Tyler Clippard: Splitting the Difference

There’s been more failure than success for D-backs pitchers recently (6.4 runs allowed per game, last 12 games), but a handful of pitchers have seemed immune. Brad Ziegler has kept up his old tricks, and while the reasons are interesting — we all know how he does it. Tyler Clippard is just as fascinating, however — and while he could be fairly described as “Bizarro Ziegler,” there’s reason to think Clippard’s brand of success may be just as sustainable.

Clippard’s 3.16 ERA to date doesn’t shout “bullpen savior,” necessarily, but consider how steady he’s really been. Entering the game mostly at the beginning of an inning for his 34 appearances, he’s yielded earned runs just 8 times — and more than one run just twice. A fly ball pitcher as extreme as they come, Clippard has been a little homer prone — a trait that seemed to come to the surface in early June, when he allowed three home runs (of five total) in just four appearances. With 70+ innings in six straight years before 2016, Clippard has been a human metronome in the majors — and since relievers can’t do side work, if you’re going to lock up roster spots with relievers you can’t option, a reliever like Clippard is the best case scenario.

A string of similar results does not mean that Clippard has worked his way through his career the same way, however. When he came up as a starter prospect for the Yankees in 2007, he was a fourseam/curve/change guy, the kind of pitch mix that helps to inoculate a pitcher from platoon splits. Clippard stalled some in the minors after being traded to the Nationals, however, and when they converted him to relief in 2009, everything changed. You can keep a 4.66 ERA starter in the minors without batting an eyelash, but a 0.92 ERA reliever will find his way to the majors.

It’s been gangbusters since then: including the back half of the 2009 season, Clippard has thrown 556 innings of 2.70 ERA baseball in the equivalent of just over seven seasons. But as a reliever in 2009, Clippard downplayed the curveball part of his fourseam/curve/change repertoire, throwing some cutters that limited hard contact. In 2012, his worst season as a reliever, that cutter didn’t do as well, and his biggest drop in curveball usage seemed to have a price. In 2013, he leaned back into the curve, started to move away from the cutter, and introduced a splitter at the end of the season. In 2013, the splitter took the spot of the cutter, completely. And in 2015 while dealing with a dip in velocity, Clippard moved from a fourseam/curve/change/split repertoire to a five-pitch mix, adding a brand new slider.

Clippard’s fourseam happens to be one with tremendous vertical movement and very little going on horizontally; it’s the main reason he’s been a fly ball pitcher. The curveball happens to be one that drops almost straight down. And although many pitchers’ changeups tend to be ground ball pitches, in part because hitters tend to be early and in part because they tend to drop, Clippard’s change has more “rise” than most pitchers’ fastballs.

Clippard’s fourseam happens to be one with tremendous vertical movement and very little going on horizontally; it’s the main reason he’s been a fly ball pitcher. The curveball happens to be one that drops almost straight down. And although many pitchers’ changeups tend to be ground ball pitches, in part because hitters tend to be early and in part because they tend to drop, Clippard’s change has more “rise” than most pitchers’ fastballs.

In taking a look at D-backs right-handed relievers to examine platoon splits, we saw that Clippard’s mix in 2015 resulted in astonishing results against lefties, while he was merely good against righties:

Not all pitches are equal here — last year, Clippard barely threw that curve, and was mostly a four-seam/change guy against everyone. He threw his slider and split each 7%-8% of the time, and their effectiveness probably has a lot to do with how infrequently they’re used. They don’t really get mixed in more against batters from one side of the plate or the other; what changes is… the change. Clippard threw his changeup 45.3% of the time to lefties last year, more than he threw his actual fastball. Against RHH, he threw it “only” 31.4% of the time.

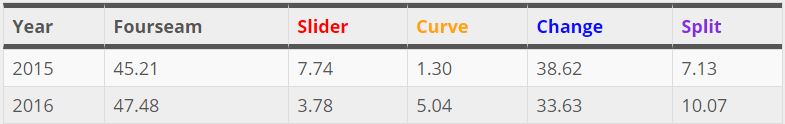

This season, Clippard’s pitch mix has been about the same as 2015, although he’s made some minor adjustments:

The movement on Clippard’s pitches is almost identical to last year (graphic above), with the minor exception of his splitter walking a bit to his arm side (about two inches), at the cost of just under an inch of drop. And the splitter does drop. This season, just 35 pitchers in the majors have thrown at least 50 splitters, according to Brooks Baseball and Pitch Info — and only Detroit’s Mike Pelfrey (-0.94 inches vertical movement) has had more average drop than Clippard (-0.80). In fact, just three of the 35 pitchers have an average vertical movement on the pitch of less than zero.

Clippard’s split has been the most dominating of those three, by far. Only the Pirates’ Arquimedes Caminero has a higher whiff rate on the split than Clippard’s 50% — and Caminero throws the pitch over 91 mph, as both Jean Segura and Nick Ahmed unhappily experienced earlier this season. The really fun part of Clippard’s split has been the batted ball numbers. Baseball’s most extreme fly ball pitcher has an extreme ground ball pitch.

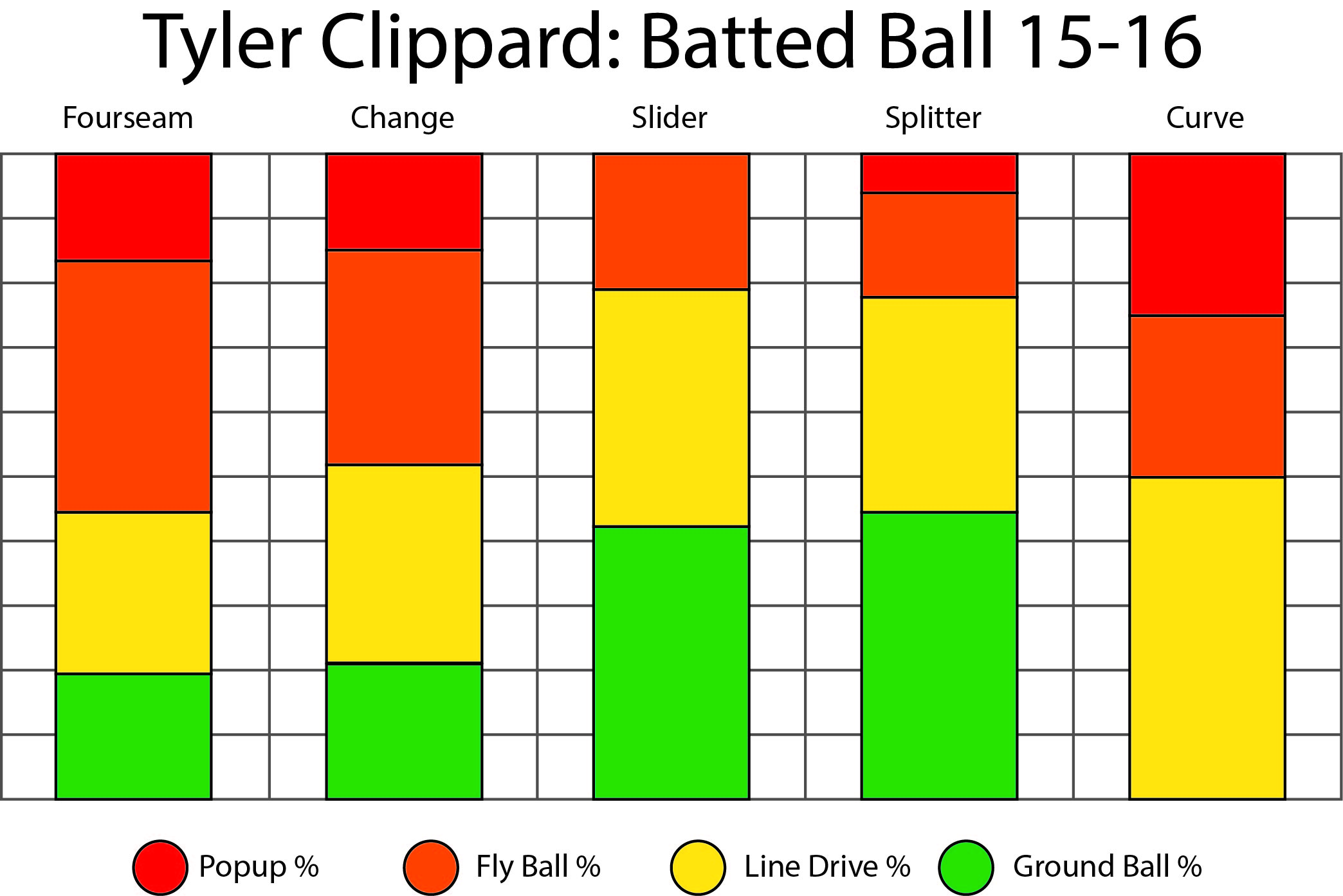

In the last two seasons, Clippard’s batted ball rates have been a study in extremes:

By taking a look at these batted ball rates, you can get an idea of how batters miss. Generally speaking, batted ball rates will look like they’re roughly in thirds, with popups a (usually quite small) part of the fly ball third. The rates on Clippard’s fourseam and change are nearly identical, with ground balls way down, fly balls way up, and a ridiculous number of popups. Clippard’s slider and splitter have oversized ground ball rates, suggesting that if we had more than one category for ground balls as we do for fly balls (the ground ball opposite of a popup), we’d be seeing a whole bunch of those. The curve has been Clippard’s least-used pitch (45 in last two seasons), and it’s rarely put into play (4 times).

Clippard is mostly an extreme fly ball guy, and that’s the way it’s likely to stay. But overall, he’s no longer the leader, let alone an outlier — his 44.7% FB% ranks just 22nd among 157 qualified relievers. That would be alarming — pitchers only tend to succeed on the extreme ends of FB% and GB%, if they rely on contact management to get their jobs done. What we’ve got here, though, is a version of Clippard who is still very much his old self — his 55% FB% on his fastball and 49% FB% on his change tell you that. With increased usage of his slider and split, though, Clippard isn’t just Clippard — he’s also got some Ziegler in him. He’s an extreme fly ball pitcher and an extreme ground ball pitcher.

That should give you some confidence that Clippard can change with the times, if his fastball were to slip; despite being Ziegler’s polar opposite in many ways, Clippard was actually one of a handful of pitchers who I found when looking for another Ziegler — because in the splitter, he has a pitch that could potentially make him one. We’re on the lookout for things that work at Chase Field, and Clippard has taught us two important things. One: it’s taught us that an extreme fly ball approach can possibly work at Chase, perhaps in part because the pitcher also gets to enjoy PETCO, Dodger Stadium and AT&T Park. But two: it’s taught us that the splitter might be a pitch that works especially well.

The Kevin Towers Era and its wake brought us some pretty awful relievers, Addison Reeds and Heath Bells who had no extreme batted ball tendency, but who did strike guys out more often than most. They seemed to get burned by anything. Before the wheels came off in 2014, however, the D-backs did get a reliable veteran arm in J.J. Putz, who managed three consecutive seasons of relative greatness, 2011-2013. His signature pitch? A splitter. Packaged with a strong and fairly vertical fourseam fastball and a hot sinker that averaged around 93 mph, Putz’s splitter formed a troika of pain that actually worked at Chase.

Clippard seems to be tapping into the same thing. Note that his split has had a healthy popup rate in addition to the heavy ground ball results — that’s a pretty good indication that hitters are having a hard time squaring him up. Add to that: only 9 batted splitters have velocities tracked by Statcast this season, and 6 are under 90 mph (the great zone for a pitcher), and the others are still under 98 mph (with 98-108 mph being the happy exit velo area that makes Paul Goldschmidt and Jake Lamb so great at Chase). Clippard may be onto something here — or it might just be too early to tell. Either way, it sure seems like Clippard’s continued success could have a lot to do with that split — even though he really doesn’t throw it that much.

One Response to Tyler Clippard: Splitting the Difference

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

#Dbacks' 2018 1st round pick Matt McLain hit .203/.276/.355 as a freshman at UCLA last year. This season? A tidy li… https://t.co/yM48j1ebrr, Mar 07

#Dbacks' 2018 1st round pick Matt McLain hit .203/.276/.355 as a freshman at UCLA last year. This season? A tidy li… https://t.co/yM48j1ebrr, Mar 07 RT @OutfieldGrass24: Who's that under the radar player who you are banking on to break out this baseball season? Someone who's not regularly in the headlines?, Mar 06

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Who's that under the radar player who you are banking on to break out this baseball season? Someone who's not regularly in the headlines?, Mar 06 Just say "plague" already https://t.co/qkcwY2Omub, Mar 06

Just say "plague" already https://t.co/qkcwY2Omub, Mar 06 RT @wickterrell: You can certainly argue that he already has broken out, but I'm expecting massive things from Ramon Laureano this y… https://t.co/ejJPu9AEnd, Mar 06

RT @wickterrell: You can certainly argue that he already has broken out, but I'm expecting massive things from Ramon Laureano this y… https://t.co/ejJPu9AEnd, Mar 06

Powered by: Web Designers

[…] his success where so many others have failed is truly interesting. Not too long ago, we noted that Clippard’s splitter has been really, really good for the D-backs, and that Putz was the only other pitcher who had really thrown one in […]