Robbie Ray Breaking Balls

Has Robbie Ray been unlucky this season? He sports a weirdly high .343 BABIP this season, and a staggering 27.0% line drive percentage — both numbers that few pitchers maintain over the course of a season. Last year, the highest BABIP for a qualified starter was Gio Gonzalez‘s .341 — and even after getting shelled last night, Gonzalez has made that figure look fluky by pulling in with a 2.87 ERA (and .277 BABIP) this season. The highest line drive percentage by a qualified starter last year was Jason Hammel‘s 24.5%, and he, too, has made that look fluky by registering a 2.31 ERA (and 20.2% LD%) through 8 starts. As Jeff has explored, line drive percentage is very unstable year to year.

Things have changed for Ray this season, though. Last season, the story was about foul balls; Ray got to 2-strike counts with relative ease, but struggled to put the finishing touches on plate appearances. In a slow-pitch softball league where a second foul with 2 strikes is a strikeout, Ray would have been dominant. In 2015, Ray was a little more “annoying as all hell” to batters.

In the early going, it looked a whole lot like Ray was dealing with foul ball woes very well:

What’s really interesting: that foul% in 2 strike counts so far this year is substantially improved: just 26.7% of pitches overall, and 44.4% of swings. Compare that with the real problem last year: Ray threw 690 2-strike pitches in 2015, an incredible 211 of which were fouled off. That’s 30.6% of pitches overall, and a crazy 50.5% of swings. You didn’t imagine it: batters just wouldn’t die last year when Ray had them on the ropes. Things aren’t necessarily a whole lot better, but they at least look better.

And the bottom line: he has been more efficient. So far in 2016, Ray has thrown 15.9 pitches per inning, just a hair above average, but a monstrous improvement from his 17.7 pitches per inning rate in 2015. He’s accomplished that in an unconventional way.

That way? A microscopic Zone %, meaning Ray was pitching out of the strike zone far more often. But things didn’t stay the way they were in spring training, and in Ray’s first start of the season. At this point, Ray has moved backward, not forward. His pitches per inning is now a staggering 18.9 — a lot like saying that, on average, Ray has thrown 94 or 95 pitches just to get through 5 innings. Not good.

Last year, Ray threw 39.2% of pitches in the strike zone; since that April piece was written after his first season start, he’s thrown 41.8% of pitches in the zone. That ease with which he got hitters to two strikes last year? In 2015, 60.7% of first pitches of an at bat went for strikes (or hits, etc.). This year, that’s been flushed like so many dead goldfish: a 51.6% rate. Last year, he had a first pitch strike rate almost exactly the same as league average; this isn’t just low now, it’s way low.

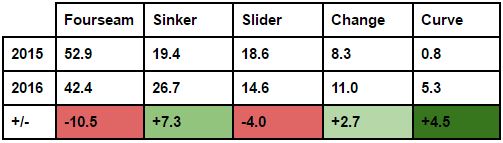

I know what you’re thinking. Repertoire change, right? Right.

In truth, the drop in fourseam usage is not as dramatic as it looks; at the beginning of Ray’s time in the majors last season, Ray was pumping fourseam fastballs around 60% of the time, slowly tailing into the mid-40s as the season wound down. The same goes for the sinker; by September of last year, Ray was using the sinker about as often.

What with throwing just three changeups last September (and what with all three of them being hit for home runs), the changeup usage is a lot more surprising, even though the difference is slight. And, most of all: Ray’s curve doesn’t look like the occasional hanging, misclassified slider. It looks like he’s using it on purpose. I know. I’m scared, too. Ray has been a fastball artist in search of a third pitch he could lean on. Could it really be the case that now, he has three third pitches?

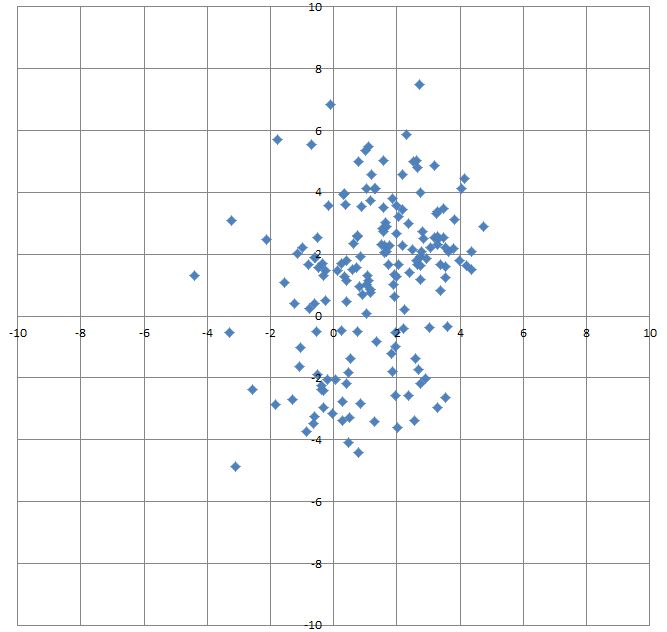

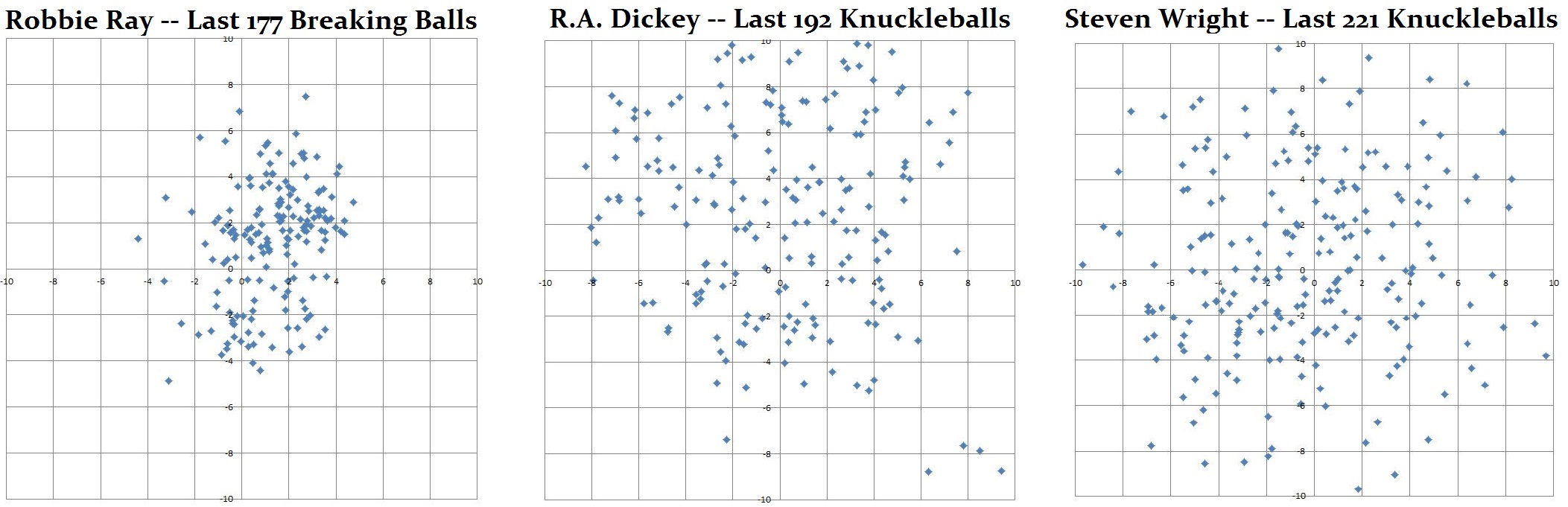

We’ve been over this before, a few times. In spring training last year, it looked like Ray had cracked the code, and his breaking ball was much more consistent. By the end of the 2015 season, it seemed appropriate to dub Ray’s breakers “The Slurge.” Color me not convinced we’re around the bend(er), and seeing distinct breaking pitches. No, it’s not like any pitchers’ pitches will look perfectly distinct when you plot them all out separately. But can you tell where the sliders end and the curveballs pick up on this pitch movement plot?

I don’t look at pitch plots like this every day, but I’ve done more than a few. The thing this reminds me of most is a knuckleball (here’s an example). A ball that comes in at 0,0 on a pitch plot like this has moved as if it had no spin at all — but that’s kind of impossible, because baseballs have seams, and if you actually threw it with no spin, it would flutter around. With a knuckleball, I’d conclude that pitches around 0,0 moved one way — and then moved back.

With these? I have no idea. I’ve found it helpful to think of the true “center” of a pitch plot to be up a couple inches, and a couple inches toward the pitcher’s arm side (this was catcher’s perspective, so something like 2, 2 from a lefty like Ray). That’s the kind of movement you or I might get playing catch in earnest, although gravity would hide it. In this case, though, all that does is make Ray’s breaking balls look even more haphazard.

Could that be… a good thing? When Ray sported a tighter breaking ball in 2015 spring training, they flirted with the zero baseline in terms of up and down, but they were all to the right of the center line above — most had between -3 and -2 inches of horizontal movement. This year, not so much. And maybe that’s been helpful, a lot like a knuckleball.

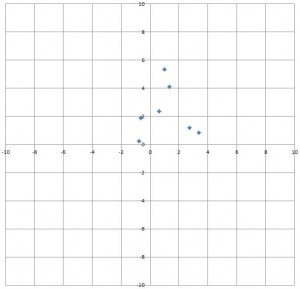

The times that Ray’s breaking balls have been hit this season, they’ve looked like cement mixers — they didn’t do a whole lot, but they tended to be up and to his arm side a bit. This plot is small, because you get the point. But, guys: Ray has thrown 177 breaking balls in regular season games this year, and only 7 of them have been turned into hits.

The times that Ray’s breaking balls have been hit this season, they’ve looked like cement mixers — they didn’t do a whole lot, but they tended to be up and to his arm side a bit. This plot is small, because you get the point. But, guys: Ray has thrown 177 breaking balls in regular season games this year, and only 7 of them have been turned into hits.

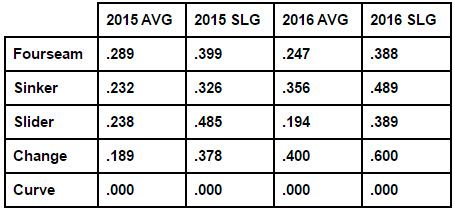

Knuckleballs are hard to hit; that’s the point. When they do get hit, though, they tend to get hit. The legend goes that against a knuckleballer, you might as well swing hard and hope for the best, because last-fraction-of-a-second adjustments are hard to make. Ray’s breaking balls have been hit fairly hard; two of those seven hits were home runs, and there’s a double in there. Hitters’ Isolated Power (SLG minus AVG) on the versions of this pitch classified as a “slider” at Brooks Baseball is a fairly high .194. But the slugging percentage is still just .389, because… hitters have just not hit it at all.

Take the curveball numbers with a grain of salt — for these numbers from Brooks, Ray threw just 17 of them last year. But the 2016 numbers may be more meaningful; that represents 47 pitches, so it has started to become remarkable that he’s yet to yield a hit with it. Still, the slider, too, has performed both very well and quite a bit better than last season. Ray’s breaking balls haven’t just been usable — they’ve been very helpful. They’ve been really good.

We saw that Ray has veered away from his fourseam a bit this season, increasing his sinker usage. It looks like hitters have made that adjustment. And while Ray’s changeup results look mediocre, we’re only talking about 8 hits on 98 pitches, 20 of which were put in play. Given that Ray was kind of forced to stop using the change by the end of last season, it’s curious that he’s increased his usage so far this year. It’s not a very good pitch, and if hitters are going to be caught guessing at the movement of Ray’s breaking balls, it might be time to move in that direction instead, as Patrick Corbin has of late.

We’ve got a lot of tools at our disposal when it comes to pitching, but one of the things we don’t have a strong handle on is this variance from pitch to pitch with the same offering. The “variance” of a knuckleball seems connected to its success; it shouldn’t tend to break in one particular direction, and if it dances enough to create foul balls and swinging strikes, it can be successful. We have no numbers for that, though. At this point, you just look at a cloud of pitches on a pitch plot, and imagine how hard it would be to barrel that pitch. Oh, and at Hunter Pence. Here’s Pence taking one of Ray’s curviest breaking balls this season on April 19th — followed by an 0-2 slider-ish version that was turned into an easy 6-3 out.

I’m starting to think that Ray’s breaking balls are successful in the ways that a knuckleball can be successful. They are nowhere near as all over the place as real knuckleballs, mind you — see below. It’s just that maybe they’ve been successful for similar reasons. As always, we’ll keep watching this. But maybe it’s not necessary for Ray to be consistent with his breaking ball. Maybe it’s tight enough to locate, but just wild enough to be successful.

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Is it possible for a baseball trade to be cursed? If so, we've found the most obvious candidate. My latest for… https://t.co/vo1fbLHN4D, 53 mins ago

Is it possible for a baseball trade to be cursed? If so, we've found the most obvious candidate. My latest for… https://t.co/vo1fbLHN4D, 53 mins ago RT @cdgoldstein: 20 minutes til chat! get your questions in!

https://t.co/6eeQBp7fxu, 1 hour ago

RT @cdgoldstein: 20 minutes til chat! get your questions in!

https://t.co/6eeQBp7fxu, 1 hour ago RT @baseballpro: Texas' trade for Corey Kluber has not gone well: He made one start before being shut down. Cleveland's return, Emma… https://t.co/0sPKyMtHQc, 2 hours ago

RT @baseballpro: Texas' trade for Corey Kluber has not gone well: He made one start before being shut down. Cleveland's return, Emma… https://t.co/0sPKyMtHQc, 2 hours ago RT @cdgoldstein: .@OutfieldGrass24 wrote about the Kluber trade and how it is extremely cursed:

https://t.co/jz7LjyM4Lq, 3 hours ago

RT @cdgoldstein: .@OutfieldGrass24 wrote about the Kluber trade and how it is extremely cursed:

https://t.co/jz7LjyM4Lq, 3 hours ago Not too far from my town, sadly https://t.co/DIKRB4ppc0, 19 hours ago

Not too far from my town, sadly https://t.co/DIKRB4ppc0, 19 hours ago

Powered by: Web Designers