Time for a Humidor at Chase Field

Once upon a time, the D-backs organization considered storing baseballs in a humidor at Chase Field. The year was 2010, and a mountain of data was available showing the drastic effect the Coors Field humidor had had on Rockies home games. Jerry Dipoto had taken over as interim GM after Josh Byrnes was fired on July 2, 2010, and as Nick Piecoro wrote at the time, Dipoto’s personal experience of trying to pitch at Coors Field impressed on him the potential importance of using a humidor like the one the Rockies had installed in 2002.

Even CEO Derrick Hall seemed open to the idea, calling Chase Field a “launching pad” and examining several ways to help make the run environment at Chase a little less drastic. In that same piece from Piecoro, he quotes Hall:

“We have very young pitching and it looks like that’s our future,” Hall said. “So why wouldn’t we tailor our ballpark to be an advantage there?”

Why wouldn’t they, indeed. In late September of that year, Kevin Towers was hired as GM. In February 2011, Piecoro reported that the humidor had been put on hold. Again from Hall:

“The decision hasn’t been made, but we have no focused on it this off-season,” Diamondbacks CEO Derrick Hall said. “With time running out, it doesn’t make sense to do it this off-season.”

In September, almost four years after his hiring, GM Kevin Towers was removed from his role, eventually leaving the organization. Other than Hall, all of the prominent members of the new front office were not around back in February 2011.

Maybe the first item on the next committee agenda should be re-evaluating whether a humidor would work after all.

Lessons from Coors Field

Although elevation has been a significant factor in the Coors Field hitting environment (the air is only 82% as thick there as at sea level), there isn’t much that can be done about that in Denver, short of installing a roof and airlocks or digging a mile-deep hole in the ground. One thing the Rockies could address was humidity.

Rawlings, the manufacturer of game balls for MLB, stores the balls at 70 degrees Fahrenheit and at 50% humidity. But most MLB cities have a higher average humidity than 50%; Denver’s is around 35% in the afternoons during baseball season. To fully neutralize the effect of the lower humidity, perhaps they would have matched what is normal across the league (in the 60s, although humidity typically dips in the afternoon/evening).

But, 50%. And that makes a difference. Dr. Alan Nathan is Professor Emeritus of Physics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and he’s took a close look at this phenomenon. For a more fulsome explanation of how this works, I recommend this Piecoro piece and a guest piece that Dr. Nathan did for Baseball Prospectus; if you really want to get down and dirty on the science, go to this article co-authored by Dr. Nathan and published in the American Journal of Physics.

According to Dr. Nathan, the difference in humidity between Denver and its humidor accounts for about 2.8 mph in batted ball speed. 0.6 mph of that figure is attributable to the lower weight of a drier baseball; the greater reduction of 2.2 mph comes from the difference in coefficient of restitution (COR). COR is the “bounciness” of a ball; Dr. Nathan uses the word “mushier,” but maybe it’s easiest to think of it as a properly inflated basketball (dry) versus a slightly underfilled basketball (not as dry).

With the help of Greg Rybarczyk and HitTracker (more on that later), Dr. Nathan estimated in the Baseball Prospectus piece that the humidor is responsible for a 30% (plus or minus 6%) reduction in home runs — a figure he later updated to 27.5% (plus or minus 4.3%) in the comments. That comports with the before-and-after data; as Dr. Nathan noted, home runs per game at Coors dropped by 25% after the humidor was installed.

Impact at Chase Field

When he wrote the Baseball Prospectus piece, Dr. Nathan also looked at the potential effect that a humidor might have at Chase Field; this was that same 2010-2011 offseason, and the potential for a humidor in Phoenix was very much in the public consciousness.

You can read the piece to get his “rough analysis,” through which he concluded that the number of home runs at Chase Field might be reduced by 45 percent (error bar of 9%), 1.5 times that at Coors. When he did a more detailed analysis (not published, unfortunately), he concluded that the Chase Field reduction would be 37% (error bar of 6.5%). Last year, 146 home runs were hit at Chase — if we apply that 37% plus or minus 6.5% reduction, that 146 HR figure would get reduced to 92 home runs, or between 82 and 101 home runs (using the error bar).

1.23 times the phenomena at Coors means that at Chase, a humidor would, on average, have a 3.4 mph effect on batted balls. Dr. Nathan notes that the 2.3-percent-per-foot reduction for Coors should remain constant with that at Chase; if both the batted ball speeds and increases in weight follow the 1.23 multiplier, the average distance of what have been home runs would be dropped by 16.2 feet.

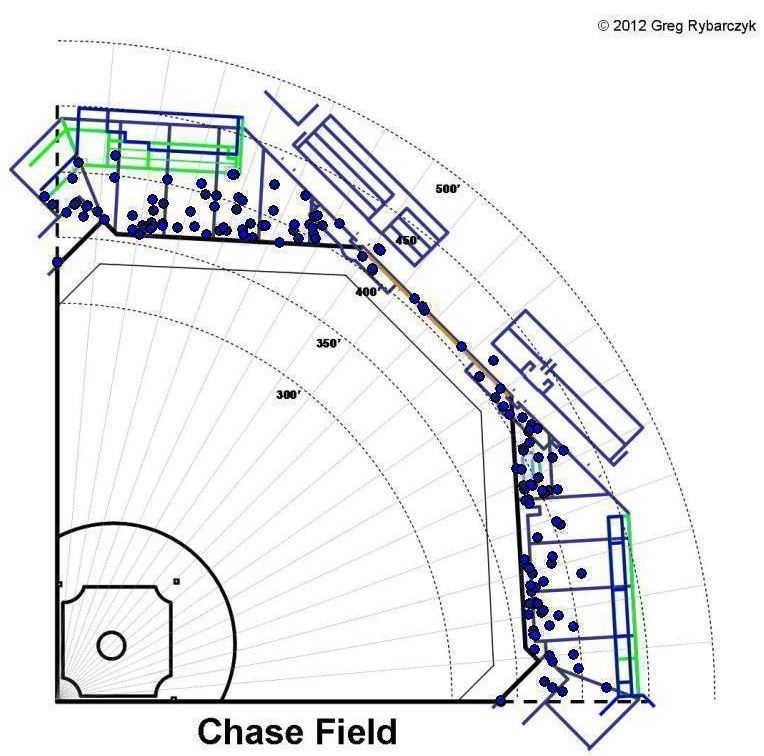

Rybarczyk’s HitTracker is now ESPN Home Run Tracker, and among the great things at Rybarczyk’s site is the classification of home runs by type. “Just Enough” home runs clear the fence in question by 10 feet or less or land within 1 foot horizontally of the wall; at Chase, 51 of the 146 home runs last season were “Just Enough” home runs.

As you can see, though, it’s not necessarily just the “Just Enough” home runs that might have been in play if there had been a humidor. Because of the (varied) height of the walls, we couldn’t extend batted ball distance to turn fly balls into home runs, if, say, we were to try to guess how many bombs there would have been if the humidity of baseballs had been zero. The reverse is possible, however, except in the case of center field home runs that went only as far as the wall but were homers by virtue of hitting it above the yellow line.

What that means is that except for center field, we could draw a new dotted line 16.2 feet beyond the wall and count how many of the blue dots are within that line. I did so with a printout and a highlighter (if you want to repeat the exercise, 16.2 feet is just under one third of 50 feet), and while it’s really difficult to tell what would have happened with respect to some of them, I think the number would have fallen at the low end of Dr. Nathan’s calculations: something like 80 home runs.

By multiple methods, then, we’re guessing that the number of home runs hit at Chase Field would be cut by about one third if a humidor was used.

Does Humidity Linger?

One very big caveat, however. It appears that in the course of his Coors Field analysis and Chase Field rough analysis, Dr. Nathan used the afternoon measured humidity, which is measured at 5pm local time. That’s a pretty good proxy for game time, but as is the case elsewhere, the average humidity in Phoenix is quite a bit higher overall; the annual average relative humidity in Phoenix from April through September at 5pm is 18%, but the morning (8 am) is 37%, and the average (average of all measurements, which are three hours apart) is in the middle: 29%. That suggests that the afternoon measurement is near the lowest point of humidity.

I’m not a physicist, but I suspect that even if you asked a physicist, he’d tell you that the only way to know how quickly a baseball’s humidity acclimates to its environment is to measure that effect in laboratory settings. Still, I sincerely doubt that baseballs used at Chase Field have an average humidity at game time of 23% or whatever the relative humidity percentage is that night. If humidity is always cyclical and if the afternoon or game time is at the low point of humidity, then saying a baseball matches that humidity level is tantamount to saying that a baseball loses or gains humidity exactly as quickly as air. I just don’t believe that.

In fact, it appears that the Rockies started handling their humidor balls differently in 2005, as compared to installation in 2002; they may have stored them longer or removed them closer to game time (again, see the comments to Dr. Nathan’s BP article). The humidor was much more effective after that point; as Dr. Nathan adds in the comments, the Coors Field home runs per game went from 3.20 (1995-2001) to 2.81 in the first years of the humidor (2002-2004) to 2.17 from then until the article was written (2005-2010). I’m not sure whether the effect is linked to the longer storage or the removal closer to game time, but this strongly suggests that baseballs do not lose or gain humidity as quickly as air.

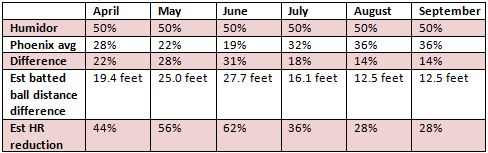

I assume that with respect to a baseball’s humidity, there is some lag. If that’s the case, then the baseballs used at Chase Field might be closer to the average relative humidity than the afternoon measured humidity. It’s probably somewhere in the middle. In most MLB cities, the differences can be 20% or more, so the distinction can matter. But in Phoenix, the difference is much smaller. Here’s what it looks like if we use the average daily humidity (annualized):

That’s a pretty big reduction, no matter how you slice it.

Note: this was based on Dr. Nathan’s calculations for a change in humidity from 35% to 50%. He did slightly change his estimate for Coors Field from 30% HR reduction to 27.5% HR reduction, but I don’t know if that was because he used different data or a different process. It could be that if Dr. Nathan did the figures in the above table, they would get tweaked down somewhat. Also, I’m not sure what he’d say about using daily humidity instead of afternoon humidity).

More Data Up Our Sleeves

I’m sure that the D-backs are way ahead of me on understanding the impact of a humidor, and they can bring some evidence of their own to bear. As Piecoro reported last February, the D-backs paid $15,000 to install a humidor at Reno for use of the Triple-A Aces; the 22% humidity there is much more in line with the humidity in Phoenix than in Denver.

The results? None to speak of. The total number of home runs at Aces Ballpark actually rose from 138 to 142 this year after the humidor installation:

@InsidetheZona 13- by Aces at home: 66; by visitors: 72; allowed on road: 57 14- by Aces at home: 70; by visitors: 72; allowed on road: 49

— Reno Aces (@Aces) November 4, 2014

(By the way: huge thanks to @Aces for that help… they are a must-follow, as perhaps the best-run Twitter account of any baseball team.)

So the humidor didn’t do a whole lot in Reno this year, it seems (although it could just as easily be the case that more would have been hit without it). At the very least, it seems safe to conclude that the number of bombs hit at Reno was not reduced by anything like 37%. That said, the physics strongly suggest that the D-backs would feel some effect if they installed a humidor. Should they do so?

Some Like It Hot

Remember, the humidor was installed at Coors Field to help with their crazy run environment there, but the true culprit was (and is) probably the thin air, not the fact that the thin air was a little on the dry side. The humidor helped solve a problem for which humidity was not completely responsible.

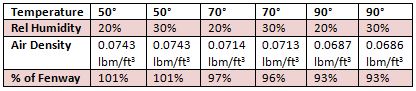

But the D-backs also face a “something extra” problem: heat. Elevation goes a long way toward making the air less dense (Coors air is about 82% as thick as sea level game time air), but heat does, too. Compare Chase Field to Fenway Park. Fenway is barely above sea level (I’ll call it 50 feet), and a typical night game might be played at 70 degrees. In the evening, the humidity might be about 60%. In those conditions, the air has a density of 0.0739 lbm per cubic foot. Compare that to a 90 degree game played at a Phoenix elevation of 1,117 feet and 20% humidity: 0.0687 lbm per cubic foot. The air at Chase Field might be just 93% as dense as that at Fenway. That’s no Coors Field, certainly, but that’s not nothing, either.

Here are some air density data points, all at 1,117 feet elevation:

Not all games at Chase are played at 90 degrees, so it’s probably not fair to say that the D-backs have a full-0n Coors problem, in terms of air density. But they have a nearly half-Coors problem in terms of air density, at least some of the time. They also have a super-duper Coors problem in terms of humidity. The two things don’t cancel each other out and make Chase a second Coors (as we know from experience), but it makes Chase a hell of a lot closer to Coors than to any other ballpark, as far as I can tell.

What Should the Diamondbacks Do?

So far, we have looked only at the effect that a humidor might have on home runs. But that’s not the only potential effect. A more humid baseball is ever-so-slightly larger, and it’s definitely heavier; that might help pitchers pitch. And as Dipoto pointed out to Piecoro (say that three times fast), a dry ball is a lot harder to grip. That might make pitchers less consistent in how their fingers leave the ball, impacting command both in terms of location and in terms of spin. Paging Trevor Cahill.

Not having one’s pitchers try pitching with cue balls could matter a boatload, or it could matter not that much. I don’t have numbers to quantify that. But I suspect that if the D-backs handed their pitchers each two baseballs, one stored in the Phoenix air and the other in a humidor, they would all rather pitch with the latter.

It would be nice if GM Dave Stewart gave a humidor ball and a non-humidor ball a feel test, to find out which one he’d rather pitch with, and how much of a difference he thinks it would make. He would know much, much better than I would. And if it makes a big difference, it might be worth doing even without the HR business.

When Piecoro talked to former GM Kevin Towers in February about the new Reno humidor, Towers said “I kind of like having the offensive edge in our ballpark. I haven’t heard too many players really complain much about having to pitch at Chase.” Seems like a very deliberate choice to me. We do tend to think that offense sells tickets, and this is the same man who had just traded away two promising players for Mark Trumbo, who was arguably likely to be less productive than either Tyler Skaggs or Adam Eaton.

Offense is hard to find. Home runs are very expensive. I think that’s the main reason why the Rockies haven’t tried to go back to the Blake Street Bombers model, after trying just about everything else; they might be in position to take better advantage of hitters with power than the average team, but it’s so disproportionately expensive to pay for that particular flavor of production that in the long run it might not be cost effective for them. But power can work. I get it.

Still — do the D-backs have a team that’s really built to take advantage of that? I could see a humidor affecting Paul Goldschmidt in a big way, but the rest of the team’s hitters aren’t really power guys anyway, or they’re Mark Trumbo, who could still hit his fair share if they started dunking the baseballs in ice water before his at bats.

Pitching and defense may be the way to go for the Diamondbacks, especially considering that defense is typically so, so cheap. I don’t want the team to turn into the Padres, but I’d also like to see the team’s starting pitchers start to do better at home. Last season, the pitching staff had an Expected Fielding-Independent Pitching mark of 3.63, yet it ended up with a 4.26 ERA. Only one pitching staff had a discrepancy between xFIP and ERA greater than that: the Colorado Rockies.

I think the solution is pretty simple. The D-backs should install a humidor. When they do, it should be set to 70 degrees and 50% humidity; I doubt very much that Major League Baseball will allow a different setting. If the D-backs don’t like the results they’re getting from the change, they can simply change the procedure by which the balls are stored, keeping them in the humidor for less time or removing them earlier before game time.

After all, the D-backs have young pitching, and it looks like that is their future. So why wouldn’t they want to tailor their ballpark to be an advantage?

9 Responses to Time for a Humidor at Chase Field

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Starting 2022 with a frigid dog walk sounds just lovely https://t.co/xoLZSZBpGp, Jan 01

Starting 2022 with a frigid dog walk sounds just lovely https://t.co/xoLZSZBpGp, Jan 01 I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30

I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30 Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29

Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29 Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27

Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27 Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Powered by: Web Designers

[…] addition to talking about the possibility of installing a humidor at Chase Field, we talked on Episode 4 of The Pool Shot about some trade rumors, specifically those involving […]

[…] the problem, he can’t be part of the problem anymore. Who knows: maybe the team will actually install a humidor, which could make everything they’ve done thus far seem genius. But the point is: let’s […]

[…] of the doubt in this offseason of change, we could say that hey, this all would make sense if they installed a humidor, and if they traded Mark Trumbo and let Ender Inciarte play. If they did those things, it would […]

[…] plans or Chase Field, something wasn’t working on the pitching side last year. And while a humidor might be the most effective solution to the team’s pitching woes, the departure of Montero […]

[…] fall, I outlined how much of a difference a humidor would make at Chase Field. The difference in batted ball […]

[…] which kind of makes sense anyway. Here, we’ve used the information when trying to determine the extent to which home runs would be reduced through use of a humidor, which was a big help to that analysis (thanks, Greg Rybarczyk and […]

[…] arsenals. Sure, Chase Field isn’t Coors Field, but as we discussed some time ago when it comes to batted balls, the Diamondbacks’ home is the next closest thing to playing at a mile up. Maybe that makes […]

[…] is why the installation of a humidor at Coors Field has apparently had some kind of effect. But a humidor would most likely have an even larger effect at Chase, as Phoenix air averages in the 15%-20% range in the summer. It’s not as obvious, but […]

[…] it by now, even if all you’ve ever done is watch a dozen ballgames. But Ryan P. Morrison has dug into this arena extensively in the past as it pertains to the Diamondbacks, and I’m going to borrow liberally from him. […]