What the D-backs Can Learn From the Giants

The Athletics, Rays, Pirates and Red Sox may get the lion’s share of the credit for experimentation at the major league level, but there is no group of teams that offers better lessons for the Diamondbacks than the group closest to home: the NL West. Last week, we looked for some takeaways from the Rockies’ experiences, as they are the team most similar to the D-backs. For slightly different reasons, the ball flies farther at both venues, and with similar budgets for much of their histories, the teams probably have a lot to learn from each other in terms of what hasn’t worked in the majors.

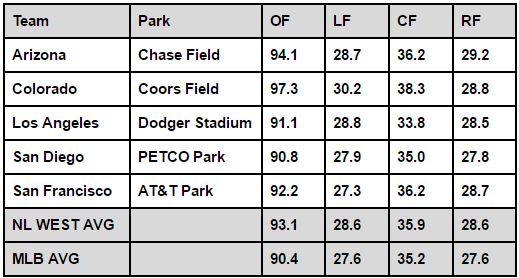

Today, we’re a little more focused on what has worked. As noted last week, while Colorado and Arizona have been the most extreme hitters’ parks in the majors, San Francisco and San Diego have been all the way at the other extreme. And yet NL West parks have one very important thing in common — including Dodger Stadium, which leans pitching as well. Before the 2015 season, Andrew Fox calculated the actual space in MLB park outfields. Here, in thousands of square feet:

It might surprise you to see PetCo and San Francisco so “small,” but remember — this is actual space in the outfield. The height of walls also matters, but much more to hitters than fielders. And it’s the fielders bit that makes this so interesting, I think. The NL West isn’t just on the large side — the average square footage in its outfields is 1,600 extra square feet more than any other division. There’s the NL West at 93.1 thousand square feet, then the AL Central (91.5), NL East (90.8), NL Central (89.8), AL West (89.3), and AL East (88.1).

With few exceptions, these days teams play 119 of 162 games in their division’s home parks (including their own). That’s nearly three-quarters of the time, thanks to baseball’s unbalanced schedule — tailoring your team to your division’s parks could be almost half as important as tailoring your team to your own. Many teams are not in a position to do both, but NL West teams certainly can; none of the outfields are small, and most of them are very big.

This may not seem like a big deal, but it sure as hell looks that way to me. In a large outfield, defensive skills are magnified, in any direction — poor fielders will affect the game more, and more poorly, while great fielders will affect the game more, and in a more positive way. The fielding prowess of one’s outfielders has very large consequences in the NL West, where outfields are abnormally and almost uniformly large. Roster priorities have to be flexible if your budget is not limitless, because sometimes the “wrong” skillset will be undervalued enough to become worthwhile.

We saw how the Rockies handled their strange field last week. Let’s see what we can glean from a success story — the Giants, winners of three of the last six World Series.

Lessons from San Francisco

Rockies lessons were in the nature of what not to do, mostly. But San Francisco provides some strong indications of what works in this division, and generally. It’s hard to stay in contention the way the Giants have, and harder still to win five championships in three years. Whether on purpose by accident, the Giants did something right in those years, or many things. We can learn from that.

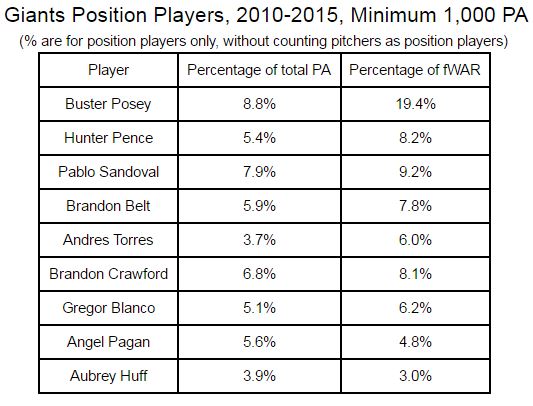

Let’s start with the large outfield phenomenon. In a large outfield, there’s nowhere for a poor fielder to hide — but there’s also room for a good fielder to excel. The Giants don’t contend with as large an outfield on a daily basis as the D-backs do, but it’s still large, and they play about 19 games a year in either Chase or Coors. I went back to teams’ total value stats from 2010-2015 (six full seasons) to see what the Giants’ secrets were. The value to the Giants of fringy outfielders that were strong defensively leapt off the page. See what I mean?

This group of nine position players had just 53.1% of the team’s non-pitcher plate appearances over our six year period, but 72.7% of its non-pitcher fWAR (I excluded pitchers from the totals, even as position players). That alone is not unusual at all for any team; I tried a few others. What’s unusual is how much of their value to the Giants came from defense, top to almost bottom.

And not a whole lot on offense. In this period of six years, there were four outfielders with 1,000+ PA, and none have exactly set the world on fire offensively: Hunter Pence (127 wRC+), Andres Torres (103 wRC+), Gregor Blanco (105 wRC+), and Angel Pagan (105 wRC+). As compared to their WARs, Pence is impressive, but the most impressive is probably… Torres.

Consider Blanco and Pagan, who illustrate what we’re getting at nicely. In terms of offensive value, they were exactly equal. Pagan played CF almost exclusively, whereas Blanco played about half his innings in the corner outfield spots. Because a competent CF is worth more than a competent RF or LF, Pagan gets a little bump in WAR by playing center — and yet while Blanco was clearly an asset with a share of WAR about 22% higher than his playing time share, Pagan’s share was about 14% lower than his playing time share. Blanco’s work in the outfield overall earned him a 9.2 UZR/150, well above average but not elite. Pagan’s work was -8.9 UZR/150, well below average but far from terrible. The difference between the two defensively was significant, but not enormous — and yet one helped to prop the team up into its championship caliber with 9.5 WAR in 1780 PA, whereas Pagan sputtered to a 7.3 WAR in 1,928 PA.

Consider Blanco and Pagan, who illustrate what we’re getting at nicely. In terms of offensive value, they were exactly equal. Pagan played CF almost exclusively, whereas Blanco played about half his innings in the corner outfield spots. Because a competent CF is worth more than a competent RF or LF, Pagan gets a little bump in WAR by playing center — and yet while Blanco was clearly an asset with a share of WAR about 22% higher than his playing time share, Pagan’s share was about 14% lower than his playing time share. Blanco’s work in the outfield overall earned him a 9.2 UZR/150, well above average but not elite. Pagan’s work was -8.9 UZR/150, well below average but far from terrible. The difference between the two defensively was significant, but not enormous — and yet one helped to prop the team up into its championship caliber with 9.5 WAR in 1780 PA, whereas Pagan sputtered to a 7.3 WAR in 1,928 PA.

Heck, Andres Torres contributed more WAR (9.1) in just 1,268 PA. Pence has graded just a hair below average defensively, but has done so in one of baseball’s most oddly shaped outfield zones, and by holding that line while taking advantage of the same dimensions at the plate, he’s more than earned his sizable contract. The best part? Players with a solid reputation like Pagan’s don’t come cheap. Most of his time in the period we’re looking at came on the free agent contract he signed at the end of 2012, a deal that is paying him $40M over four seasons. Players like Blanco, on the other hand, seem to grow on trees. Remember how Ender Inciarte surprised baseball with a 3.3 WAR performance in 2015 after putting up 2.8 WAR in a more limited role in 2014? That’s exactly the kind of player we’re talking about. And it’s not an isolated case.

Many of the finest recent defensive seasons by outfielders have come in especially large fields. Gerardo Parra‘s 2013 success in baseball’s 4th-largest RF is still one of the best defensive seasons on record by DRS at any position. Jason Heyward developed a reputation for being an excellent right fielder by patrolling the majors’ second-largest RF. Lorenzo Cain and Juan Lagares have enjoyed center fields over 36,000 square feet; Keven Kiermaier nearly broke defensive metrics last year while calling a 36,900 square foot CF his home. When Alex Gordon sparked a war over the viability of WAR with off-the-charts defensive numbers in left field in 2014, attention (including my own) was focused more on the low baseline against he was measured; the average left fielder is not a great fielder. But KC’s left field is also MLB’s largest.

The best example might be J.D. Drew, who was a pretty decent RF for the Cardinals (10th largest RF), an excellent one for the Braves (2nd), just slightly above average again with the Dodgers (8th), and excellent again with the Red Sox before age caught up with him (3rd). Defensive stats are said to control for park factors, but that’s a black box, and I don’t know how. But just like Nick Ahmed benefited from getting tons of balls in play and on the ground last year, you can’t fake opportunity — some fielders just get more chances.

But there’s a flip side. Aubrey Huff had to be hidden at first base during the Giants’ run — his suspect defense required it. Huff was just fine playing some right field for the Devil Rays (25.7 thousand square feet, 3rd-smallest) and Astros (26.6, 9th-smallest), but when the Giants tried using him at multiple positions in 2010, including both right and left, they learned their lesson pretty fast. Michael Morse‘s half-season in left in 2014 was an outright disaster.

But there’s a flip side. Aubrey Huff had to be hidden at first base during the Giants’ run — his suspect defense required it. Huff was just fine playing some right field for the Devil Rays (25.7 thousand square feet, 3rd-smallest) and Astros (26.6, 9th-smallest), but when the Giants tried using him at multiple positions in 2010, including both right and left, they learned their lesson pretty fast. Michael Morse‘s half-season in left in 2014 was an outright disaster.

And that makes sense — there’s no room to hide. Consider Fenway Park, and its famously small left field (a hilarious 21.1 thousand square feet, 9,100 square feet smaller than left at Coors). You actually can hide a hitter there without getting hurt too badly; Red Sox left fielders have gotten very awful grades by advanced defensive statistics, but it looks like that’s largely not their fault. There are just fewer balls they can field. For a team like the Red Sox, it’s smart to hide a good hitter in left if his defense has killed his market value. For a team like the D-backs, there’s nowhere to hide in the outfield, anywhere. There are so many smaller outfields in baseball that any outfielder who can’t be an asset defensively will definitely be more valuable to most other clubs than he is to Arizona. Or should be… I’m looking at you, Mark Trumbo, a post-surgery Cody Ross and a current Yasmany Tomas.

All that can sound like “save your money, spend it elsewhere than in the outfield,” and that’s another pretty good takeaway. But while power is always better than not-power, there is an opportunity here, as well — outfielders who don’t bring much power to the table can actually see their skills play up a ton in the large outfields of the NL West. Gregor Blanco had a tremendous home/road split in that 2010-2015 stretch for the Giants: a 123 wRC+ in home games, fringy 88 wRC+ in away games. Hunter Pence had seasons of only somewhat above average offense with the Astros, hitting exactly 25 home runs in three consecutive seasons there; the seasons he spent only with the Giants show wRC+s of 135, 124, 127 and (this season) 140. Andres Torres had a 128 wRC+ at home, but a mediocre 78 wRC+ in away games.

This has not been an isolated phenomenon, and it’s not limited to outfielders, either. The Giants are first in the majors from 2010-2015 in position player WAR, and in the same stretch, they have the third-lowest strikeout rate among hitters (17.3%), and the second-lowest HR total (744). The most extreme team in both categories, by the way, is the Royals — another team that plays in a large-OF environment. Contact hitters play up in large outfield parks. Sometimes it can seem like the right answer is to collect players with bigger power, but that’s just not the case, it seems. The Giants reaped enormous rewards with a contact-oriented offense. The application for the D-backs is not quite so obvious, there, since like Coors, Chase encourages home runs more than average, while encouraging other base hits, as well. Chase is a lot closer to average, though, and the theory should hold here. Contact hitters will get more hits (hello, Jean Segura!). If you can favor defense (one of baseball’s cheaper commodities) while focusing on contact hitting (another one), you can get a valuable player for you in the NL West without paying incredible sums.

This has not been an isolated phenomenon, and it’s not limited to outfielders, either. The Giants are first in the majors from 2010-2015 in position player WAR, and in the same stretch, they have the third-lowest strikeout rate among hitters (17.3%), and the second-lowest HR total (744). The most extreme team in both categories, by the way, is the Royals — another team that plays in a large-OF environment. Contact hitters play up in large outfield parks. Sometimes it can seem like the right answer is to collect players with bigger power, but that’s just not the case, it seems. The Giants reaped enormous rewards with a contact-oriented offense. The application for the D-backs is not quite so obvious, there, since like Coors, Chase encourages home runs more than average, while encouraging other base hits, as well. Chase is a lot closer to average, though, and the theory should hold here. Contact hitters will get more hits (hello, Jean Segura!). If you can favor defense (one of baseball’s cheaper commodities) while focusing on contact hitting (another one), you can get a valuable player for you in the NL West without paying incredible sums.

You can’t pick your opponents’ lineups, but you can pick your own pitching staff, over time. Seeming to acknowledge AT&T Park’s helpfulness for contact hitters, the Giants countered the effect of their home park and those of the NL West with strikeout pitchers. While maintaining that 3rd-lowest strikeout rate on the hitting side, the Giants maintained the 4th-highest strikeout rate on the pitching side. Talk about taking advantage in just the right way. With their 20.6% K% in our six-year span, the Giants had baseball’s fifth-lowest ERA. A staff that shies away from encouraging soft contact can often get burned by home runs, but again, that played to the strength of the Giants’ home park. AT&T and the NL West also provided an especially friendly place for Matt Cain to be a unicorn, a starting pitcher with a fly ball rate so high it became an asset. We’re starting to see with Tyler Clippard that that might even extend to a venue that doesn’t exactly discourage home runs, through sheer outfield size. There’s reason to think this approach worked not just because of the homer-reducing effects of AT&T, but because of the outfield’s size — it could extend to the D-backs and Chase Field, as well. During this 2010-2015 stretch, the Giants had a 3.20 ERA at home, but a 3.80 ERA at Chase Field — still better than their 3.96 ERA at all other NL parks. Somehow, the Giants also enjoyed an advantage at Chase Field with their pitching staff.

You can’t pick your opponents’ lineups, but you can pick your own pitching staff, over time. Seeming to acknowledge AT&T Park’s helpfulness for contact hitters, the Giants countered the effect of their home park and those of the NL West with strikeout pitchers. While maintaining that 3rd-lowest strikeout rate on the hitting side, the Giants maintained the 4th-highest strikeout rate on the pitching side. Talk about taking advantage in just the right way. With their 20.6% K% in our six-year span, the Giants had baseball’s fifth-lowest ERA. A staff that shies away from encouraging soft contact can often get burned by home runs, but again, that played to the strength of the Giants’ home park. AT&T and the NL West also provided an especially friendly place for Matt Cain to be a unicorn, a starting pitcher with a fly ball rate so high it became an asset. We’re starting to see with Tyler Clippard that that might even extend to a venue that doesn’t exactly discourage home runs, through sheer outfield size. There’s reason to think this approach worked not just because of the homer-reducing effects of AT&T, but because of the outfield’s size — it could extend to the D-backs and Chase Field, as well. During this 2010-2015 stretch, the Giants had a 3.20 ERA at home, but a 3.80 ERA at Chase Field — still better than their 3.96 ERA at all other NL parks. Somehow, the Giants also enjoyed an advantage at Chase Field with their pitching staff.

I’ve buried the lede, and I’m sorry. You saw it in the Giants table above, and were shocked we didn’t address it then and there. Buster Posey‘s share of his team’s position-player WAR is a whopping 220% of his share of the plate appearances. And that’s where the genius of the San Francisco approach to roster construction starts to look like a combination of shrewd moves and divine intervention. The truth is, Buster Posey’s 29.6 fWAR in our six-year stretch still undercounts his value. The best statistics for catcher framing in the world come from Baseball Prospectus, and with those numbers added to the mix, Posey’s worth is estimated at 37.9 wins (WARP).

Overall, Posey just made his pitching staff better. Take 2014, the Giants’ most recent championship season, as an example. Baseball Prospectus credited Posey with 23.6 runs’ worth of value just through framing, over and above the average catcher (not a replacement level catcher). The other parts of his defensive game (the parts more accurately counted in fWAR) pushed him to 24.2 runs of value through defense that year. The Giants pitching staff finished with a 3.50 ERA that season, 10th in baseball. If Posey had contributed merely average work behind the dish, that would have risen to 3.66. If he was somewhat below average defensively (-10 runs), the staff’s ERA could have been 3.72. It’s not like Posey made one of the majors’ worst staffs one of the best, but that’s still an incredible difference.

Overall, Posey just made his pitching staff better. Take 2014, the Giants’ most recent championship season, as an example. Baseball Prospectus credited Posey with 23.6 runs’ worth of value just through framing, over and above the average catcher (not a replacement level catcher). The other parts of his defensive game (the parts more accurately counted in fWAR) pushed him to 24.2 runs of value through defense that year. The Giants pitching staff finished with a 3.50 ERA that season, 10th in baseball. If Posey had contributed merely average work behind the dish, that would have risen to 3.66. If he was somewhat below average defensively (-10 runs), the staff’s ERA could have been 3.72. It’s not like Posey made one of the majors’ worst staffs one of the best, but that’s still an incredible difference.

And think of how the catching lesson complements the pitching lesson. Excellent work as a sequencer behind the plate (we have no stats for that — keep that in mind) could help with everything: whiffs, walks, but also soft contact. Excellent work as a pitch framer can help keep a pitcher away from the center of the plate, which could also limit hard contact to an extent. More than anything else, though, framing is about stealing strikes — about strikeouts. And that just happens to be the thing that seems to have made the Giants especially effective in their home park and the NL West. Buster Posey was the perfect keystone to the Giants’ roster construction. Buster Poseys don’t grow on trees. But if strikeouts are especially important at Chase Field — and I think that’s as true as it is at AT&T — it stands to reason that an especially good framer could still be especially helpful. And a good framer is pretty damned helpful to start with.

It all snowballs together. If you have a large outfield that limits home runs and encourages other extra base hits, contact hitters are great, and contact-oriented players who are strong defenders aren’t especially expensive, thanks to some of baseball’s biggest payrolls being dedicated to some of baseball’s smallest parks. There’s a huge effect there for outfielders, but defense-first contact-oriented hitters also play up in the infield. All of that makes for a strong defense, making the pitching staff better. And if all that saved money and a great framing catcher turn good pitchers into great strikeout pitchers, the pitching staff is in an especially good position to capitalize on their home park. It all fits together.

It doesn’t all necessarily apply to the D-backs. There’s a wrinkle — power still means something more. But I think we’re seeing from Jake Lamb the way we saw it from Paul Goldschmidt — doubles-oriented hitters are great fits for the D-backs and Chase Field. If you can fill out the roster with contact-oriented hitters who are good defenders, you put yourself in a position to gain two big advantages from your home park (and, really, the entire NL West), in terms of reaping more defensive value than a good-defense team would in a small park, and seeing hitters spray the ball all over the outfield to places that few outfield crews can cover especially well. It comes down to pitching, and the fact that strikeout pitching is expensive everywhere. If the D-backs can just find themselves an excellent catcher who helps the staff with framing, he doesn’t need to be Buster Posey to help turn the home field tide to the D-backs’ advantage — he can be just another one of those hitters who use the large Chase confines to collect a few extra hits.

7 Responses to What the D-backs Can Learn From the Giants

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

#Ballislife https://t.co/Dg8I9iqcNY, Feb 09

#Ballislife https://t.co/Dg8I9iqcNY, Feb 09 I watched three innings of live, in-person baseball today. It was cold. It rained. The teams weren't good. And it was glorious!, Feb 08

I watched three innings of live, in-person baseball today. It was cold. It rained. The teams weren't good. And it was glorious!, Feb 08 This badass, of course https://t.co/c7MarsDwc7 https://t.co/Atc7qIwE7J, Feb 08

This badass, of course https://t.co/c7MarsDwc7 https://t.co/Atc7qIwE7J, Feb 08 RT @AdamCMacK: Man, it is too much fun doing this. Getting to hang with @OutfieldGrass24 and @bdentrek was so much fun. I am very… https://t.co/5grMtRdz7P, Feb 08

RT @AdamCMacK: Man, it is too much fun doing this. Getting to hang with @OutfieldGrass24 and @bdentrek was so much fun. I am very… https://t.co/5grMtRdz7P, Feb 08 RT @sydrpfp: My first @baseballpro feature: What can baseball learn from teachers about organizing and collective action? https://t.co/f2cg93ZhRE, May 28

RT @sydrpfp: My first @baseballpro feature: What can baseball learn from teachers about organizing and collective action? https://t.co/f2cg93ZhRE, May 28

Powered by: Web Designers

Wonderful article. Unfortunately the Dbacks’ last two FOs don’t exactly seem to have learned these lessons, having traded away great defensive, contact-oriented outfielders in Eaton and Inciarte, and treating us to the spectacles of Kubel, Trumbo, Tomas, and now O’Brien in the corners. I think many fans can be fooled into thinking those guys are alright if they don’t make many errors, but it’s all the balls they *don’t* get to that make a big difference, not to mention all the balls they don’t put into play with their high-K approach.

If Brito keeps developing, I’d love to see him, Pollock, and Peralta in the outfield in 2017. That would be close to the sort of group you are asking for. What to do with Tomas, O’Brien, and Drury would then become the question. I have hopes that Drury could become a decent corner outfielder, defensively, since he’s a fine athlete. And he should be a higher-contact guy than we saw in May and June, so he’s the guy I would most like to keep around among that group of three. Doesn’t hurt that he can also give you good innings at 3B and some at 2B. The other guys are just so limited and bring extra negative value from their plodding baserunning.

But as I said, this FO doesn’t seem to get that (note that Hale said Drury would play the infield at Reno, not the outfield). Which sort of surprises me, given how TLR’s Cardinals were often constructed.

The one thing that seems certain is that a Tomas, Peralta, O’Brien outfield, which thankfully we haven’t seen much of, would be about the worst way to match skills with the ballparks the Dbacks play in.

To be fair, we’re all still learning — I feel like I understand a lot more now than I did even at the time of the Inciarte decision (and that predated the trade by a little bit). I do feel that things keep getting clearer, but I know there’s a lot more we can understand better, too.

When the Red Sox traded for Adrian Gonzalez, I was one of the many people who thought “Geez, if he can hit that many at PetCo, how many more will he hit at Fenway?” — and now I know better, I think. I thought the (first) Trumbo trade was terrible at the time, but even then, I did think Trumbo’s power would play up at Chase. Alas, the kind of trade that Trumbo makes, sacrificing contact for bigger power, works fairly well, but only at 28 ballparks. In a small park, over the fence offers a bigger reward than “in the outfield somewhere,” and in your average large park, that’s the price of actually getting over the fence. But here… it just doesn’t make sense. You want doubles power that takes advantage of these enormous outfield gaps, not just at Chase, but (and I only now really appreciate this) all over the NL West. The benefit of the approach that Goldy and Lamb have, where they still make tons of contact in the 98-106 mph range, is that at Chase Field, that actually turns into more home runs, too. They’re a perfect fit.

It’s too bad that O’Brien is probably worth less to the D-backs than to other teams, but, hey — that’s what trades are for.

I agree with you, though. Kubel was probably all we needed to learn our lesson. The evidence is all there, though, now. Not just in how guys like Pollock and Inciarte have done so damned well, but Kubel, the difference between pre- and post-surgery Cody Ross, Trumbo…and probably Tomas, too. Agree 100% with your last point.

Let’s see if Owings can do a great Inciarte impression after more outfield work — he could be a pretty great 4th OF. I’d like to see what he looks like getting regular starts in the corners.

Owings and Drury as guys who could move around the diamond, give you depth, and always play v. lefties wouldn’t be a bad idea.

On the FO, while it may not have been clear a few years ago just how the outfields in the NL West played, at a simpler level it *was* clear that defense and baserunning mattered, and they have fairly consistently prioritized slow, low-OBP guys who can hit Dingerz instead. That’s what’s irritating.

I’ll take over this website and do it justice if you guys can convince dbacks ownership to hire you and remove stewart. I’ve never managed a blog or webpage, but stewart has never gm’d a ball club before, and he’s making gobs of money. It’s just crazy to me, all the new info that comes out (ie total outfield square footage) and I can just imagine stewart talking with his staff about how obrien just needs time to learn out there, and how its okay because tomas is capable of 20 hrs. Someone tells him the total outfield square footage and he thinks it’s a useless saber statistic. You guys, on the other, conduct awesome research that is truly valuable. This website is about the only thing that gives me hope when it comes to baseball in az. The fact that there are solutions that can be ascertained, even though contracts and players will not always pan out, is so cool. And i know, i know, ‘everyone thinks they can run a baseball team using statistics and thats just not how its done’ etc etc. I get it. The dbacks have been managed poorly at times, and weve made some astute moves at times, but the point is, its been years of management that lags behind our division rivals, and THAT’S who we need to beat. The dbacks front office isn’t totally incompetant. It just seems that, too often, they’re looking for solutions to the wrong problems.

Next do an entry about all the times Chip Hale has praised the team for failing. I just want to see all the quotes strung together.

Nice work on this article again, as per usual.

Ryan — Thanks a ton for this comment, much appreciated. We love thinking about this stuff.

Over two years ago, I wrote a piece advocating for an analytics department. A lot still applies. We have an analytics department now, but there’s still something missing, I think — and it’s in the last section of that piece.

I’m lucky to be in a fairly small law office (6 attorneys) with great work, a small number of cases with public interest consequences and high value. We don’t always agree, here. But when we don’t, we sometimes have it out, arguments that could look pretty ugly on the outside, but that no one here takes personally. If I disagree with an approach, I have that opportunity for persuasion. The burden of persuasion is mine, in that context — but I have the opportunity.

I think these are the things a great analytics department would have:

1. Top-notch math, science, and database skills.

2. Good resources, especially access to top-of-the-line information. There’s proprietary stuff out there, and tons of raw data delivered to clubs now from Statcast.

3. A great director to solve problems and determine how resources (mostly: time) are spent.

4. An understanding of the state of public research, everywhere else. Especially important in the manager position.

5. A good working relationship with the club’s ultimate decision-makers in baseball ops.

6. The ability to assign itself work — to ask and answer its own questions, rather than just answering questions assigned by ops.

7. The opportunity to persuade, without consequences. Feeling welcome to disagree.

8. The ability to persuade, when appropriate.

I have no idea on the extent to which the D-backs’ department can claim these things, although I think #1 is true. My suspicion, though, is that we’re lacking in #6 and #7.

Several years ago, the old school Royals started an analytics department with a really talented group. Knowing that, for a few years I really doubted their power to influence their organization — the team kept zeroing in on old school types. Omar Infante? Really, Lorenzo Cain and Alcides Escobar as the centerpieces for two years of Zack Greinke? Jason Vargas???

With the benefit of hindsight, it sure as hell looks like there’s been a pretty great working relationship in KC, in part because of the subject we tackled first above — Kauffman Stadium’s outfield is ENORMOUS (even larger than Coors, slightly). We all know that some outfields are big, and some — especially Fenway — are small. But does anyone appreciate what it means that Kauffman has 12,300 more square footage in its outfield than Progressive Field, in the same division?

The Royals focused on contact hitters (check), prioritized defense in the outfield, even at the corners (check), and targeted starting pitchers they could rely on to get them deep into games: Vargas, Edinson Volquez, and most recently, Ian Kennedy with a 5 year, $70M deal just over two years after he was essentially cast aside by the D-backs. What a great strategy, right? This year, the Royals rotation has the highest fly ball percentage in the majors (40.3%). Perfect. The whole god damn roster is built around one interlocking, snowballing strategy.

That’s what I want for the Diamondbacks, and I think you do, too. Our job here is not as straightforward as that of the Royals, but letting the best overall strategy inform (but not dictate) ALL roster decisions is not too hard to achieve.

[…] may not be the best fit for a place like Chase Field to begin with. As my esteemed colleague Ryan pointed out just last week, the NL West is full of big outfields, providing extra fielding challenges for a lumbering slugger. […]

[…] hitting the ball hard to all fields and taking advantage of Chase Field’s large dimensions. We’ve talked about the merits of this approach before, and now that a humidor will be in play, line drives may become even more valuable at […]