Forfeit if the Pirates Throw Another Headhunter Pitch

We’re still waiting to hear that Jean Segura is all right after he was beaned in the 7th inning last night by the Pirates’ Arquimedes Caminero, but Caminero didn’t wait long to pitch high and inside again — in the 8th, he caught Nick Ahmed in the jaw with a pitch that glanced off the top of Ahmed’s shoulder. Those links are to the clips, but just in case you don’t want to see it: Segura tried to duck, and that pitch caught a lot of the front of Segura’s helmet. The pitch to Ahmed, though, was on its way to his face so exactly that all he could really do was roll with the punch.

There’s a lot more context, of course. In between those two Caminero HBPs, Evan Marshall threw high and tight to David Freese, hitting him in the front of his shoulder. And it wasn’t all that long ago that then-Pirates reliever Ernesto Frieri cracked Paul Goldschmidt‘s hand on August 1, 2014 — with Randall Delgado hitting Andrew McCutchen in the back the next day. The Pirates generate these situations. No, they don’t hit anyone on purpose, necessarily. But it’s not all that different if the beanballs come because of something else that’s being done on purpose — at that point, it’s not just callous, it’s calculated. And the D-backs have a limited number of ways to respond.

Still Pitching High and Inside

Nobody wants to see a beanball war. As Tony La Russa told Nick Piecoro in 2014, pitching up and in has “rewards,” but also “risks.” At FanGraphs, Jeff Sullivan did the research to back up TLR’s assertion that the Pirates were pitching far inside much more than the average team. At that point in 2014, the Pirates were leading baseball in inside fastballs with around 3,300 — ahead of the next team by around 600. The Pirates still pitch high and inside; using the “zones” from PITCHf/x, 8.76% of their pitches since the beginning of 2014 are fastballs in the high/inside quadrant of pitches high and inside to the batter. No other team has a percentage higher than 7.69%.

And that’s meant hit batsmen. Since the beginning of the 2014 season, the Pirates have hit batters 182 times, well ahead of the second-place team (Reds, 151) and the MLB average (123.3). That may not sound like a lot, but every other team is packed a lot tighter around that MLB average. In fact, every last one of the other 29 teams have a HBP total within 1.5 standard deviations of that average, above or below — the Pirates are the sole outlier, more than 3 standard deviations above the average. And the Pirates are one of those teams.

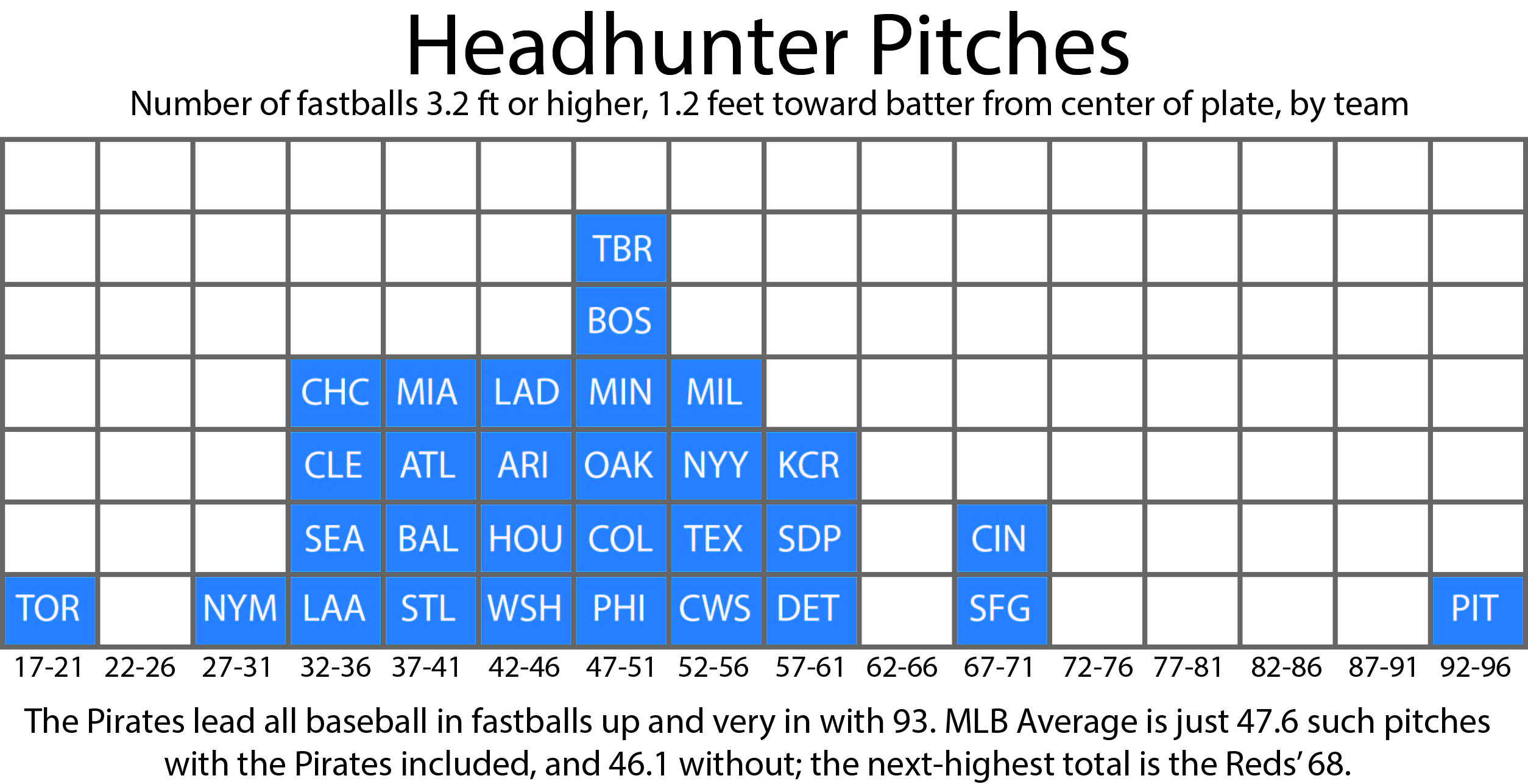

I’m not all that concerned with inside fastballs or HBPs, specifically. This is about the threat of high HBPs — the balls that can find a batter’s head, arms, hands. Looking for those pitches, I pulled all fastballs this year that were at least 3.2 feet high and 1.2 feet in on the batter from the center of the plate (the rulebook zone ends at 0.7 feet inside). We’ll call them Headhunter Pitches. And in terms of Headhunter Pitches this season, the Pirates are far, far out in front of the rest of baseball: they’ve launched 93, double the average of the other 29 teams (46.1). No other team has thrown more than 20 Headhunter Pitches above the average, and the vast majority are within 10 or 11 of the average.

The Pirates’ Depraved Indifference

Were all 93 of those Headhunter Pitches meant to hit someone? Of course not. Each one of them could have, though. The Pirates are rolling dice, and from a purely objective standpoint, if they think it makes their pitching a lot more effective, isn’t it a great idea? Sure, they put an extra duck on the pond from time to time, but the Pirates must think the benefits outweigh that downside. And yeah, some players could get hurt. But they won’t necessarily be Pirates.

Forgive the extreme illustration here, but there’s no replacement for it. If you try to kill someone and succeed, with very few exceptions, you’ve committed murder. If you act recklessly knowing you’re putting lives at risk and someone dies, you may have committed manslaughter, a less serious crime. But if you aim a gun at someone’s house and shoot, knowing they’re inside — that shot might not be especially likely to hit someone, but if you do kill someone that way, that can also be murder. Sometimes, no distinction is made between “on purpose” and “doing something that might mean the other thing happens.”

I’m not a criminal attorney, and nothing I write on this site constitutes legal advice, and you shouldn’t take it as such. The point is that sometimes, recklessness is indistinguishable from intent, and that sometimes, recklessness should be treated as the same as intent. When it comes to the playing field, things get very complicated, legally. Acts that could put a person in jail or at the wrong end of a civil judgment in everyday life are completely acceptable when two or more people are playing a contact sport. My point isn’t that the Pirates or Caminero should be held accountable in a courtroom if Segura was seriously hurt last night; my point is just that this isn’t business as usual, and it shouldn’t be treated that way. There are risks to the Pirates’ approach, and the risks probably shouldn’t all be felt by opposing teams.

Retaliation Isn’t Working

The public D-backs bluster in late 2013 and 2014 about retaliation had a purpose. Retaliation HBPs are meant to deter other HBPs, at an uncertain time and place somewhere down the road. Don’t mess with us; you’ll get messed up, too. And while the D-backs’ public comments on retaliation were not exactly well received, they did help accomplish that purpose, because the whole point is to send that message. Heck, doing it with public comments might be more effective than letting a pitcher do the talking on the field, and it has the added benefit of not actually hurting anyone.

But let’s get back to last night’s game. When Caminero hit Ahmed in the 8th, he might have been thrown out of the game even if there were no warnings in effect; home plate umpire Larry Vanover was clearly affected by the Segura beanball, signaling immediately to the D-backs dugout in a way that seemed panicked. That only became a sure thing, though, after warnings were issued. Let that sink in.

Marshall did hit Freese in the bottom of the 7th, but the result was that official warning. Marshall’s pitch wasn’t just a deterrent in an abstract sense, a message to all teams meant to be heard the rest of the year; it had an actual effect on the game, which led to an actual outcome. It should have made Caminero and the rest of his club less willing to pitch high and inside. But possibly thanks to the Marshall HBP, there was not going to be a third HBP by Caminero in that game last night. As incentives go, that’s perverse. Letting this kind of dispute get worked out on the field this way endangers players; the question ends up being whose players will get hurt.

Promises of retaliation aren’t working. Thanks to the combination of unbalanced schedules and interleague play, the D-backs play the Pirates about as often as they play the Astros; they’ve faced off against the Pirates just 11 times since Randall Delgado drilled Andrew McCutchen in retaliation for the Goldy injury. And the whole retaliation thing is kind of a baseball unwritten rule. Other teams may not be as outspoken about it, but the risk for retaliation is still there for the Pirates, 162 games a year. And they’re still pacing the field in Headhunter Pitches by a large margin.

What Can the D-backs Do?

The D-backs could just hope for the best, here. Or they could make a threat that the Pirates will listen to. If they could take away the Pirates’ desire to pitch high and tight, that would be something. A warning instituted before the first pitch is thrown could do that, maybe; getting a starter tossed early causes problems that getting a reliever thrown out does not. The problem: it’d be problematic for the D-backs, too, if Rubby De La Rosa risked getting tossed early in the game. And the Pirates pitch first. The only way to do that might be for Chip Hale to make some very explicit and incendiary threats before the game, and even that might not work, or cause a host of other problems.

The only workable solution I can think of is to threaten to forfeit, or to actually forfeit. If the Pirates are going to continue to pitch high and tight on purpose, knowing an unconscionable number of Headhunter Pitches are a likely consequence, they are recklessly endangering players’ lives and careers. One key injury for the D-backs this season could have enormous consequences, and not just for this season. More than most teams, the D-backs are committed to a Contention Window in the medium term. More than most of the teams in that situation, the D-backs don’t have extra position player talent to burn; there may only be one or two players in the minors right now who have the potential to be average major leaguers within the next two years. Why risk it? If both Segura and Ahmed had been incapacitated last night, where would this team be? The team is stretched thin — and may not be able to afford the price of acquiring another decent player.

In 1977, the incomparable Earl Weaver was managing a game in Toronto when a “light rain” began to fall during the game. To keep their bullpen mounds dry, the Blue Jays covered them both with tarps (and not Baltimore’s). To keep the tarps in place, they used bricks. And that was too much for Weaver, who refused to keep playing in the fifth inning unless the bricks (and then) tarps were removed from the bullpen area, which was in play. From the Chicago Tribune:

Weaver insisted on the hazard’s removal. When umpire Marty Springstead refused to order that it be done, Weaver called the Orioles off the field.

“I might have saved someone’s career,” Weaver said. “There’s only four feet of space between the foul line and the mound. I had a guy slip out there last night and wasn’t about to let it happen again. If you can’t go four feet and catch a ball, there’s something wrong.

“I can’t afford to tell my players not to go after a foul ball in that area. Mora [Andres] almost broke his leg on that damned thing yesterday. If that had not happened I might not have thought of it. If a guy slips out there and hurts his leg, how am I gonna feel?”

Weaver apparently hoped to have the game resume on a different date that September, but because he didn’t protest the game, the league president couldn’t reverse or alter the umpire’s decision that the game had been forfeited. Reportedly, another umpire had advised Weaver during the game that he could play the game under protest, but Weaver declined because he “value[d] the safety of [his] players.” Playing an unsafe game to successfully protest that it’s unsafe doesn’t make a whole lot of sense.

And the same is true for the Pirates’ pitching habits. After last night’s game, Chip Hale noted that he couldn’t get in Caminero’s head — but that if he wasn’t trying to do it, he shouldn’t be pitching in the majors (video, includes the HBPs). Why? Because it’s unsafe. But Caminero is just one of several pitchers who may hay by pitching high and tight, and who throw Headhunter Pitches; even if you remove his 7 Headhunter Pitches from the Pirates’ totals, that team is still a wild outlier. If it’s unsafe for the D-backs to get in the batters’ box against Caminero, it’s unsafe for them to bat against the Pirates unless the Pirates back off their high and tight strategy.

Tonight’s starter Jeff Locke has thrown 11 already this season; tomorrow’s starter Gerrit Cole has thrown 11. One injury could be significantly more costly than a 0-9 official score from a forfeit, and if the Pirates continue their business as usual, the D-backs could end up regretting the decision to take the field. Should they forfeit both games right now? Of course not. But if threatening to forfeit before the game doesn’t result in some different pitching habits in the game, Hale should strongly consider pulling his team the way Weaver pulled the Orioles that day in ’77. In the words of Frank Underwood, if you don’t like how the table is set, turn over the table. Let’s see how the Pirates like dealing with fans who only get to see a fraction of a ball game tonight, and dealing with a mostly empty ballpark on Thursday.

23 Responses to Forfeit if the Pirates Throw Another Headhunter Pitch

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Bring back WJLR Justice League Radio, 23 hours ago

Bring back WJLR Justice League Radio, 23 hours ago RT @Beervana: Oregon legislators introduced a new beer tax that would make the state’s beer the most-taxed in the country—at a le… https://t.co/pHZtnsTgM7, Feb 26

RT @Beervana: Oregon legislators introduced a new beer tax that would make the state’s beer the most-taxed in the country—at a le… https://t.co/pHZtnsTgM7, Feb 26 RT @ZHBuchanan: "This happened to me, what can I do with it? I can help people."

Meet Jill Gearin, one of the few women calling Mi… https://t.co/irdUR9xsrS, Feb 26

RT @ZHBuchanan: "This happened to me, what can I do with it? I can help people."

Meet Jill Gearin, one of the few women calling Mi… https://t.co/irdUR9xsrS, Feb 26 Old friend alert https://t.co/qVSKpR6k3T, Feb 23

Old friend alert https://t.co/qVSKpR6k3T, Feb 23 RT @Mike_Ferrin: I'm discussing “Baseball talk ”. Today, Feb 23 at 2:00 PM MST on @joinclubhouse. Join us! https://t.co/Csag08Iy7B, Feb 23

RT @Mike_Ferrin: I'm discussing “Baseball talk ”. Today, Feb 23 at 2:00 PM MST on @joinclubhouse. Join us! https://t.co/Csag08Iy7B, Feb 23

Powered by: Web Designers

I am in total agreement. Something has to be done, the risk of potential injury far outweighs the cost of losing one ballgame. And retaliation means nothing to the Pirates. Apparently it will take something as drastic as a forfeit for MLB to decide the Pirates are playing a dangerous game. Pitching at heads is far more dangerous than hard slides at second, or home plate collisions.

How about just issuing warnings before EVERY Pirates game?

Thanks, and that’s a pretty good idea. You can’t technically protest based on an umpire’s ruling that is considered a judgment call, but how about demanding that warnings be issued at the outset of the game, and then playing the protest if the umpire doesn’t comply?

I do think warnings probably work early in the game, when the penalty is needing to piece together 6-9 innings with a bullpen. But it might not be as effective later in the game.

Provocative idea and some quality numbers to back it up. My only thought was to hit first. That would bring out warnings much faster and cause the Pirates to pay the price after warnings are issued. Plunk a few guys in the butt and anything that Pittsburg does looks a whole lot different. I’m with you and hope that the dbacks don’t take the field today… Sadly but I’m sick of waiting for the plunking my dbacks take from these guys.

Warnings right away to start the game does seem like it would help, definitely. With no margin for error, much better chance of playing nice…and of getting runs on the board.

I don’t think hitting first is the answer. The warnings weren’t issued last night until the second hit batsman. And also, for the vast majority of fans and media, who don’t have (or don’t care) about the above data, the DBacks would again be branded the “bad guy” instigators, just as in 2014.

MLB has made changes to protect players in other situations. This also needs MLB sanctions. If pitcher hits batter above the shoulders, regardless of intent, the pitcher AND the team should be fined. Pitchers and coaches will learn to control their pitching if $$ is involved.

“Perceived overemphisis on throwing inside” is a quote from a Sporting News article on TLR’s reaction. “Perceived”? Doesn’t any other teams care about this? Do they have to seriously injure somebody first? How exactly is a broken leg at second base different from a broken hand or fractured jaw while batting?

What went into your choosing of the seemingly arbitrary numbers of 3.2 feet high and 1.2 feet in. Also, 3.2 feet high does not really seem “up and in”. Having a hard time picturing this. Is that 3.2 feet from the bottom of the strike zone? from the ground? from the middle of the strike zone (halfway between knees and top of zone?)

Also, if you adjusted the numbers a little, say 2.8 feet high, does that fill out the differential? Or say 1.0 feet inside.

He said where 3.2 feet was from in the article…

“Looking for those pitches, I pulled all fastballs this year that were at least 3.2 feet high and 1.2 feet in on the batter from the center of the plate (the rulebook zone ends at 0.7 feet inside).”

Actually, no he didnt reference the starting point for the 3.2 feet high.

He referenced that the rulebook zone ends 0.7 feet inside and that it was from center of plate

If 3.2 high starts from the ground center of the plate, than its seems way too low.

I guess you’re right, he didn’t explicitly say from the center of the strike zone and instead said from the center of the plate, but I’m going to take that leap for him since most batters aren’t 4 feet tall.

Alan — my goal was to zero in on pitches for which there was a higher likelihood of serious injury. Sure, the Pirates pitch more inside in general — but I just don’t care as much about pitches in the thigh, and most hitters can dance when the ball is lower than that. Up above center of mass, there’s just not enough time within the 0.4 seconds to the plate to recognize the danger and get the whole body out of the way.

With that goal in mind, I also didn’t want to cherry pick. So I looked up the two pitches from Tuesday and the one that broke Goldy’s hand, wanted to leave some area around that, too, for a kind of “Risk Zone.” That might have been a better term to coin than “Headhunter Pitches.”

3.2 high from the ground, yes. But note, the one that hit Segura in the head and sent him to the hospital was 3.5 feet.

If I was too generous with the definition, it probably wasn’t in height. The plate is 17 inches across, so -0.7 or so is the edge of the plate inside for a right-handed pitcher. -1.2 seemed like a good number for that reason, but, truth be told — even though HBPs seem to start around there and pick up, that might include some pitches for which a batter turns into it on purpose. That wasn’t really what I was after. And the one that broke Goldy’s hand was farther off the plate, -1.77.

Alan, on your other point of whether 2.8 would fill out the differential, to be honest, I didn’t test more than one set of endpoints. It was pretty time consuming to combine every team’s results (lefties had to be done separately, obviously). I did look at past years briefly to see if this year was especially fluky; seemed higher this year, but not out of line.

All I have at the moment to allay your concern is the overall HBP numbers since 2014 — and I did run the numbers based on “zone” (as defined by PITCHf/x). I used “11” for RHH, “12” for LHH, and those are big — they include pitches directly over the zone, as well, so long as they’re toward the batter from the center of the plate. And halfway up the zone, to the batter’s side. Basically, all pitches not in the zone that were more high than low AND more in than out.

9.8% of the Pirates’ pitches were fastballs in that location. MLB average (includes Pirates) was 6.9%, 2nd highest total was the Giants at 8.6%. It’s probably the Reds that got the bad rap in the graphic above; they ranked just 8th, at 7.5%.

1.2 feet inside from the center of the plate would be about 6 inches out of the zone (towards the batter), which incidentally is where the batter’s box starts. Let’s use Goldy as an example for the height component. Goldy is 6’3 and crouches slightly in the batter’s box. The 3.2 feet Ryan mentions is about 3’2, or more than halfway up Goldy’s body when he’s standing straight up (and he will lose a few inches crouching in his batting stance). So picture a pitch that is inside the batter’s box and more than halfway up his body.

Reply chain only goes 5 deep, but just adding to my last reply: here are the “11” to RHH, “12” to LHH fastball totals through Tuesday, in descending order. Pasted the corresponding “Headhunter Pitches” totals next to them.

PIT 655 93

SF 588 67

CIN 546 68

OAK 546 50

SD 531 59

MIL 520 55

TEX 512 53

DET 502 58

TB 502 51

CWS 489 52

COL 481 48

HOU 480 42

KC 479 59

LAD 479 44

ARI 478 42

WSH 468 42

MIN 456 50

CLE 452 34

BOS 436 50

PHI 431 48

ATL 417 40

MIA 415 41

BAL 402 39

STL 392 37

NYY 388 55

SEA 374 34

NYM 365 30

LAA 349 33

TOR 337 19

CHC 306 36

The mean is 459, standard deviation 77.23; so based on this (in my opinion) very over-inclusive definition of pitches, the Pirates are still an outlier at 2.5 standard deviations. Giants are at just 1.7 standard deviations, and the Cubs at the bottom are -2.0.

I appreciate the effort you put in. When I looked at doing any separate research to confirm, its daunting. So props for doing that.

I still think 1.2 is kind of arbitrary. IF that truly is the beginning of the batters box line, then the pitch to Segura to start the game is the perfect example. Segura lines up with his feet on or over the batters box inner edge and is hanging on the plate. Any pitcher worth his salt is going to immediately pitch inside to back the batter off. Is that headhunting? I dont think so. Especially when players are wearing front armor now, they hang over the plate, even. But by your standards, the first pitch of today’s game is a “headhunting” pitch. So to me, it fails the eye test.

You also mentioned the Segura pitch. Segura was on the plate in that at bat, and his reaction was to go straight down, instead of back in the batters box, or turn his back to the pitcher. If he turns his back to the pitcher, it hits him in the high arm. Not even the shoulder.

Headhunter pitch seems to be a misnomer. more like upper quadrant pitch.

The goal here was to discuss whether standing in against the Pirates was dangerous enough for a forfeit to make sense. So I’m looking for danger — serious injuries. Guys dodge low pitches often enough, or take it on some soft tissue. But when they do, they aren’t moving their center of mass much, really — hence falling forward if they jump back, etc. I’d stick with 3.2. With your weight on your back foot in that direction, there’s not a lot you can do — 0.4 seconds to the plate and 0.25 to register what’s going on just doesn’t leave time. Turn, sure. But the only way to move your center of mass that fast is to let gravity do the work. I wouldn’t get on Segura for not reacting perfectly.

And — this isn’t the end zone. There’s no hitter who doesn’t cross the “plane” of the batter’s box with a swing. Even in setup, having a body part beyond the batter’s box doesn’t necessarily mean leaning, it just means one’s body protrudes farther than one’s feet, especially coiled for a swing.

The point is the danger, or at least it was for me. “Headhunter Pitch” does not mean headhunter pitch, it refers to what I coined — but I would name it differently if I could do it all again. Especially now that I’ve realized I could have gone with “Danger Zone Pitch.”

You, too, probably shouldn’t get hung up on the one word “headhunting.” And backing the batter off doesn’t have to be done high.

Was the first pitch of today’s game a dangerous pitch? Backing the batter off is capitalizing on fear… if it wasn’t dangerous, it probably wouldn’t work.

Anyway. Never said the Pirates shouldn’t do it, and I won’t.

Beyond the name, the other thing I would have done differently is the inside cutoff. But not by a whole lot. I had a goal, so 1.2 wasn’t necessarily “arbitrary,” and it wasn’t cherry-picked after checking other numbers, either. But it was arbitrary in that it was a guess. It was about halfway between the plate (-0.7) and the pitch that broke Goldy’s hand (-1.7).

Doing it again, though, I’d move to 1.4 inches, as far off the plate as the edge of the plate is from the center. Just ran those totals, but note: this time it’s ALL pitches instead of just different kinds of fastballs, and it’s not a direct comparison to the other list, because it includes an extra day’s worth of games. Let’s call these “Danger Zone Pitches.”

PIT 73

SF 55

BOS 53

CIN 52

MIA 49

NYY 47

ATL 45

TB 45

TEX 45

BAL 44

SD 44

DET 42

MIL 42

PHI 42

MIN 41

CWS 40

OAK 40

COL 39

WSH 39

KCR 38

HOU 36

LAA 34

CHC 33

LAD 32

TOR 31

CLE 30

SEA 29

STL 29

ARI 26

NYM 24

Average is 40.6. That’s still a nice, neat bell curve, plus Pirates. For what it’s worth.

In the above table, the difference between Pittsburgh and #2 San Francisco is 18 pitches. The difference between San Fran and #20 Kansas City is 17 pitches. There’s a 31 pitch difference between #2 and #30, but 18 between #2 and #1. Call it what you want, define it how you want, the fact is that Pittsburgh throws that type of pitche a whole lot more than any other team in baseball.

I might of missed it, but I didn’t see anything about how often Pirate batters are being hit by pitches so I looked it up. In each of the past 3 seasons (2013-15) Pirate batters have been first or second in the majors in being hit by pitches. And so far this season they are tied for 1st.

Including 2016, Pirate batters have been hit more often than their pitchers have plunked opponents in 3 of the last 4 seasons.

This can be interpretted in various ways. One could say that the rest of the league has been punishing Pirate batters for the way their pitchers pitch up and in. Or one could say that Pirate pitchers pitch up and in because

their batters are being hit so often. It’s kind of a chicken and egg thing.

Not really passing a moral judgment in the piece above — the question was whether it was happening to the point that it would be better to not play.

But, no, I think that’s an incredible stretch, that maybe the Pirates are just being targeted by the rest of the league and are responding. If those two things are linked, they’d be linked the other way, too. If it’s the Pirates starting the situation, we have a plausible explanation; but you can’t be right the other way without also being wrong. If the Pirates getting hit is linked to them throwing all these risky pitches, it’s extremely unlikely that it’s also true that other teams’ pitches are not linked to the Pirates’. The Pirates are always the common denominator. You have your answer right there.

Not chicken or egg. Yes, the Pirates get hit more — just like on Tuesday, when Marshall hit Freese. It’s exactly what we’d expect if the Pirates were hitting more batters than the rest of the league, or hitting more in a way that other teams thought mandated retaliation. I’d consider it a confirmation, not an alternative explanation.

I don’t dislike the Pirates, anyway. Let them do them. Just thought the risk of a season-torpedoing injury was high enough to warrant not playing against them.

While I’m not sayting there definitely is a link, I think it’s well within the realm of plausability. For example, let’s say Pirate hitters tend to crowd the plate and take away what pitchers like to think is “Their”

half of the strike zone. Pitcher don’t like that so they try to move batters off the plate by pitching inside, which results in a high number of Pirate batters getting hit or nearly hit. Pirate pitchers would almost certainly respond in kind in order to send a message, “mess with our hitters at your own risk!”.

This may or may not be what is happening, but I don’t think it’s that it’s all that great a stretch of the imagination.

Anyway, thanks for the verty interesting article.

Some enterprising person with lots of time could go through Pirates games and see which team gets hit first. But even if it’s the case that the Pirates are retaliating, you can “send a message” without throwing at people’s heads.

[…] week at ESPN Sweetspot’s Inside the Zona, Ryan Morrison looked into the data and found that the Pirates stand out among the rest when it […]