Low and Away Explains Some D-backs’ Seasons at the Plate

Want to flummox one of baseball’s best offenses? Try pitching low and away. It seems obvious, and it’s probably true of most teams, to some degree. But only three teams struck out at a higher rate on those pitches than did the D-backs — a 19.4% K rate is not very good. They’ve also avoided doing big time damage in that sector of the plate, with a ratio of AB to HR of 299.5, the worst in the majors. On the other end of the spectrum are a handful of teams that have done surprisingly well this year and teams with a reputation for being “smart.” Are you interested yet? Did the D-backs succeed despite a weakness that could maybe be addressed? Or did they somehow succeed because of it?

I’m sorry: it’s both, kind of. That’s the trouble with team-wide hitting statistics. On the pitching side, that kind of thing can reveal a strategy, or at least a set of priorities; but unless something is clearly not right, teams tend toward a hands-off approach for their hitters (except for Chris Owings, for whom the D-backs had a “two hands on” approach) (sorry again). As it happens, the D-backs are pretty bad at reaching low and away strikes. But there’s a variety of reasons for that, and only some guys are getting beat that way.

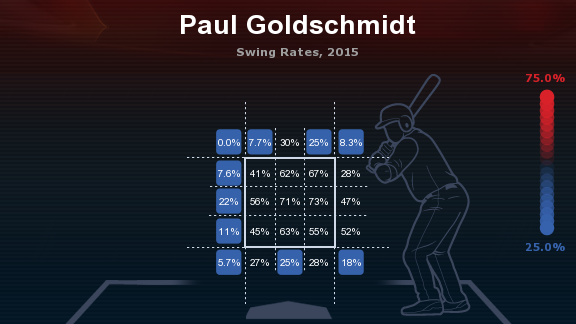

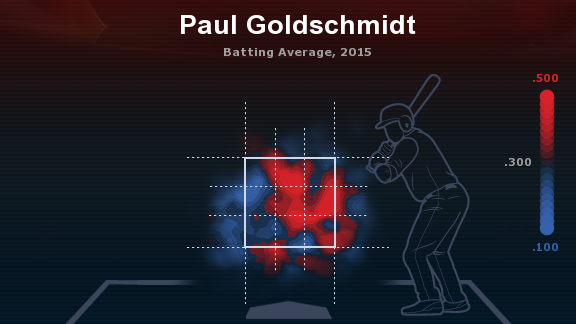

Case in point: Paul Goldschmidt. When he first came up, Goldy dominated the inside third of the plate; but it wasn’t until he dominated the whole top of the zone, as well, that he broke out in 2013. Things are not so dire in 2015 as when he hit just .197 low and away in 2013, but it’s not like low and away was a big strength this season. From ESPN Stats & Info:

Away may be a weakness for Goldy in general, but it’s not like his results this season made it look like he had any weakness. A big part of that: not swinging. Compare the heat map above with this chart of swing rates:

Just as Goldy doesn’t really swing at curveballs, the pitch against which he’s struggled, he also doesn’t let himself get beat down and away. He’d much rather just not swing. That gets him a long way, as we can infer; although the cutoff between “swing” and “not swing” away on the plate versus away off the plate is pretty staggering. The guy knows what he’s doing.

That 19.4% strikeout rate for the team low and away is definitely pretty bad, but league average is still 17.2%. We’re talking just 13 strikeouts, or fewer than one per ten games. Not swinging down and away occasionally means an extra walk for Goldy; but it also means more pitches to hit. A weak ball in play is not better than a called strike, unless there are two strikes already. And for what it’s worth, Goldy’s swing rate in that section of the zone rises to 85% with two strikes. With one strike, it’s 41%; with no strikes, it’s just 24%.

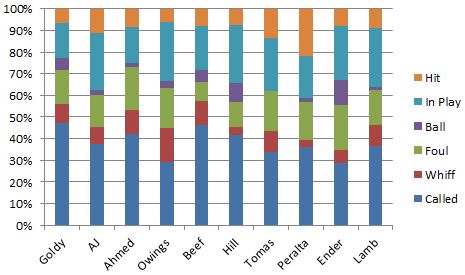

Goldy’s not the only one with a plan that makes for some limited success low and away. From Baseball Savant, here are the pitch-by-pitch results for the D-backs hitters who were vaguely full time for a big part of the season:

More than many of the things I’ve looked at, this low-and-away breakdown seems to tell us a lot about the 2015 season. As noted, Goldy watches a ton of called strikes down and away, seemingly by choice. Chris Owings puts a ton in play, but has extremely little to show for it — he might do well to take a page from Goldy’s book and just let the umpire hoot or holler when a pitch comes in low and away with fewer than two strikes. Aaron Hill hasn’t missed, but hasn’t done too much with those pitches either. You can’t sneak one by Ender Inciarte, and once again, Yasmany Tomas has surprising success there — in part because he doesn’t see any pitches in the zone that he doesn’t like, and in part because he’s had success shooting the ball the other way.

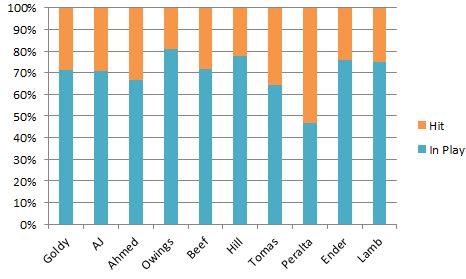

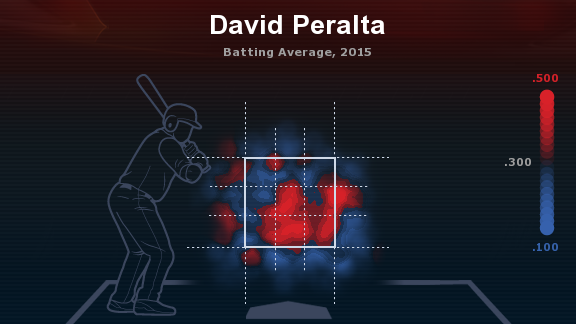

The one that stands out most, though, may be David Peralta. Let’s try a similar graph, instead focusing only on balls hit in play, whether for a hit (that’s the orange above) or an out (that’s the… teal?).

Only three of these guys have managed to get hits at least 30% of the time they’ve put a low-and-away pitch into the field. It’s not quite BABIP since this includes home runs, but still: kudos on what is essentially a .333 BABIP for Nick Ahmed, and a .357 BABIP for Tomas. The same number for Peralta: .531.

And we’re not talking a small sample, exactly. This is of 114 pitches, 22 of which were outs in play, and 25 of which became hits. Unlike Goldy, who’s racked up some hits by trying to not do his business low and away, that’s where Peralta has become a successful entrepreneur. And while swinging as hard as Peralta does normally means missing more often — and while swinging at something farther away does normally mean missing more often (try holding a hammer with just the very bottom of the handle)… Peralta has swung at a down-and-away pitch in the zone 71 times, and whiffed just 4 times. A 5.6% whiff rate. It may be that few players, even in MLB, can replicate Peralta’s bat speed. But this 2015 season wasn’t all about running into some balls; this man has “precision” among the tools in his toolsy profile. Low and away is a big part of Peralta’s game. From ESPN Stats & Info again:

So Goldy’s numbers low and away aren’t terribly impressive, in part because he knows to hold out for something better when he can. Peralta’s are — but his strikeout rate is still fairly significant — in part because that is something better for him and his full-on, full-extension swing.

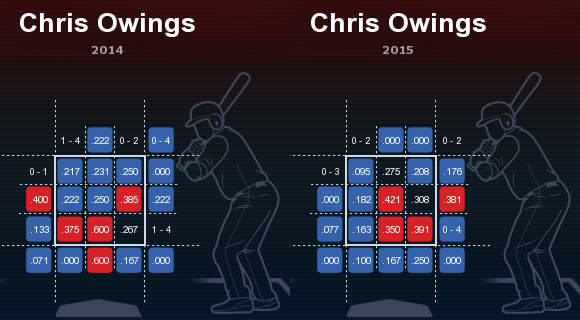

Chris Owings has hit just .227 for the season — including just .163 low and away. I’m no scout, but switching to a two-handed finish could help explain a lesser ability to do something with those pitches. Owings is probably never going to get great plate coverage high in the zone. But look at the difference between his 2014 and 2015 in that section of the zone, in terms of batting average:

Pretty significant, from a strength to a liability. Every hitter owns the center of the plate. Grab three of the corners as well, and you can do some great things; two, maybe you can hit at a league average clip. Plant a flag in just one corner, though, and you’ve got yourself a problem.

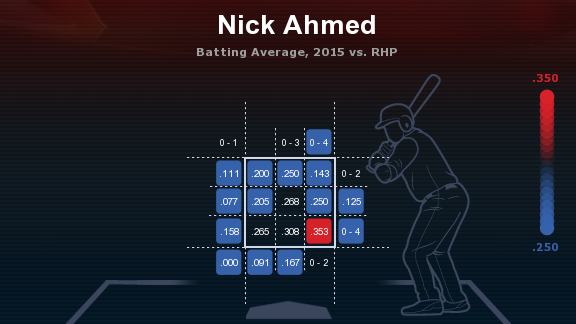

The “one corner” phenomenon has also been a problem for Nick Ahmed, and as with Owings, the corner he’s claimed is low and away. Ahmed has a lot of arm. He’s down better down in the zone overall, but has gotten beat both up and in and down and away. Check out his results this year against right-handed pitchers:

It’s not a very big flag. But as you’ll recall, Ahmed’s RHP struggles didn’t translate to similar problems against lefties. In the end, Ahmed finished the season with a well below average 50 wRC+, meaning he generated offense at a rate 50% below league average. The contrast with the 115 wRC+ he managed against lefties is stark — he was a somewhat better than average hitter against lefties this season.

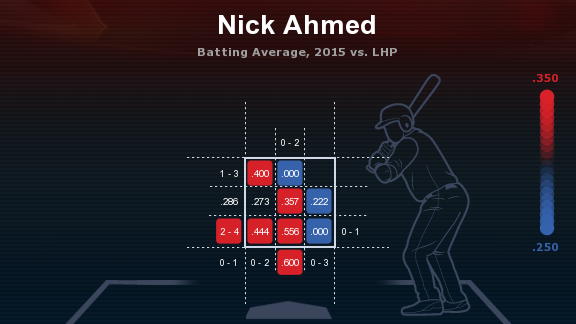

What’s that you say? Somewhat better than average? Sounds like someone who’d claimed two corners of the plate, with maybe a little bonus coverage to boot. Against lefties:

Just a completely different guy. Some evidence that Ahmed was able to decide to lay off those up and in pitches that gave him and his long arms so much trouble against RHP; southpaws foolishly threw low and away to Ahmed all season, but there were still plenty of pitches up and in, and Ahmed’s swing rate up there all but vanished. And Ahmed completely owned that low and away section of the strike zone.

Low and away isn’t everything, but it sure seems to make a big difference in at least some cases. I think the overall struggles of the D-backs in that sector, though, are not a reason to raise an alarm. For some guys like Owings, Ahmed and Jake Lamb, there’s no place in the zone that offers more room for improvement; and yet for others, the team’s overall numbers are just a reflection of what they’re doing well.

3 Responses to Low and Away Explains Some D-backs’ Seasons at the Plate

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Starting 2022 with a frigid dog walk sounds just lovely https://t.co/xoLZSZBpGp, Jan 01

Starting 2022 with a frigid dog walk sounds just lovely https://t.co/xoLZSZBpGp, Jan 01 I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30

I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30 Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29

Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29 Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27

Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27 Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Powered by: Web Designers

This is fantastic! A full-team breakdown and really reveals some major successes (Peralta and his opposite-field triples, Goldy’s patience) and major struggles (Owings’ inability to reach across the plate, Ahmed v. RHP’s).

This makes me think of Eno Sarris’ piece at FG’s last week when he spoke with Zack Greinke about pitching inside (http://www.fangraphs.com/blogs/zack-greinke-on-pitching-inside/). Guys are going to get worked low-and-away, and if they don’t find a way to punish pitches there, they’ll never coax anything into a more palatable part of the strike zone. The best hitters either have approach for both hard-inside and low-and-away, or learn to lay off what they can’t punish. The D-backs have examples of each, apparently.

One simple explanation might be that the D-Backs have less left-handed hitters than most other teams.

More right handed hitters means more down and away pitches from right handed pitchers. Most teams have more right handed starters than left….

The solution may simply be to get more left handed (or switch) hitters, so they won’t have to face all those right handed pitchers.

[…] don’t remember what I’m talking about. By the end of the season, it still looked like low and away was Owings’s undoing last year, and full extension probably should be harder if you’re gripping the bat hard with that […]