D-backs Sport High Replay Challenge Success Rate, But Should Aim Lower

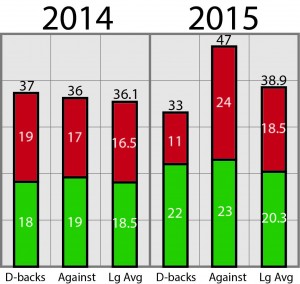

If you’re like me, you’ve gotten used to our brave new world of replay challenges. In the two seasons since replay was expanded, 2,664 challenges have been leveled by managers over that span, 1,268 of them successful (47.6%). It’s part of the fabric of the game now, but not of every game; in those two seasons, the D-backs have made 70 challenges, about one every fifth game or so. Two or three times per month, though, the D-backs have had a ruling on the field overturned — and that puts replay challenge right in the middle of all of those little things we look at in the game, where there are small but definite and measurable differences.

In one way, it’s easy to keep score of this battle: the D-backs have had 42 ruling overturned against them, just barely more than the 40 D-backs challenges that were successful. But we can do better, can’t we?

There are many pieces to this puzzle. As a team, you want your manager to have as much of the right information as he can; but he’s not in the video room, and while he has his own eyes and those of his team at his disposal, it’s not like he gets to see the clips that umpires would be reviewing, from every angle. And that’s an important part of it: the question isn’t just whether the right call was made, but whether the right evidence exists to overturn it. Like I believe every other team at this point, the D-backs have someone playing that role in a video room, with feeds that aren’t delayed like those we watch at home.

Beyond that, though, there is strategy and judgment at play. Them’s the rules: each manager gets one replay challenge, and like in football, if you win your challenge, you keep it and can use it again. In baseball, though, there are no time outs to forfeit. If a manager challenges a ruling on the field and is unsuccessful, that’s it for the rest of the game, whether there is only a half inning left to play or whether the team ends up playing another fifteen innings. So that has to be part of it, as well: when do you issue a challenge that seems like a 50/50 proposition, knowing you might really want that challenge later in the case of a more obvious play? As a team, you might decide to challenge in innings 1-3 only if success seems likely, but maybe at the back end of the game, you level a challenge even if it seems like a longshot.

The field general probably considers other factors, too. Is your player really pissed about the call? Maybe you don’t even wait to hear from your video guy — what matters most is backing your player, and waiting for the video guy can only undermine that. Maybe the call was your pitcher trying to make an out at first base, and you think it’s important to get him a breather, or to give a reliever a chance to warm up in the bullpen. Looking like you’re good at handling the situation also has value, even to the team in general; with two outs, a third base coach probably should send a runner even if he feels like there’s only a 40% chance of success, but there aren’t a lot of third base coaches who keep their jobs with 50/50 success rates.

We will never be able to track all of those considerations the way a manager can and does, and without them, it’s hard to brand someone good at making the decision or bad at it. Sticking with the third base coach: if he did have a 50% success rate in sending runners, you’d suspect he wasn’t very great at his job, but you would want to look at each individual play to figure out what happened. Heck, you might want him debriefed after every game: what was he thinking? If you did that, you’d start to get a feel for how accurately the coach understood the break even points for each play. If he did understand them and still looked poor, the problem might be reading the situation in the first place.

Still: the D-backs had the second-best success rate in all of baseball this year with replays, issuing 33 challenges and overturning 22 calls. The only team to do better with the replay crew in New York: the Yankees and manager Joe Girardi, who had a 75% success rate a year after an 82% success rate. In looking from team to team, though, two strong trends emerge: the more challenges issued, the lower the success rate (okay, that one’s obvious); and also, the more challenges issued, the more overturned (okay, that might be more obvious).

Other some of those human element issues, the only downside for losing a challenge is not having no chance of winning one later. On one level, that’s like saying “I could eat this sandwich, but then I wouldn’t have a sandwich.” Why else would you have a sandwich? If it’s me in the dugout, while I’m weighing all of those things, I want to know just how likely it is that I’ll regret losing my challenge. Just one piece of that puzzle, but one that we can use data to get a very solid base of knowledge.

Teams have played 9,720 games in these two seasons (real number of games is half that), and 1,166 calls have been overturned. So it’s something like one play getting overturned per team per nine games — or a 12% chance of getting a play that would be overturned if you challenged it. Halfway through a game, in deciding whether to challenge a particular play, the risk of not having the challenge later if you need it would seem to be pretty low.

It is, but not quite as low as 6%. If we’re right that there is strategy at play here, then there were some plays that a manager would have challenged if he still had one to use; and if managers have been conservative in using their challenge, maybe there were a whole bunch of longshots that actually would have worked out. We’re talking thousands of games, here. The average manager has challenged in about 20% of his games, but I can’t say “go for more longshots” without noting at least that there’s a chance that later in the game, there’d be another play that the manager wouldn’t ordinarily challenge — and yet was a stronger bet than the one earlier in the game.

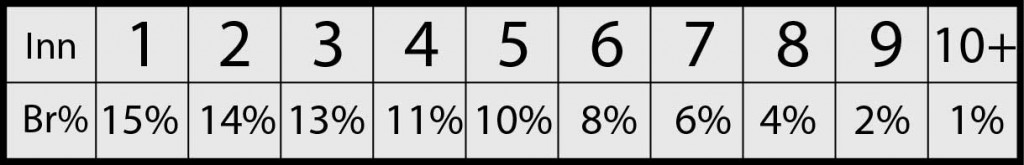

Just guessing, then, that if we lower the threshold for what should get challenged in general, the team’s chances of getting a reviewable play in a particular game are more like 15%. So if you’re considering whether to review the first play of the game, what you’d want is a chance of success better than 15%; and yet if it looks like a 20% longshot, that chance of another play later in the game is not necessarily a reason to rule it out. Break even points would look a little something like this (and this is just back of the envelope):

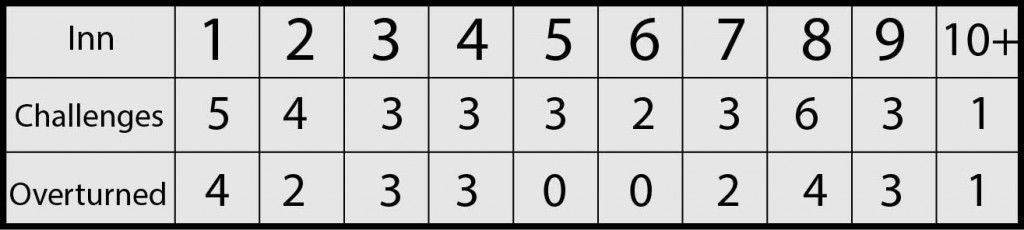

Compare to what the team actually did this year:

Basically, while I don’t have a feel for how many reviewable plays are out there on a game-by-game basis, the threshold for reviewing is probably lower than the team has treated it this year. The innings where the team got closest to what may be the right break even rates are actually innings 5 and 6 — those aren’t black marks, they’re totally okay. It’s a little weird that the beginning of the game had more reviews than the middle — the number should slowly crescendo through the innings — but we’re talking about samples so tiny here, and the plays that lend themselves most obviously to replay are randomly distributed.

There really are lots of factors at play here. But as boring as it is and so long as the team doesn’t pay some kind of other price, the risk of losing the opportunity to challenge later just doesn’t seem to affect the decision that much. If there’s a chance of reversal — even if that chance involves a view of the play that the D-backs Video Guy just didn’t get a chance to see before the decision is made, etc. — it’s worth going for it. We can applaud the D-backs for their very high success rate with replay challenges this year. But as the bar graph at the beginning of this piece suggests, that doesn’t mean they won much more than the average team — it just means that they wasted less time.

One Response to D-backs Sport High Replay Challenge Success Rate, But Should Aim Lower

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Old friend alert https://t.co/6X2Su6PKrf, 9 hours ago

Old friend alert https://t.co/6X2Su6PKrf, 9 hours ago This is going to be fun and I hope you join us! #Dbacks https://t.co/YWfD7ymupf, 10 hours ago

This is going to be fun and I hope you join us! #Dbacks https://t.co/YWfD7ymupf, 10 hours ago RT @TheRattleAZ: 🚨 LIVE VIDEO SHOW TOMORROW AT 7 PM 🚨

Join @OutfieldGrass24 and @JesseNFriedman tomorrow night at 7 PM for a… https://t.co/E9X6m7HeUV, 10 hours ago

RT @TheRattleAZ: 🚨 LIVE VIDEO SHOW TOMORROW AT 7 PM 🚨

Join @OutfieldGrass24 and @JesseNFriedman tomorrow night at 7 PM for a… https://t.co/E9X6m7HeUV, 10 hours ago Disgusting. Absolutely disgusting. https://t.co/xIPKxM4viX, 10 hours ago

Disgusting. Absolutely disgusting. https://t.co/xIPKxM4viX, 10 hours ago RT @cdgoldstein: What are minor league teams doing to make a mark on their community without a minor league season? @OutfieldGrass24… https://t.co/4Kp6mVa0eC, 11 hours ago

RT @cdgoldstein: What are minor league teams doing to make a mark on their community without a minor league season? @OutfieldGrass24… https://t.co/4Kp6mVa0eC, 11 hours ago

Powered by: Web Designers

[…] D-backs Sport High Replay Challenge Success Rate, But Should Aim Lower […]