Why the 2015 Sinker Experiments Didn’t Work: Understanding Platoon Splits of More Kinds of Fastballs

Its not that often that I feel like the scales have fallen from my baseball eyes, but it just happened, and I’m excited to share why. It’s not that this one thing Explains All Baseball, but the effect seems to be enormous: whether or not a pitch has a platoon split has much to do with how vertical the movement is. Seems simple, right? And intuitive; we’ve seen cutters and curveballs do well when a pitcher faces a hitter of the opposite hand. But some changeups seem to be big weapons in those circumstances, and some not. And the real trail leads through fastballs.

To explain what I mean, we need to talk about fastballs a bit first. In these parts, we tend to use the pitch classifications used by Pitch Info at Brooks Baseball (which are very, very good). Cutters are cutters, and four-seam fastballs seem pretty consistent. In common parlance, though, “sinker” and “two-seam fastball” are frequently treated like they are one pitch. They’re probably not. But there’s also a broad range of four-seam fastballs.

To talk about something in the aggregate, we need categories. The fact that we can see categories is part of what makes the human brain so effective. We rely on that ability in order to function in day to day life and in making decisions of all kinds. But knowing that we have a predisposition toward categorizing means knowing the dangers, too. “Salty is an offensive catcher” can mean you’ve written off his defense, and that you become less sensitive to just how bad or not-bad that defense is. It’s hard to make decisions through a fog of shades of gray.

Back in 2010, Max Marchi — more recently, of the Cleveland Indians — took a crack at putting pitches into more categories with more gray. In talking about different kinds of curveballs, Marchi observed:

I’m fine with classifying them both as curveballs when writing a top 10 list, like “here are the 10 best curveballs in MLB ranked by Run Value.” On the contrary, I’m not so comfortable when evaluating batters’ abilities against certain type of pitches. For example, when facing right-handed pitchers, Mark Reynolds seems to have success against hard curves (+0.87 runs per 100 pitches in 2009), but suffers against uncle-charlies (-0.26). On the other hand, Pablo Sandoval holds his own facing slow curves (+0.24), while being helpless against tight ones (-0.76). I don’t care whether Burnett and Carpenter call their pitch simply curveball: Hitters are definitely seeing two different animals and reacting to them in different ways with different degrees of success.

When we’re talking about the very center of the game, the pitcher versus hitter showdown, we’d care if one pitcher’s two-seam fastball was more similar to four-seam fastballs. We’d care, because the hitter would. They’re not guessing up there (at least, not all the time) — they’re adjusting. Doesn’t it make a ton of sense that hitters would have tendencies with those adjustments? That some might adjust better to changes in speed, that some are especially bad at lengthening or shortening their arms mid-swing, that some are more skilled at changing their swing plane?

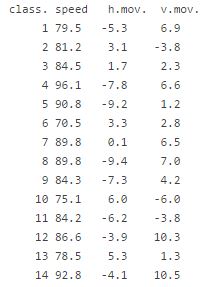

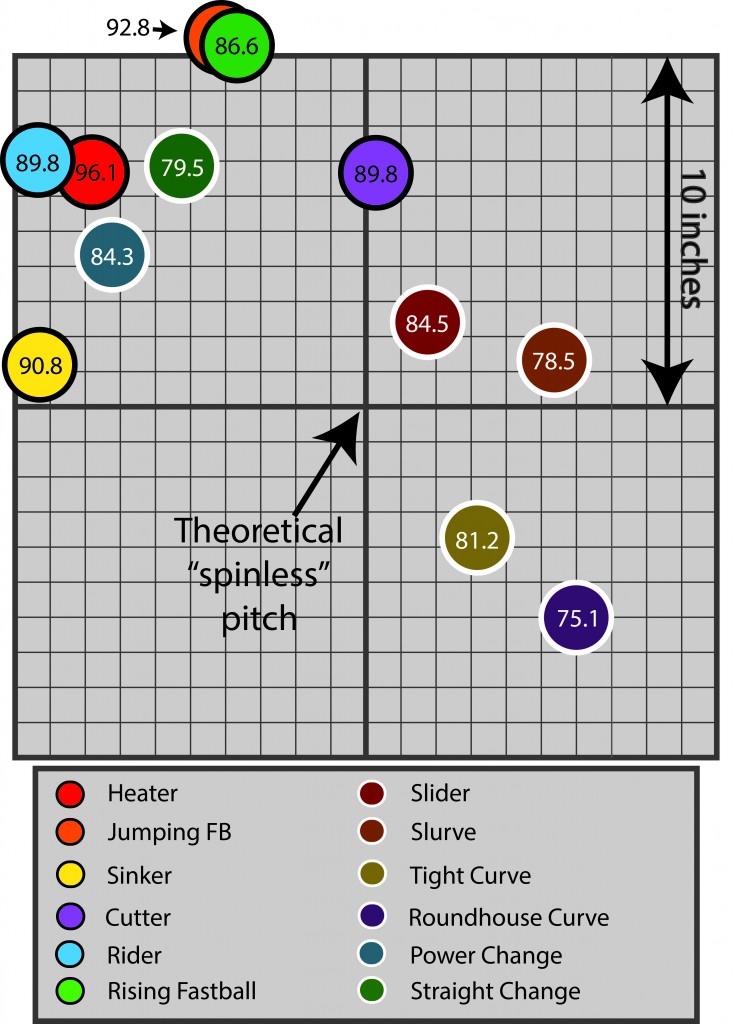

Marchi set out to let the PITCHf/x data more or less categorize itself with a cluster analysis. As he disclosed, the only way to get a result was to make some choices of his own, too, but for where we’re going in a minute (platoon splits), we don’t need Marchi to have made the perfect decisions. We just need more data. And using speed, horizontal movement, vertical movement, and release point as classifying variables, Marchi came up with 14 separate classifications. As he explored — they weren’t too easy to name. And names aren’t necessarily that helpful, either. From that Marchi article, the average characteristics of pitches in each of his 14 clusters (these and later numbers are only for right-handed pitchers):

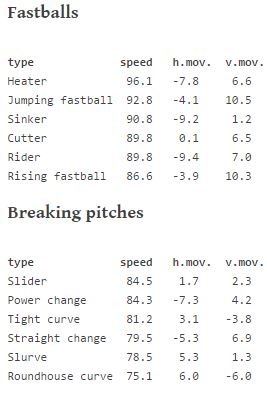

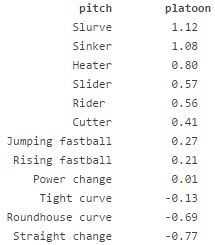

Okay, maybe we need names after all. Marchi followed up a couple of weeks later with an article that is the real reason for bringing any of this up: one providing platoon splits for this enhanced number of pitch categories. And for that analysis, he didn’t get into platoon splits for “floaters” or “submariners,” which are categories 6 and 11 above, respectively. That left the other 12:

Let’s get one thing straight: not all pitches fall neatly into these categories. But at the point of this analysis, Marchi was using three entire years’ worth of PITCHf/x data, something like over two million pitches. Yes, fastballs are cut up into smaller pieces. But we’re still talking about the ultimate sample size here. The least common pitches — the floaters and submariners — are left out. Given the size of the data set, if there are strong tendencies among these pitches, we should trust them.

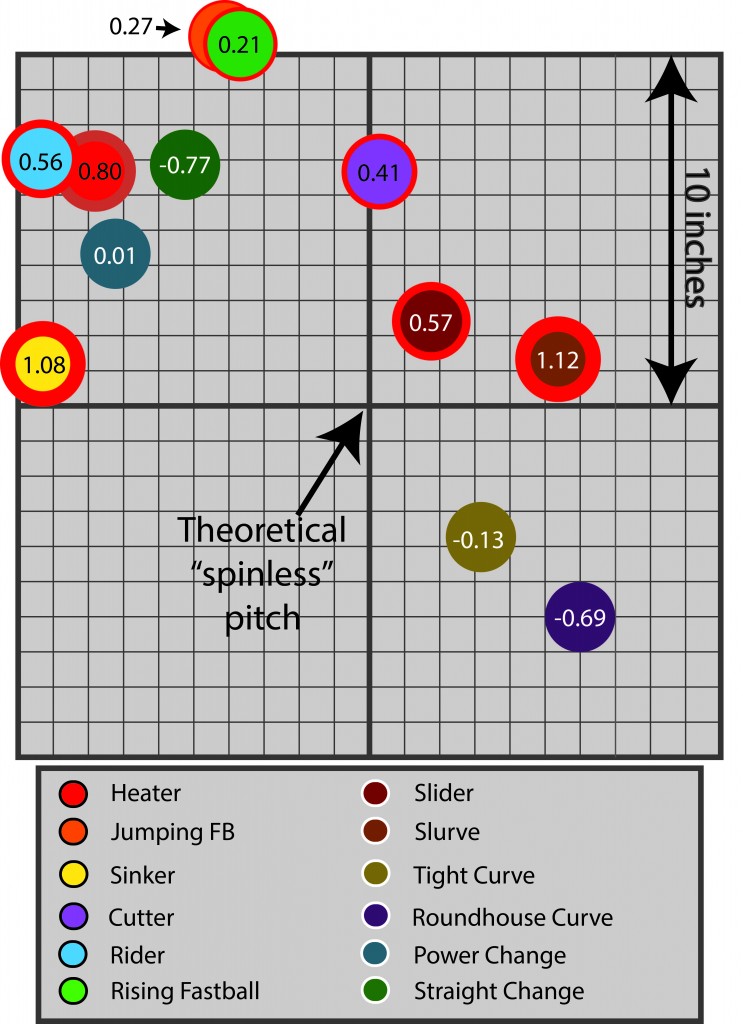

As it turns out — with respect to platoon splits, the differences among these pitches are ENORMOUS. Marchi used multilevel modeling to remove the effect of ball-strike counts on the results, and to neutralize the effect of pitcher quality. We’re just talking about the pitches themselves. He published his results in terms of Run Value per 100 pitches thrown:

Consider this: Chase Anderson has one of the least balanced repertoires among D-backs pitchers, with an excellent changeup and poor fastball results. His change has a Run Value per 100 of 1.32, and his fastballs -0.53. The difference between the platoon splits of Marchi’s two curveballs is greater than the difference between Anderson’s fastballs and league average fastballs. The difference in slurve effectiveness between throwing it with the platoon advantage or not is about as big as the difference between Zack Greinke‘s 1.20 Run Value per 100 fastballs and league average fastballs. This is huge, friends. Huge.

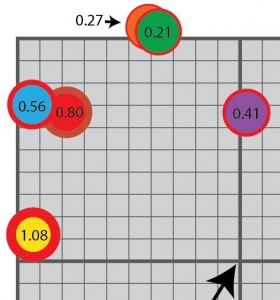

The scales-from-eyes moment happened for me when looking at these 12 pitch classifications on a plot (and diving into the platoon splits of D-backs pitchers’ pitches, with plots of their movement — back to that in a second).

Compare the same thing with just Marchi’s Run Value per 100 pitches numbers for platoon splits:

Velocity clearly matters here; the straight change and roundhouse curve have strong reverse splits, and the main difference between a rider and a heater is velocity. But I’m not wrong, right? Doesn’t the vertical/horizontal movement thing really stand out?

Consider this: no MLB player sees a “spinless” pitch… that’s why it’s theoretical. The average pitch a player sees is weighted toward fastballs, maybe 4 inches of vertical movement and -3 inches of horizontal movement. Something like that. Through that lens, the cutter does have some horizontal movement — in the opposite direction. The jumping fastball and rising fastball have almost perfect vertical movement.

Most importantly, the sinker and slurve are the big time platoon pitches, and whether you look at it as a comparison to 0,0 on this plot or to the average pitch, their movement is almost perfectly horizontal… just to different sides of the plate. The slider fares better without much more vertical movement, but it has less horizontal movement. Ask Justin Masterson how fun it is to face lefties with just a true sinker and a slurvy slider.

A lot of this confirms things that I think we already felt like we knew. When a right-handed pitcher faces a left-handed batter, curveballs and changeups are that pitcher’s friend; sliders are not. I think it’s great, useful information, though, to know that slower changeups with more vertical movement are more effective when a RHP faces a LHH. And then there’s fastballs.

Every pitcher throws some combination of fastballs most of the time; fastballs are the name of the game. If your fastball matched up poorly with the hitter you were facing, you’d be in some trouble. Look at the array of fastballs here.

Remember, we’re dealing with the mother of all sample sizes, about 2 million pitches — most of them fastballs. And a difference of 0.8 Run Value per 100 pitches is enough to take you from “this is pretty bad” to “hey, this is pretty good.”

Remember, we’re dealing with the mother of all sample sizes, about 2 million pitches — most of them fastballs. And a difference of 0.8 Run Value per 100 pitches is enough to take you from “this is pretty bad” to “hey, this is pretty good.”

Isn’t this clear as day? Not all pitches we see classified as fastballs or four-seamers or two-seamers or sinkers are made alike. Few pitchers use fastballs that fall neatly into one of these six categories. But it does look like there’s a general principle here: more vertical movement is good, more horizontal movement is bad. And, for good measure: if you’re going to throw really hard, maybe don’t emphasize that one as much.

This principle has a ton of practical applications for what happened with the D-backs’ sinker experiments this year. In a follow-up, I’ll tease out some of the more interesting things I find. But these are a few of the things I’m talking about:

1. Chase Anderson’s four-seam fastballs look like jumping fastballs, his sinker has the movement of a rider — and the velocity makes it more like a heater than a rider. Heaters are bad ideas in platoon situations. Yet, even though this data would tell us that his four-seam would be an asset against LHH and his sinker would absolutely not be, he did the opposite in 2015; he threw the “sinker” just 17.7% of the time against RHH, but 29.0% of the time to LHH. Lefties had an average of .231 or lower against all of Anderson’s other pitches, but lefties tuned up the sinker: .424 average, .697 SLG. BAD IDEA. NO MORE SINKERS AGAINST LEFTIES. The four-seam should work.

2. Rubby De La Rosa‘s repertoire is laughably close to a worst-case platoon scenario. His fastball is a heater, except harder. His slider hurts, and doesn’t help. His two-seam is one of the only D-backs pitches that actually look like one of the yellow “sinkers” above — also bad news. Sure, there’s the change, but it’s a power change. Jeff wrote earlier in the season that RDLR had moved toward sinkers in facing lefties. Toward the end of the season, it was pretty clear that that did not work, at all. It also looked (in that same last piece) like RDLR’s sinker was very helpful in facing RHH — that, too, looks like it’s supported by the data above (against RHH, a RHP wants the numbers above to be as positive as possible).

3. I ended up with the topic of this piece when loose Anderson ends I was working on came together with some Collmenter ones… and some Bracho ones. My interest in Bracho (today… the guy’s interesting) was why it seemed like he had a small platoon split in the minors. Could he act like an intermediate lefty, I wondered, or at least be a decent option among RHP in the bullpen? Well, in the majors, Bracho’s four-seam had an average 10.5 inches of vertical movement, with just -1.9 inches of horizontal movement. We’d expect a fastball/slider guy to be very vulnerable against LHH — and the slider is still a liability there — but there’s reason to think Bracho won’t ever be that vulnerable against LHH.

So much more. Forget Brad Ziegler — that guy’s out. But Josh Collmenter makes so much sense here; his curveball was supposed to help, but it backfired, for reasons we can explain. I think we might also finally unravel the enigma of Randall Delgado, and explain a lot of Robbie Ray‘s success. This is going to be fun, friends.

11 Responses to Why the 2015 Sinker Experiments Didn’t Work: Understanding Platoon Splits of More Kinds of Fastballs

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

RT @ZHBuchanan: If you haven't filled out our Diamondbacks fan survey yet, there's still time. We want to hear from you!

https://t.co/ctzkNTbk5s, Jan 13

RT @ZHBuchanan: If you haven't filled out our Diamondbacks fan survey yet, there's still time. We want to hear from you!

https://t.co/ctzkNTbk5s, Jan 13 “Top US News: Tesla merch now available for purchase with Dogecoin”

The point at which I wish to formally withdraw… https://t.co/7k38A7nDCQ, Jan 14

“Top US News: Tesla merch now available for purchase with Dogecoin”

The point at which I wish to formally withdraw… https://t.co/7k38A7nDCQ, Jan 14 Ya boi with the feature image https://t.co/g3SMJYmAQq, Jan 14

Ya boi with the feature image https://t.co/g3SMJYmAQq, Jan 14 Nelson fell asleep waiting for Simcoe to get home from the groomer. I’m jealous, honestly. https://t.co/CO4FZtwhUJ, Jan 13

Nelson fell asleep waiting for Simcoe to get home from the groomer. I’m jealous, honestly. https://t.co/CO4FZtwhUJ, Jan 13 RT @OutfieldGrass24: Dynasty question: Daniel Espino, Emerson Hancock, and Quinn Priester. Gotta cut one. Who should it be?, Jan 13

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Dynasty question: Daniel Espino, Emerson Hancock, and Quinn Priester. Gotta cut one. Who should it be?, Jan 13

Powered by: Web Designers

Fascinating stuff. Great work!

La Russa and Duncan were looking to repeat the success they had with Kyle Lohse when they talked him into throwing mostly 2 seam fastballs, which turned him into a stud pitcher…

I’m with you there. In Lohse’s best season, 2012, he did throw sinkers to lefties for almost half his pitches against them. With great success; they hit .219 off of the pitch.

The difference: Lohse’s sinker had an average of 8.7 inches of vertical movement. That’s more than many pitchers’ 4 seamers. I think that helps confirm the theory, not undermine it. Not all sinkers are alike, and their vertical movement helps explain why some have terrible platoon splits and some not.

[…] that this was not necessarily Marshall’s idea. What’s more, as we explored recently, when RHPs throw sinkers to lefty hitters, the results can be really bad. Count Marshall among those pitchers; 61.25% of his pitches to lefties in 2015 were sinkers, and […]

[…] to more sinkers from Diamondbacks pitchers, but as Ryan proved to us in the waning moments of 2015, sinkers aren’t for everybody. As he showed, thanks in large part to the strong research by Max Marchi, vertical fastball […]

[…] are reasons — the changeup isn’t going anywhere, and even before last season began, we probably should have realized that throwing a ton more sinkers to lefties would be a bad idea. That last was so significant a […]

[…] for RHH. Take a look at the movement chart above from Brooks Baseball. Remember when we found that the more horizontal a pitcher’s pitches were in movement, the bigger his platoon split? Clippard has tremendous vertical movement on his fastballs, over 10 inches on both of them in all […]

[…] long ago, we worked through some research that betrayed a general principle: the more horizontal the movement on a pitch, the more susceptible to large platoon splits it was l…. The converse — that when the movement of a pitch was more or mostly horizontal, the bigger […]

[…] more, we did some work over the offseason on platoon splits for different kinds of pitches, thanks to some excellent work by Max Marchi some years back at The Hardball Times. Marchi only […]

[…] are probably not the same as righties, but while we have an exhaustive study about all kinds of pitches and their platoon splits for righties… I’m just not aware of a similar study for lefties, and I’m not capable of that […]

[…] against righties, we know from the Max Marchi platoon split numbers (find a full explanation here) that some types of pitches have dramatically different platoon splits, and some large trends jump […]