Refocusing the Race for Second Bullpen Lefty

If “spring training” means “roster battles,” then “roster battles” means “second lefty reliever competition” almost as much. You may not end up having too many conversations about it this year, but there is news, and new analysis to be done — and how things have shaped up so far sheds some light on other, bigger ticket questions this spring. Today, the D-backs reassigned Daniel Gibson and Scott Rice to minor league camp, telling us an extreme ground ball plan isn’t something the D-backs will adhere to slavishly.

First, from a preview on Leap Day on what to watch for this spring:

Second LHP in the bullpen. Remember last year, when it seemed to come down to Andrew Chafin and Dan Runzler? Stay tuned for a non-Broadway revival featuring a new cast. Matt Reynolds may be in the catbird seat, but there’s a whole host of dark horse candidates, from Keith Hessler to Daniel Gibson to Scott Rice. This is less about the outcome of the competition for me, as much as what the competition will be by mid-March. My money is on Scott Rice, who fits the ground ball plan perfectly and seems most likely to play the Runzler role.

Swing — and a miss. Fortunately I don’t know where to make obscure sports bets except on The Pool Shot, and the most I’ve ever stood to lose there was a cheeseburger. But as I said then, this was about what the competition would be by mid-March, and here we are.

Gibson was the upside play, the one who stood the best chance to make a jump up and immediate impact the way that Andrew Chafin did last year, after a 2014 cameo. Unlike Chafin, Gibson has been a reliever throughout his three year minor league career. Still, Gibson’s future may be a lot like Chafin’s, a good overall reliever who is aimed at lefties but not relegated to a matchups role. Last year, lefty hitters (mostly at High-A and Double-A) finished with a laughably low .423 OPS against Gibson, who threw as hard as 94.7 mph last fall (release speed). Righty hitters also fared very poorly against him, however: a .582 OPS. There’s a substantial platoon split there, but a ton of room between a .151/.237/.186 slash line vs. LHH and “still really good.” Maybe now’s not the time — Gibson will probably have the ignominy of the worst ERA of the spring (32.40 ERA in 1.2 innings), but the chorus will be louder a year from now, if Anthony Banda hasn’t done an even more convincing Chafin impression by then.

Rice was more of the tea leaves guy, someone I was probably especially conscious of because he was signed while I was working on a piece laying out the evidence that the D-backs have been highly committed to building a grounder-oriented organization through pitching acquisitions. Rice fits that model, with an astonishing 68.5% ground ball rate in the minors last year. But he’s not your classic case in other ways: Rice was the ripe old age of 31 when he made his debut for the Mets in 2013, a full season in which he pitched in a matchups role (73 G, 51 IP), with okay-ish results (3.71 ERA). Things didn’t go as well for Rice the next year, and while still in the Mets organization in 2015, he actually did quite well. I think there’s a problem in the data (which says he threw right-handed for 3 PA), but the rest has him holding LHH to a pedestrian .687 OPS — and RHH to a .442 OPS. Chances are he wasn’t left in to face the Las Vegas 51s’ most dangerous RHH foes, but that’s really very good.

***

With Will Locante already optioned, the left-handed bullpen candidates still in camp are down to three: Wesley Wright, Keith Hessler, and Matt Reynolds. It’s still Reynolds in the catbird seat, but it is turning into a three-way race with no one at all: Reynolds has already given up one big fly in 3 innings, and each of the other two pitchers has yet to yield a walk.

The D-backs signed Reynolds to a $675k contract to avoid an arbitration hearing, but unless the terms of the deal depart from what the default would be in this situation, the D-backs can sidestep more than $500k of that amount if they prefer not to take him with them to Chase Field when they break camp. Reynolds had a fine partial season when he debuted with the Rockies in 2010, and he pulled the same trick after getting claimed by Kevin Towers on waivers: his 1.98 ERA for the D-backs in 2013 was partly but not even mostly luck, although it came in just 27.1 innings (30 games). His return was not nearly so good last year, either in 50 IP with Reno (5.58 ERA) or in his brief MLB stint of 13.2 innings (4.61 ERA). As things stand, Reynolds has a 3.66 career ERA, but it’s backed with a very high 4.58 FIP.

It’s Wesley Wright with the longest track record: 307 career innings to Reynolds’s 167. Like Reynolds, though, Wright has been every bit a matchups lefty over that longish career, posting a 4.16 ERA in 371 games. Walks have been a problem for Wright, in echoes of Joe Thatcher: despite giving up less than one hit per inning pitched, Wright has an unsightly 1.40 WHIP due to a high 3.96 BB/9. Wright’s track record with the Astros, Rays, Cubs, Orioles, and Angels — for whom he pitched in the last three seasons — begs the age old question: how good must a matchups lefty be to be a matchups lefty? Wright hasn’t had obscene platoon splits, but it’s always hard to tell whether that’s partly the result of being steered away from particularly troublesome right-handed hitters.

Finally, there’s Hessler, he of the 8.03 ERA and 6.38 FIP in his 12.1 innings of work with the D-backs last season. Hessler gets a bad rap (and is a bad rap) for a handful of epic disasters, mostly in August of last year — when he was put into matchups duty to end the season and no longer pitched more than two thirds of an inning, he rattled off five consecutive appearances without yielding a hit, recording nearly half of his outs via the K. He has an uninspiring minor league track record, but may have gotten a bump last spring: after working with the new coaching crew a year ago, he came out firing in his second season as a reliever, tearing up High-A (no ER in 14.2 IP) and dominating in Double-A as well (0.71 ERA in 25.1 innings).

But there’s also: no one. I’ll believe the D-backs can make it through most of this season with a 12-man pitching staff when I see it, but that’s the intent right now — and it’s hard to imagine getting that done unless all seven relievers on the staff are called on for more than a batter or two at a time. There probably just isn’t a role for a lefty in a purely matchups role, and other than Andrew Chafin and someday, maybe Daniel Gibson — we haven’t talked about anyone that looks like a reliever that can average over an inning per outing. So who cares?

It’s not always the case that ERA tells the “right” story about pitchers, and it’s even more rare when it’s the right tool to use in evaluating relievers. Here, though, I think we have what we need. Where a pitcher like Wright is intended to be used in a matchups role, he is almost certain to actually face an almost equal number of RHH. That’s what Wright’s stats show, for example. No one would take the stance that a matchups lefty should be rostered in lieu of a righty that is likely to be more effective than lefties — but a righty with a regular platoon split that is only slightly worse against lefties than a matchups option should probably be considered, as well.

As things stand, the D-backs seem likely to roll with Brad Ziegler, Andrew Chafin, Tyler Clippard, Daniel Hudson, Randall Delgado and Josh Collmenter in the bullpen. If there’s only one other spot left for grabs, it’s the only spot for which Silvino Bracho is eligible — it’s also the way that Evan Marshall, Zack Godley, Jake Barrett or Enrique Burgos could get there.

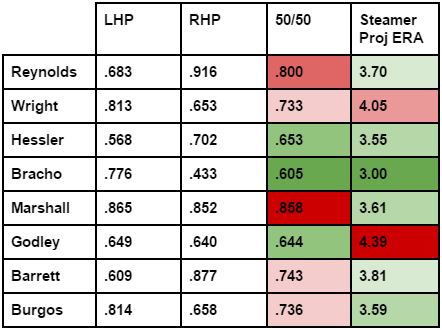

As it happens, the lefties above and the righties just mentioned as in competition for a spot all spent most of last season in the minors. Here are their minor league splits, by OPS — and those marks averaged together, as if they were going to face the same mix of batters that Wright faced last year. Also included are Steamer projections for each pitcher’s ERA.

Even Hessler, who had such success last year in the lowish minors — his results are better than, say, Barrett or Burgos in a lefty matchups role, but not to a crazy extent. And while Hessler had a 200 basis points advantage over Bracho against lefties, even mixing in a lower-than-normal percentage of righties makes that advantage evaporate.

As we’ve noted a few times here before, last year Bracho showed so elite a fly ball rate that it was a significant asset — and, amazingly, he coupled that with a strong strikeout rate. He’s the only D-backs pitcher projected by Steamer to have a lower ERA this year than Zack freaking Greinke. What’s more, although Bracho relies on a slider that might be expected to have a large platoon split, his fastball happens to have almost purely vertical movement — the kind that tends to have the smallest platoon split. As noted back in December:

My interest in Bracho (today — the guy’s interesting) was why it seemed like he had a small platoon split in the minors. Could he act like an intermediate lefty, I wondered, or at least be a decent option among RHP in the bullpen? Well, in the majors, Bracho’s four-seam had an average 10.5 inches of vertical movement, with just -1.9 inches of horizontal movement. We’d expect a fastball/slider guy to be very vulnerable against LHH â and the slider is still a liability there â but thereâs reason to think Bracho won’t ever be that vulnerable against LHH.

And as Jeff recently explored, Bracho may have managed this unusual batted ball profile (and the platoon splits) with an extreme drop-and-drive delivery that, from as short a pitcher as Bracho, deletes the downward plane that most pitchers manage — compared with other pitchers that a batter probably faced that day, it probably does look like Bracho’s fastballs are moving up. Seems like a pretty easy decision, no?

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04 RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

ICYMI, I posted my #DbacksMinors top-10 prospects yesterday. You can find those rankings and the entire top-30 here: https://t.co/zOJeYnBrnk, 10 mins ago

ICYMI, I posted my #DbacksMinors top-10 prospects yesterday. You can find those rankings and the entire top-30 here: https://t.co/zOJeYnBrnk, 10 mins ago RT @CLEFOAINTACRIME: Here's my Goldy trade magnum opus/agitprop https://t.co/Ba2sVmOBnn, 1 hour ago

RT @CLEFOAINTACRIME: Here's my Goldy trade magnum opus/agitprop https://t.co/Ba2sVmOBnn, 1 hour ago RT @TheAthleticAZ: Today, our Live Q&A on @Dbacks at noon.

Goldschmidt's gone, and @ZHBuchanan takes subscribers' questions. from noon… https://t.co/sOamb1msqd, 2 hours ago

RT @TheAthleticAZ: Today, our Live Q&A on @Dbacks at noon.

Goldschmidt's gone, and @ZHBuchanan takes subscribers' questions. from noon… https://t.co/sOamb1msqd, 2 hours ago RT @enosarris: Let’s debunk some myths surrounding Patrick Corbin https://t.co/lzhOTIAmyt, 23 hours ago

RT @enosarris: Let’s debunk some myths surrounding Patrick Corbin https://t.co/lzhOTIAmyt, 23 hours ago RT @TheAthleticAZ: Here's an emerging metric that brings some #Dbacks optimism. @OutfieldGrass24

https://t.co/eKQBpe0H7M, Dec 05

RT @TheAthleticAZ: Here's an emerging metric that brings some #Dbacks optimism. @OutfieldGrass24

https://t.co/eKQBpe0H7M, Dec 05

Powered by: Web DesignersResources

FanGraphs Stats Glossary

Nick Piecoro Author Page

Cot's Baseball Contracts

BP Base Running Stats

Previously on The Pool Shot, the guys explained some of their favorite advanced stats. Hitting, including wRC+, HHAV and batted ball; pitching (38:00), including FIP, xFIP and SIERA; and baserunning and defense, including UBR, UZR and DRS (58:00).