Should the D-backs Move the Chase Field Fences?

Chase Field is a strange place to play baseball. It’s Coors Field that is widely (and rightly) considered to be the most offense-friendly environment in the game; that’s due in large part to the thinness of the air (less drag on a baseball in flight), but also because it’s one of just two parks in a place with humidity significantly lower than the 50% level used by Rawlings to store baseballs (it hovers around 35%). The latter point is why the installation of a humidor at Coors Field has apparently had some kind of effect. But a humidor would most likely have an even larger effect at Chase, as Phoenix air averages in the 15%-20% range in the summer. It’s not as obvious, but it’s there.

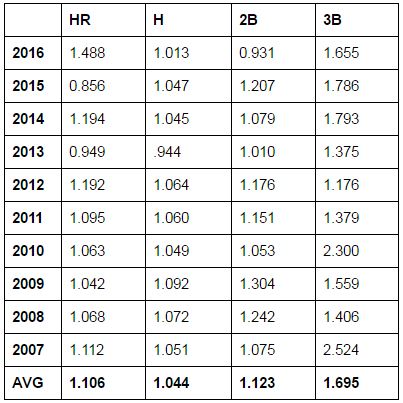

And that’s what makes Chase strange. It’s a large park, which means that even though some distance-inducing traits are there in the environment (Chase is also the park with the second-highest elevation in MLB), that boost to offenses is typically not so much about home runs. According to ESPN’s Park Factors, calculated by comparing Chase stats to the same teams’ performance elsewhere, the D-backs’ home field had a homer-reducing effect last year; it was about 15% below average in terms of home run rate, a factor of 0.856. That’s not true every year, and it’s not unusual for Chase to have a hitter-friendly Park Factor for HRs. Behold:

At the risk of stating the obvious: most hits are not home runs. HRs are just 12%-13% of hits in most years; even if you take them out of the mix, Chase Field’s Park Factor for hits would still be positive. And the park has even more of a double-inducing and triple-inducing effect than it does home runs, overall.

That’s what’s so strange about Chase Field. It’s like the laws of physics are partly suspended; the dimensions of the park are bigger, but the ball travels farther, as well, more than making up the difference. But the human beings doing the fielding are not bigger, or faster, proportionally; they stay the same. At Chase, it’s like teams get the XBH benefits of playing in a large park as in San Francisco or San Diego, but without the normal homer-suppressing effect in response. Push the fences out, and there’s more room for doubles and triples, even as it becomes harder to hit home runs; bring the fences in, and you’d get more home runs, but fewer doubles and triples. Arizona physics suspends that one rule in this instance, in the same way that Coors has more homers, but more of the other types of extra-base hits, as well.

The net result: there’s no obvious way to game the system. A large park might be more forgiving to fly ball pitchers, whereas a ground ball pitcher might be in a better position to enjoy some double/triple-suppressing effects of his outfielders covering less ground without paying an especially heavy home run price. Earlier this season, we wondered if other than extreme pitchers like Brad Ziegler, pitchers who succeeded by managing contact weren’t cut out to succeed at Chase. The type of pitching most immune to Chase is probably the strikeout-heavy kind. Sadly, that’s also the expensive kind. But in that context, maybe the attempts to change pitchers like Shelby Miller look more reasonable. A love affair with velocity certainly is.

So how can the D-backs turn Chase into more of an advantage? On the hitting side, it seems obvious: Chase doesn’t do much for ground balls, so hitters who square up the ball for line drives and fliners look more attractive, even if they aren’t necessarily home run hitters. On the pitching side, the question becomes: can Chase be changed, such that opposing offenses are hurt more than the D-backs are? I can think of just three possibilities.

1. Move out the Fences

In Arizona, a line drive approach can turn into a home run stroke. In 2013, Paul Goldschmidt seemed legitimately surprised sometimes that he put one over the right-center fence; great contact just kind of works. At times, maybe it’s been a little too easy. This season, the team’s homer habits are on the upswing: they have 36 bombs in 29 home games, a pace for 100 or 101 by the end of the season. Last season, they had just 69, which qualifies this season as more than nice (so far).

But they continue to be outhomered at home. Last year, that meant 86 opponent HR to the team’s 69; this year, it’s 42 to 36 (and one of those 36 was a Jean Segura inside-the-park job). That 86 HR total last year? 39 were considered “just enough” home runs by ESPN’s Home Run Tracker, about 10 feet from the relevant wall. The D-backs had just 21. Subtract those from last year’s totals, and the balance shifts: the D-backs had 48 other home runs, to opponents’ 47.

2. Bring the Fences In

You could limit HR by raising outfield walls, but you could also limit doubles, triples and even singles by bringing the fences in. And wouldn’t it be great if Maricopa County paid for a state of the art section of stands in center field that s9mehow didn’t screw with the batter’s eye?

In the one hand, outfield defense does not seem to be a strength for the 2016 D-backs. But on the other, maybe that’s the right situation to want to make the space out there just that much smaller; that might even move Chris Owings to a more conventional depth in center. As things stand, the D-backs can expect to keep Yasmany Tomas around for another 4 seasons after this year, and while David Peralta will almost certainly man the other outfield corner for the foreseeable future, it’s Peter O’Brien who lurks as the Next Big Thing. A somewhat smaller outfield for those guys to patrol does not seem like an especially bad idea.

And on the hitting side, we can’t guess as to the effect the way we can guess on homers with raising the outfield walls. A line drive approach like the ones sported by Goldy, Peralta, and Jake Lamb plays anywhere, though, and as a team, the D-backs seem to average slightly lower hang times on balls classified on fly balls. That means they tend to be more about ‘forward’ than ‘up,’ especially since the team rates well in exit velocity; it stands to reason that the D-backs could see a bigger increase in long balls than their foes, even though making home runs harder to come by might also help the team.

3. Move Some Fences in, Others Out

By now, you’ve probably had the same thought that I had when I started looking at this. The D-backs’ lefty hitters all seem to be pull hitters, at least in terms of long balls; righty hitters like Goldy and Tomas seem to launch balls the opposite way unusually often. So why not make it harder to hit home runs in left field, while keeping RF the same, or shorter?

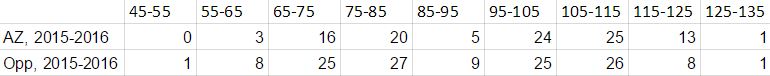

Only in a minor way, if so. I’m probably not the only person to have found the PITCHf/x or Gameday numbers for horizontal angles of balls really frustrating; everything seems to be pushed toward the center more than it should be. Few if any home runs tend to be classified as within 10 degrees of either foul pole (45-55 degrees by the left field pole; 125-135 degrees by the one in right). For Chase Field, though, it’s really almost none, and that may have partly to do with the unusual hitches right by the poles on both sides. Here are the totals from last year:

I’d love it if the D-backs brought in the fence in left-center to expand the Chase Field pool into a more impressive size; the number of pool shots would skyrocket, and random internet searches would lead to our podcast so much more often. Sadly, though, that kind of change might not help, so much. The D-backs definitely hit more of their home runs to left-center, as compared to opponents; unfortunately, that’s not the same thing as saying they actually hit more home runs to left-center. It’s a virtual tie in that area, but too close to call.

Pushing out left field, though — that has some merit. It’s much, much easier to subtract than to add in this context; making the field bigger means actually removing parts of the stands, which is a much bigger undertaking than setting up a new ring of outfield wall as the Mets and Padres have done. We’re also not really talking about a ton of long balls, but the average home run is worth 1.65 runs — if the D-backs were able to manipulate the dimensions of Chase in a way that gave them an advantage of just 5 or 6 extra dingers, that’s the expected equivalent of an entire win.

So, how about it, folks? Would you explore changing the dimensions of Chase Field? If so, would you look to limit homers in favor of other extra base hits, encourage homers at the expense of other hits, or do something a little more nuanced? The D-backs have already built a Contention Window around Paul Goldschmidt. Maybe building his home field around him isn’t the craziest idea, either.

3 Responses to Should the D-backs Move the Chase Field Fences?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Starting 2022 with a frigid dog walk sounds just lovely https://t.co/xoLZSZBpGp, Jan 01

Starting 2022 with a frigid dog walk sounds just lovely https://t.co/xoLZSZBpGp, Jan 01 I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30

I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30 Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29

Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29 Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27

Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27 Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Powered by: Web Designers

[…] Should the D-backs Move the Chase Field Fences? […]

[…] isn’t a whole lot different than the moon. Chase Field is that odd thing, a park that encourages home runs, other extra base hits and hits overall. Noting recent changes […]

[…] randomness – which usually seems to be the actual answer. Chase Field in particular is subject to unique conditions and perhaps several of the players on the team do not fit well into what the park demands. For […]