anderson became more effective overall. Can we say something similar about the sinker?

Part of Anderson’s motivation to mixing in the sinker more, according to the Piecoro/Buchanan piece, is avoiding home runs. That’s not a trivial thing. So to make sure home runs make a difference in what we’re looking at, let’s look at the same table, but with slugging percentage instead of pitch frequencies:

So the whole thing about favoring the curve over the change against righties, but the change over the curve against lefties? Good plan. And, um… a .800 slugging percentage on the curve by lefties is a little like saying that lefties were hitting .200 against it… and only hitting home runs. Check, please.

Before I pick up the tab, let’s talk about the other spicy meatball that Anderson has been serving up: that four-seamer, against righties. I get why the sinker didn’t necessarily feel like a good alternative; it was definitely less effective against righties than against lefties. But consider this: Paul Goldschmidt has had slugging percentages of .551 and .542 in the last two seasons. The leader in slugging percentage last year among qualified hitters was Jose Abreu, who sported a .581 SLG. That .638 SLG for the four-seam against righties is scary.

The .438 SLG on the four-seam against lefties wasn’t great, don’t get me wrong. The sinker fared better, which helps explain why Anderson threw it almost as often as the four-seam when facing lefties.

Dumping the curveball when facing lefties seems like a good experiment to try, especially since it shares zero attributes with his other pitches and wasn’t necessarily all that useful for deception as a show-me. Far more important, though, seems to be getting away from that four-seam against righties, favoring the sinker more instead of throwing the four-seam almost half the time.

I feel pretty confident about these inferences, but that’s all they are: inferences. In the end, ideal pitch selection would end up with very small gaps in “pitch values,” such as they are (unfortunately, those calculated at FanGraphs use data that doesn’t distinguish between the four-seam and the sinker). The only way to get there is through experimentation.

We will return, then, some time after Anderson has trotted out his new commitment to the sinker in game settings. There is really good reason to be optimistic. Just one word of caution: it’s one thing to throw a pitch more, but as explored here, if it is routinely thrown in certain situations such that a hitter can make solid educated guesses about what he’s about to see, some part of the force of having four usable pitches is lost. The hard part may be that the sinker may not have good results, if the slugging percentages from last year are any indication. Let’s hope they stick with it; through making hitters wait on his change, Anderson knows better than most that patience is a virtue.

9 Responses to Chase Anderson and a New-Found Sinker Reliance

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Starting 2022 with a frigid dog walk sounds just lovely https://t.co/xoLZSZBpGp, Jan 01

Starting 2022 with a frigid dog walk sounds just lovely https://t.co/xoLZSZBpGp, Jan 01 I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30

I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30 Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29

Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29 Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27

Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27 Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Powered by: Web Designers

great article, his stretch from may 28 to aug 14, was pretty encouraging, for all of us, and gotta give credit to Gibby and Miggy, for a lot of that. What sticks out is this guy definitely has a career as lh specialist, due to the change ups, so he’s a major leaguer for a long time. His ability to neutralize lh with his changes, is further proof of what is wrong is with Cahill too.

So rh’ers are getting fat off his 4 seam, so that tells me rh’ers are cheating off it. Shouldn’t be too hard for him to make adjustments, against rh’ers since he is effective with his curve, against them.

Let’s talk about all pitchers that throw more fly ball out pitches than ground outs. Batters who can extend their arms can hit for more power. If pitching up in the zone is routine then pitching in needs to be part of that routine, jamming hitters will produce pop up outs not home runs. Change ups are great pitches when used properly, and if Anderson has a 10 mph differential with his fastball and the control to throw the change up for strikes he has a winner.. The same goes for sinkers. Those pitches tend to be located down and away, when coupled with an ok but not over powering fastball thrown up and away you get Chase Anderson’s dilemma. Pitching his so so fastball up and in will improve his entire pitch palette. A stat I don’t often see quoted here is hit batsmen. In this instance more would be better. That is not to encourage head hunting but rather to take control of a bigger part of the plate. Should you go back to the days of Bob Gibson, Don Drysdale, Sandy Koufax, etc. power pitchers lived inside without good sinkers or change ups like Anderson. It is worth a try because the difference between 2 seam versus 4 seam fastballs to big league hitters is nothing.

That all makes sense to me. I recommend the three pieces about Anderson’s change linked in the piece above, especially the Eno Sarris one. Tremendous, and I think you’d enjoy it.

Also, I’m totally with you about the merits of pitching inside:

http://insidethezona.com/2015/01/pitching-inside/

[…] Inside The ‘Zona likes Chase Anderson‘s decision to throw more sinkers. […]

[…] Anderson: High hopes for Anderson this year, especially since his contemplated increased reliance on his sinker seems like a good idea. Anderson threw 127.1 innings in 2012, 88 (partly in relief) in 2013, and ramped all the way up to […]

[…] Anderson is projected to be the D-backs’ best starter this year, and considering that his planned increased reliance on his sinker is likely to have positive results… there really shouldn’t be any obstacle too big for Anderson to be the guy. Even if it […]

[…] he was going to try to keep the ball out of the air by throwing more sinkers, and that was and is a very good idea. But unlike Hellickson — he’s not. Anderson got by throwing the sinker 21.20% of the […]

[…] spring training, Anderson was working on making the sinker a more pronounced part of his arsenal. In 2014, he had let up a whopping 16 home runs in his 114.1 innings, averaging nearly one per […]

[…] early March, Chase Anderson announced a change to his repertoire; he would commit to his sinker, and start trying to throw his curveball in the zone (generating […]