Ender Inciarte, D-backs OF Alignments, and the Run Value of Defensive Replacements

In addition to having some positional flexibility and not being an automatic out at the plate, most fourth outfielders have some kind of “special sauce” that can be particularly useful at particular times, such as great baserunning, being able to hit either righties or lefties particularly well, having some “pop,” or offering not just adequate but very good defense. Some fourth outfielders check more than one of those boxes, but it’s the rare fourth outfielder that has every variety of special sauce.

On Friday’s broadcast, Steve Berthiaume said that Chip Hale viewed Ender Inciarte not as a true fourth guy, but as a “three plus.” What Hale meant by that is starting to come into focus, what with writing Inciarte into the lineup both games so far, and with the maneuver that he pulled last night. Inciarte may get some bonus points for being a pinch-running option later in games, and while research strongly suggests that we can’t bank on him repeating his prolific defensive performance and it may be improperly valued anyway, we can probably still say that he at least checks that box as well. The line that Inciarte blurs, however, is not the difference between a good #4 and a bad one, but rather the line between a #4 and a #3.

What makes this situation unusual is that Inciarte doesn’t necessarily have a particular weakness at the plate; he showed almost no platoon split last year. Inciarte nonetheless fits this roster like a glove as one of the team’s four outfielders; the team features two sometimes-plus hitters with profound platoon splits. As Jeff wrote last week, platooning Mark Trumbo and David Peralta would make a great bet for excellent production out of an outfield slot. What makes Inciarte a great fit as the extra player is the reality of those two players’ splits, not his own. As Jeff noted in that same piece, the reality is that Trumbo won’t see his playing time reduced by much. It’s Peralta to whom Hale has (lightly) handcuffed Inciarte.

The D-backs looked around for a lefty bat in the offseason, noting the roster’s imbalance. Peralta’s tremendous success against right-handers last season could make him that offensive linchpin against RHP starters, with only Jake Lamb in line to help out from that side of the plate. Basically, Peralta is sorely needed against RHP and will probably get the vast majority of those starts. But that’s when Inciarte comes in, quite literally.

How the Moving Parts Fit Together

Here are things we seem to know at this point:

- Inciarte may get playing time against RHP and LHP, and may hit high in the lineup in either circumstance.

- Peralta will start almost every day against a RHP starter.

- Hale will not hesitate to take Peralta out of the lineup if he loses the platoon advantage.

- Inciarte is A.J. Pollock‘s backup in center.

- When A.J. Pollock broke out last year, it was at a time when he and Gerardo Parra protected each other somewhat against platoon disadvantages.

- Inciarte is a good bet to play good defense.

- Mark Trumbo is not a good bet to play good defense.

- Mark Trumbo is likely to get a healthy number of off days against RHP.

Bake those things together, and you get this short-term situation:

Scenario A (RHP): Peralta/Pollock/Trumbo. Once Peralta loses the platoon advantage (or reaches base late in games), Inciarte takes over in left field.

Scenario B (RHP): Peralta/Inciarte/Trumbo. Once Peralta loses the platoon advantage (or reaches base late in games), Inciarte is moved to left, Pollock taking Peralta’s spot in the lineup.

Scenario C (LHP): Inciarte/Pollock/Trumbo. Inciarte or even Pollock could be removed in a double switch if Peralta is used as a pinch hitter (straight substitution less likely).

Scenario D (RHP): Peralta/Pollock/Inciarte. Trumbo may be rested close to once per week to keep him healthy, and this is what his rest days will look like. Depending on their frequency, Hale may or may not use Trumbo as a pinch hitter on these days. If he does, it’s Peralta who is most likely to be removed, Jeff getting a watered down version of the Frankenoutfielder he justified last week.

This works beautifully, I think. Scenario D would be motivated by Trumbo’s needs, but the other three are engineered specifically to cater to Peralta’s platoon split, also providing each outfielder some rest. The only exceptions are likely to come if Pollock or Inciarte (or Peralta) need a true day off, which is something less likely if the time share holds. It’s not going to last for that long, however. When Yasmany Tomas is promoted to the team, it sounds like he’ll be mixing in some outfield time along with starts at third and maybe first. That’s like putting an extra part into this machine, and once that happens, the whole mechanism will need to be adjusted.

For now, however, those scenarios seem to be in place, with Scenario C used on Opening Day and Scenario B employed last night. The fact that it’s Peralta’s platoon split that makes this whole thing tick is what makes Inciarte more than a fourth outfielder. Nonetheless, Inciarte’s main “special sauce” — that defense we were talking about — is what could turn make this time share truly great.

The Potential Value of Defensive Replacements

At this year’s SABR Analytics Conference in March, Greg Ackerman of Syracuse presented the results of a study in which he sought significant relationships between certain types of managerial decisions and the extent to which those managers’ teams out- or underperformed their expected record based on run differential. The only type of decision tested which showed a correlation both positive and significant was defensive replacements. In some small way, defensive replacements help a team win games over and beyond any effect that they have on run differential itself. You can check out the slides from Ackerman’s presentation here (slide 23, in particular).

A likely explanation here is that defensive replacements tend to get used when a team is ahead — and if that team stands a better chance of locking in the score (making it harder for the other team to score, even if it becomes harder for your team to score), maybe the status quo is more likely to stick around. I think it’s not quite like this, but: say you challenged a friend to a coin flipping contest, and you have heads, and the competition is best of 21. You’ve flipped 11 times, and you happen to be ahead 6 to 5. What if you could decide that there would be only 19 flips? Whether it’s 19 or 21, you’re more likely to win (being ahead 1). At 19, however, fewer bad things can happen to you. At 19, that one flip by which you are ahead has a greater chance of affecting the outcome.

Maybe I don’t have that quite right, but either way, we’re talking about a small advantage. And, as Ackerman noted in the presentation, effective use of defensive replacements isn’t all about the manager; the manager has to have a roster conducive to employing them. That’s what Hale has, thanks to Inciarte and the need to at least occasionally treat Peralta as a priority over Pollock.

Defensive replacements don’t just have a chance to affect a team’s win-loss record as compared to its run differential. They can also affect the run differential itself.

There is a disconnect between the defensive side of the game and the offensive one. The former is played every inning, and yet at some positions (including outfield), every position isn’t all that likely to be called on to field in that particular inning. The latter has individual batters coming up in the lineup less than half the time per inning, and yet when a hitter’s spot does come up, he’s definitely going to affect his team’s chances of scoring, good or bad.

Defensive replacements are about locking down the status quo, but they are also about that disconnect between how frequently PA affect the game versus defense. If Peralta reaches first base in the seventh inning, he is not guaranteed another plate appearance in the game. Even if he did, there’d be a chance he’d face a lefty (that’s what the last section is mostly about). But whoever plays in the game in Peralta’s spot may have two or three innings in the field to play before the spot comes up again offensively. That’s how a man like Inciarte (or Pollock) can be particularly useful at particular times.

The question isn’t about how often that player will touch the ball in the field. There are many plays — the majority, at every position — which just about any fielder could make. In our case, Peralta isn’t even a bad fielder, as far as we can tell. So the extra value provided by a defensive replacement (in terms of affecting runs scored or saved) is only about the plays that the replacement (say, Inciarte) would make that the incumbent (say, Peralta) would not.

Let’s stick with left field and Peralta/Inciarte for now. Peralta was horrific in short time in left last year, but better than average in right; let’s call him exactly average. Inciarte rated just above 20 UZR/150 in left and in center; let’s call it 20. For a particular game, we might say that for two innings of Inciarte as a defensive replacement for Peralta, the surplus fielding value is 0.03 runs.

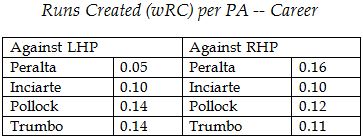

The particular beauty of this particular switch is that it doesn’t really come with an offensive cost; we’re assuming that Peralta could be forced to face a lefty if he stayed in (or, if last night’s lineup is any indication, the opposing team might then have to let Paul Goldschmidt or Mark Trumbo face a lefty). But let’s say we knew Peralta could face a RHP one more time but for the two innings of defensive replacement. Against RHP, Inciarte has created 31.8 runs (wRC) in 312 PA (0.10 wRC/PA), and Peralta 42.9 runs (wRC) in 271 PA (0.16). If you knew Peralta’s spot in the lineup would face a RHP in the later PA, you’d probably leave him in; 0.03 runs of defensive value is easily eclipsed by the 0.06 gap in runs the two players would be expected to create.

So far in his career, Peralta has created about 0.05 runs per PA against LHP, to Inciarte’s 0.10 (yeah, same as against RHP for Inciarte so far). Hence the high likelihood of replacement; if it’s a RHP you’d be up 0.06 runs with Peralta, but if it’s a LHP you’d be down 0.08. Expanding our scope:

If you consider Inciarte and Pollock to both be 20 UZR/150 type players in CF, and Trumbo a -20 UZR/150 player in right:

In the D-backs’ case, the surplus offensive value all comes by virtue of Peralta’s platoon split, and to some extent Pollock’s (0.02 RC/PA). If you assume Pollock or Inciarte would do well in right field, the biggest defensive advantage comes from replacing Trumbo; the only other meaningful difference on defense is in left field, between Inciarte and Peralta.

To manage this situation successfully requires some care; a single inning of surplus value on defense is worth half as much as two, obviously. And anyone who tried this would have a significant error rate, I would think, especially since it involves decisions that the opposing manager would make. The thing is, though, it’s not even that simple.

Reducing run value to innings for defense and PA for offense should feel unsatisfying, because it is. Runs come in increments of 1. In most PA, all four of these players are most likely to do the exact same thing: record an out. In most innings, each outfield position is most likely to field the ball zero times, and most plays will be made equally as well by any of these outfielders.

Defensive replacements aren’t about these small runs-per-something differences; they’re about the big play. If you lift Peralta, are you robbing yourself of a home run like the one he hit last night? If you don’t, are you risking a misplay in the outfield… like the one last night? If it’s just about the big play, then the choice becomes easy when the team is ahead; the importance of scoring more runs is not quite as high as the importance of preventing them from scoring. Offense is incremental, and doesn’t quite fit this way of looking at things, but defense does.

We can look at innings played leaders for left fielders as a rough guide. Alex Gordon was a 22.6 UZR/150 defender in left, pretty close to what we’re considering Inciarte to be out there. Justin Upton played the next-most innings, and was a -1.1 UZR/150 player, pretty close to how we’re viewing Peralta (convenient, right?). After adjusting for the difference in innings played, Gordon made about 58 additional defensive plays over and above those made by Upton. If we use this for a back-of-the-envelope guess and adjust for the fact that more than one of these plays could be made in any particular inning, the chances that Inciarte would make a play that Peralta wouldn’t in any one particular inning is about 1 in 27. Not all of those not-plays would cause run(s) to score, but about half of them would.

If you’re up by a couple of runs in the seventh, the choice should be pretty easy if Inciarte is available for left field (either by shifting from center or coming in as a substitution). In that situation, the chances that those two players’ difference in defense would make the difference in winning or losing is, ballpark, 1 in 100 (if we say 1 in 50 for runs scoring, but note that the other team could score runs in other ways, and note that the D-backs could also score runs). Coming up with a similar number for offense for, say, Inciarte and Trumbo would be very difficult, but I think you can still see some evidence in the numbers for changing strategies based on whether the team is ahead or behind. With respect to Peralta, however, there is no guarantee that he’d be a better bet than Inciarte offensively, at least late in games where the identity of a pitcher a couple of innings down the road is almost impossible to guess. Inciarte and Pollock can’t sub for both Trumbo and Peralta at the same time. The best course, then, is for Inciarte to spell Peralta once a RHP starter is lifted — maybe even regardless of score, and especially if it can be timed for a double switch.

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

It's a real pleasure to be a colleague of @MATrueblood's. His latest @PenningBull newsletter on the Josh Donaldson/… https://t.co/Z9x60r7Jqc, 55 mins ago

It's a real pleasure to be a colleague of @MATrueblood's. His latest @PenningBull newsletter on the Josh Donaldson/… https://t.co/Z9x60r7Jqc, 55 mins ago I once shared a dinner table with a Holocaust survivor and a Supreme Court Justice. One of those times you don't re… https://t.co/CxGOHhOtiZ, 19 hours ago

I once shared a dinner table with a Holocaust survivor and a Supreme Court Justice. One of those times you don't re… https://t.co/CxGOHhOtiZ, 19 hours ago Same https://t.co/VZn7TndXiR, 21 hours ago

Same https://t.co/VZn7TndXiR, 21 hours ago Seemed like one more veteran reliever was coming, Rondon is it. Solid righty, gets ground balls, has been a little… https://t.co/LQXSOAzopS, 21 hours ago

Seemed like one more veteran reliever was coming, Rondon is it. Solid righty, gets ground balls, has been a little… https://t.co/LQXSOAzopS, 21 hours ago RT @OutfieldGrass24: Who are some players that, last winter or spring, prepared swing changes for 2019? Anyone come to mind?, 24 hours ago

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Who are some players that, last winter or spring, prepared swing changes for 2019? Anyone come to mind?, 24 hours ago

Powered by: Web Designers