Finding Another Brad Ziegler

In a land where few pitchers succeed, the consistent dominance of Brad Ziegler is positively tantalizing. Since Ziegler’s first full season with the D-backs, Ziegler has managed a 2.52 ERA, 20th among the 160 relievers with at least 150 innings in that span, and second to just Josh Collmenter on the team. But ERA is ill-equipped to measure the value of relievers. Per RE24, a counting stat that compares run expectancy from when a reliever comes in a game to how he leaves it, Ziegler vaults to 7th among those 160 relievers. Over four and a half seasons, RE24 tells us, he’s yielded 60.4 runs fewer than the average reliever.

Ziegler isn’t just good — he’s good in a way that seems to survive Chase Field’s hit- and homer-inducing environment. And that’s not an easy feat.

Ballparks are different across the sport, and they do have important nuances. It’s usually a game of tradeoffs. Baseball’s most double-friendly park over the last few years is Fenway, which yields them at a 30% higher than average clip; but there’s a tradeoff. Fenway’s homer factor has been solidly negative, making it 15% lower than the average park in terms of homer rate, according to ESPN’s Park Factors. Dodger Stadium also boosts doubles slightly (2%) while boosting homers (6%), yet discourages the number of hits overall (-6%). You can pick up a few extra hits in Miller Park (2%) while it rains home runs (28%), but the stadium’s dimensions don’t help with doubles (-1%).

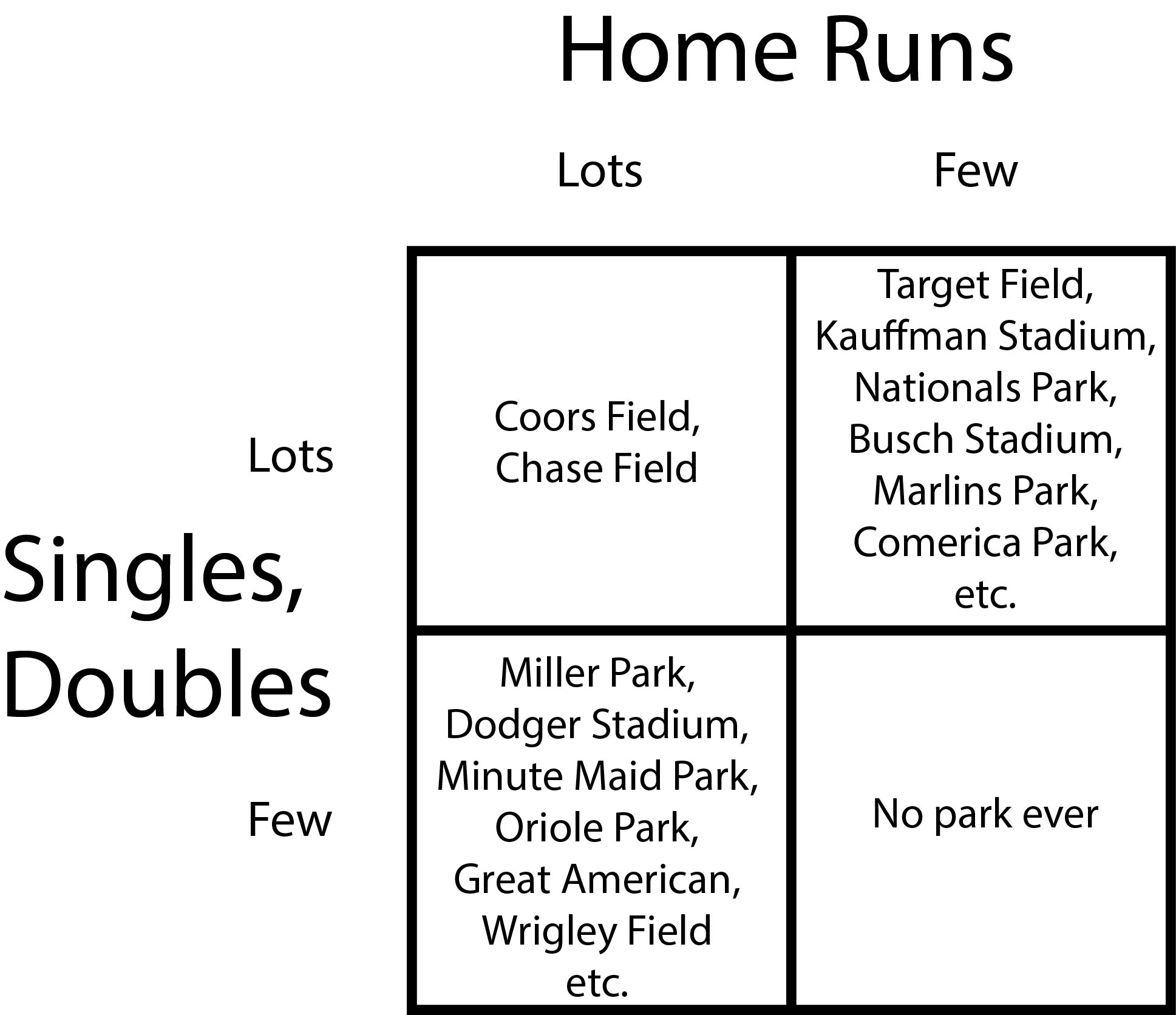

We looked on Tuesday at how much bigger the outfields of the NL West were in comparison to the rest of baseball, but noted last week in reference to the Rockies how the division had the top two hitting environments and the two worst. In Colorado, there’s fairly dry air and extreme altitude to contend with. In Arizona, there’s fairly high altitude and extremely dry air to contend with. As a result, the two parks don’t really fit on this one continuum of hit-friendly versus homer-friendly. It’s a little more like this:

Some teams may have crappy shortstops or infield defense in general, and can be predicted as a soft target for a ground ball hitter. That’s a thing you can know in advance — but it’s not an aspect of the park. This is not about infields. Instead, it’s about outfields — whether fielders have extra ground they can’t cover as thoroughly (outfield singles, doubles, triples), or whether it’s easier for a hitter to get it up and over the outfield (home runs). You could delete every team’s roster and hold a new draft, and some things would still be true about playing in different ballparks.

“No park ever” might have been hyperbole — PetCo Park comes damned close to that box if they’re not in it, and SafeCo Field has not been far behind. Generally speaking, though, if this were a graph, there are no parks all the way in the bottom right corner. To get there, you might need to dig a hole so large that air pressure is actually higher down there. If this were just about singles, maybe you could build a park in that corner that just had tremendously high walls, but still below-average amounts of real estate; we know from Fenway that we’d be boosting doubles, however. The fact that there are a couple of fields solidly in the top left box is outright strange — physics shouldn’t allow them, but the laws of baseball physics get suspended there. To be fair, Chase Field isn’t a huge boon to home runs, and it’s pretty close to that line. It’s still solidly on the left of it, though, and that’s still super weird.

You can see, then, how Brad Ziegler offers some magic. His particular brand of pitching is nearly immune to the things that makes ballparks, including Chase Field, different from others. The size of one’s outfield can dictate hit and homer rates, but what if hitters never hit it to the outfield? I understood the value of Ziegler’s ground balls in terms of how they were turned into outs so easily — Ziegler grounders have a lower batting average because more of them are hit more steeply into the ground. The value of avoiding home runs is self-evident, as well. But I have a better appreciation now of how an expansive outfield like that of Chase can really boost other kinds of hits.

The D-backs’ ground ball experiments last year didn’t seem to work, but there’s a big difference between “more than average” hits to the infield, and “Pre-death to Flying Things” Ziegler. If you’re a finesse pitcher with high contact rates, you might have a high ground ball rate, but still get as many or more liners and fly balls as the average pitcher. That doesn’t appear to work at Chase, in particular. If you can combine a high ground ball rate with a high strikeout rate, however, you’re back onto something: you’re Evan Marshall in 2014, or Andrew Chafin in 2015.

Considering this is Ziegler’s second free agent year (he signed his current extension before the 2014 season, as a fourth-year arbitration player), the man is not young — he could end up filing for free agency this October at the age of 37. Regardless of whether the team brings Ziegler back with an extension or free agent deal (more on that in the Midseason Plan), he may not last forever. The D-backs could look very naked without him. Or they could look like a team that bounces around from relying on Heath Bell to grasping at Addison Reed.

One thing the D-backs can do: make their own Zieglers. Franchise godfather Buck Showalter has been a fan of that idea:

One way in which Showalter used the whole buffalo in Arizona and later with Texas and Baltimore: encouraging some pitchers to throw sidearm. He liked having one or two of those guys around, even if they weren’t Dan Plesac. He wasn’t constantly trying to make more Plesacs; instead, when it looked like a previously-promising pitcher was about to wash out of the organization, he’d set it up so that the pitcher could get one more shot throwing with a different arm angle if they were game for the challenge (and wouldn’t you only want to do this with guys who had chosen to try it?).

The point is not that Showalter changed the course of history with this move; it’s that it had almost no downside, and it did have upside.

One could also trade for a reliever with lots of major league success, a younger version of a ground ball pitcher that has proven he’s not a fluke. There’s a guy like that out there, and he’s freakishly good in a freakish way, and for the D-backs, he offers the chance to get a pitcher who actually remains as good as advertised once he dons Sedona Red. The trouble: there’s really only one of those guys, and the Orioles really like having Zach Britton, from what I can gather. Nuts.

Trying to make a Ziegler out of a in-danger-of-washing-out minor leaguer remains a worthy endeavor, but what about trying to find a pitcher who hasn’t been great for his major league club, but could still be a pretty good fit for Chase Field? One option: a non-control artist, like the incomparable Kyle Barraclough. Another option: a guy with Ziegler-like downward movement on fastballs. Submariners and sidearmers are welcome to apply, but it’s not all about that — it’s about what the hitter actually has to contend with as the pitch makes its way to the plate.

What we’re looking for is downward break. Keep in mind, your garden variety “sinker” still rises from break — it just rises four or five inches less than the same pitcher’s fourseam fastball, and has the appearance of a tumbling pitch because gravity does a lot of work. Some of the “true sinker” pitches we’ve seen out of guys like Justin Masterson just manage to get to zero, one or two inches of rise on their pitch. Per the PITCHf/x leaderboards at Baseball Prospectus, the smallest vertical break on a sinker (minimum 50 pitches) this year is Charlie Morton‘s 1.89 (positive) inches.

We want negative inches, though. I pulled about a week’s worth of all varieties of fastballs from Baseball Savant, and got to looking. The good news: there are a few guys who do feature some negative break on fastballs at least some of the time. The bad news: not so many. Among righties, Andrew Bailey, Cory Gearrin, Hector Neris (splitters), Hisashi Iwakuma, John Lackey, Mike Pelfrey, Rob Scahill and Steve Cishek threw sub-zero fastballs at least a chunk of the time, and could conceivably throw them more often than that. The few that threw sub-zero fastballs habitually: Andrew Triggs, Peter Moylan, and arguably, Zach Neal. Among lefties, there was just one Ziegler prospect: Alex Claudio.

The Royals have the largest outfield in baseball, and have been pretty smart about taking advantage of that; chances are they know what they have in Moylan, although he still might not be worth as much to them (limiting hits) as he might be the the D-backs (limiting hits and homers). It sure seems like Triggs and Neal can’t really be worth as much to Oakland as they may be to Arizona, though, nor is Claudio a great fit for Texas or an important part of their bullpen.

Of the 170 sinker/two-seamers that Triggs has thrown this season, 92 have negative movement, and 54 of the other 78 had between zero and 2 inches of vertical break. 33 of the pitches broke downward by two inches or more; he’s thrown a handful in the -5 inches to -6 inches range, and most of those have been more recent. Check out the movement on this Triggs sinker. Have you seen many pitches like this one?

Your other top Ziegler prospect is Alex Claudio, like Ziegler also has an incredible and incredibly fun to watch changeup. He is waaaay more of a Ziegler than Triggs: of his 140 sinker/two-seamers this season, all but two have downward break. His average movement is -4.0 inches — the second-lowest mark among relievers with at least 50 sinkers, with Ziegler’s -6.7 average break the only total that looks more Ziegler.

Hitters don’t swing and miss at Claudio’s sinker (5.7% swings have been whiffs) as they do at Ziegler’s (16.3%), but as great a ground ball pitcher as Ziegler is (8.7 ground balls per fly ball on the sinker), Claudio has done something silly this year. Just 3% of Claudio’s balls in play off his sinker have been fly balls: he has had 28 ground balls per fly ball. That’s not a huge fluke, either: his career rate is over 15 to 1.

Just watch. Ziegler 2.0? The lefty?

3 Responses to Finding Another Brad Ziegler

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Starting 2022 with a frigid dog walk sounds just lovely https://t.co/xoLZSZBpGp, 23 hours ago

Starting 2022 with a frigid dog walk sounds just lovely https://t.co/xoLZSZBpGp, 23 hours ago I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30

I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30 Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29

Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29 Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27

Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27 Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Powered by: Web Designers

Nice article, very well done. Enjoyed it very much. I’m a DBACKS fan first and then my hometown A’s, so this was interesting.

It’s a amazing that a soft tossing sub mariner has become “must see” baseball every time he comes in. Keep in mind that Ziggy has been the biggest beneficiary of the low strike zone of any pitcher in baseball. He gets more calls at the bottom of the zone, (and below the zone) than just about anyone. But MLB is raising the strike zone next year from bottom of the knee to top of the knee. This potentially will have a huge impact on Ziggy, and SIMILAR pitchers. Taking the impending strike zone change into account, it’s possible the approach of trying to find another Ziegler is behind the curve.

[…] searching for pitchers with Brad Ziegler-like stuff, Alex Claudio bears a stark resemblance — except he does it from the left side. While he’s […]