D-backs No Longer Winning the Base Running Race

When you think of base running, the first thing that comes to mind is usually stolen bases. Of course you want to avoid any and all TOOTBLANs (Thrown Out On The Bases Like A Nincompoop), but steals are front and center. As long as guys are getting around alright, this just isn’t something that often under the scrutiny of fans. We all remember Gerardo Parra getting thrown out all the damn time and we can also recall those critical bases that Ender Inciarte used to nab. You probably know that Paul Goldschmidt is a sneaky base-stealer when the time is right, but really, beyond that, how much do we think about base running from game to game? Not a whole lot.

Part of that is because baseball ebbs and flows and if there’s a terribly slow pitcher on the mound or a rookie catcher behind the plate, any team can look like base stealing machines on occasion. But what about all of those other games when things just look “normal?” Truth be told, there’s a lot of data coming from those games and many opportunities take an extra base on a single hit to right field or just avoiding hitting into an inning-ending double play. Those things matter, too. In fact, because they happen all the time, they matter a lot.

Let’s compare a couple of simple situations. Let’s say there’s a runner on first with one out. The batter steps in and there is, on average, .509 runs scored in an inning with this kind of situation. The next batter singles to right. If the runner gets to second, we have runners on first and second with one out and the average runs scored jumps to .884. If the runner from first takes the extra base and gets to third, the run expectancy jumps again to 1.130. At this point, we’ve more than doubled the expected number of runs score in the inning before the batter even saw a pitch with a runner on first. If that batter had grounded into a double play, well, you’re good enough at math to know the run expectancy drops to zero and the inning is over. If you smell what I’m stepping in, you understand that this one at-bat, the one with a runner on first and one out (which occurs all the time), is a critical one.

There are a bunch of ways to calculate the whole event and the best is RE24. We’ve written about that stat here in the past, but if you need a refresher, take a peak at the FanGraphs Glossary. In the scope of this work, however, I’m interested in the base running component. Are the runners taking that vital extra base? Are they stealing bases? Are they avoiding those dreaded double plays that make us moan and groan?

Fortunately, there’s an app stat for that. FanGraphs bakes a holistic base running component baked into their WAR calculation and it goes by the abbreviation of BsR (for, you guessed it, base running). BsR takes three things into account: stolen bases, running the bases (taking extra bases when the opportunity arrises) and double plays hit into/avoided. Nearly a third of the way through the season, the Diamondbacks have fallen on hard times in this segment of the game.

Last season, the D-backs were the third-best team in baseball by BsR behind just the Rangers and Cubs. This year, they’re 12th in baseball, clustered right around average with the Rays and Athletics, two teams that don’t necessarily scream “team speed” outside of maybe Kevin Kiermaier and Billy Burns. Losing key personnel in A.J. Pollock and Ender Inciarte hasn’t helped, but Chris Owings shares the team lead in steals (6) and isn’t a big downgrade. So what gives?

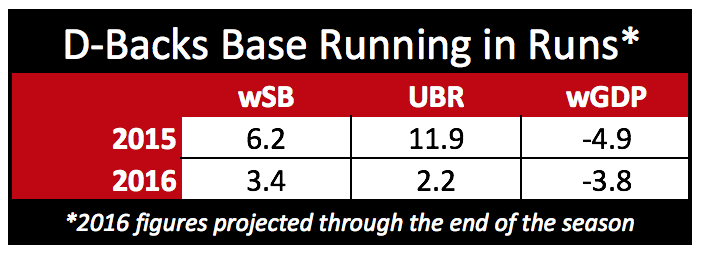

Arizona was stellar in 2015 thanks in large part because of the Ultimate Base Running (UBR) component of BsR. This accounts for those extra bases taken, upping the run-scoring in a big way as our previous example highlighted. They haven’t been nearly as productive in this arena in 2016 and we have to wonder why? Is just missing a speedster or two in the lineup and on the bases? The team is cumulatively slower even by the back-of-the-envelope math, but this could be a result of just where balls have been hit, what types of hits have been delivered with men on base, or maybe a more conservative approach by Chip Hale and Matt Williams not wanting to make any unnecessary outs. In essence, there’s a lot of noise here, but the end result is killing some production.

The stolen base numbers (wSB) are down by about half and maybe that’s where you attribute the loss of two fast outfielders, only one of which has been replaced. Inciarte started in place of Yasmany Tomas a lot last season and basically played with his hair on fire all the time, so this is a little more intuitive. Nick Ahmed can swipe a base on occasion, too, but he’s hardly ever on base to start with. Jean Segura has missed some time and perhaps an extra steal or a couple of extra advanced bases would’ve skewed the numbers a bit more in Arizona’s favor. All told, however, the opportunities for steals, both in terms of being on base and who is on base is showing through some. The double play component (wGDP) is actually up a little, but the team is still below average in double plays grounded into/avoided. That’s been the case for a little while and although it’s certainly not good, it’s not the cause for the team’s plummet in BsR in 2016.

It’s still early and there’s time for the Diamondbacks to make up ground, but the early returns on the bases aren’t good. It’s gone from being a sneaky team asset to just okay in just a couple short months. It’s also a place where the team couldn’t afford to lose any value if they were going to head to the postseason, something that seems more and more like a distant dream as they’ve fallen 8.5 games out in the division. By the end of 2016, their drop in base running production could cost them something like a win-and-a-half in the final standings compared to last year. In a season when nothing has gone right, the team may be better off going for broke on the bases and pushing opposing defenses to make difficult plays. Driving the bus should apply to running the bases, too.

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04 RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Tarik Cohen is so fast he just tackled himself, 47 mins ago

Tarik Cohen is so fast he just tackled himself, 47 mins ago RT @JCGonzalezOR: Special thanks to @HillsboroHops for hosting a LatinX community outreach and visioning session. This organization i… https://t.co/OxmEgwOpEh, Dec 08

RT @JCGonzalezOR: Special thanks to @HillsboroHops for hosting a LatinX community outreach and visioning session. This organization i… https://t.co/OxmEgwOpEh, Dec 08 Old friend alert https://t.co/xwSHU0F8Hn, Dec 08

Old friend alert https://t.co/xwSHU0F8Hn, Dec 08 Every once in a while you get a beer that's just a little off... Usually happens to me at airports., Dec 07

Every once in a while you get a beer that's just a little off... Usually happens to me at airports., Dec 07 If Pollock doesn’t sign with a team that wears red uniforms I’m going to be really disappointed. Working theory: Se… https://t.co/zHn9DqzEiD, Dec 07

If Pollock doesn’t sign with a team that wears red uniforms I’m going to be really disappointed. Working theory: Se… https://t.co/zHn9DqzEiD, Dec 07

Powered by: Web Designers