Tyler Clippard Signing Means Higher 2016 Ceiling, Narrower Margin of Error

Early this morning, Nick Piecoro wrote at AZCentral.com that the D-backs and bullpen righty Tyler Clippard were making progress on a contract. This afternoon, Clippard and the D-backs ironed out a two-year pact that will pay Clippard a total of $12.25M. The D-backs had long been looking for a bullpen addition, and to that extent, this deal shouldn’t be a surprise. It certainly looks like a change in philosophy, however, and while Clippard looks like an upgrade if he pitches well, anything less than that kind of performance could encumber the team in a way even more significant than the financial commitment.

Assuming the $4M signing bonus component of the deal is counted evenly between the two seasons, Clippard will be paid $6.1M in 2016 — which would make him the third- or fourth-largest payroll commitment for the D-backs this season, depending on whether you count the $6.5M owed to the Brewers in the Chase Anderson trade. That’s a hefty bill for a team that hasn’t paid a reliever that much in a season in a long time, and yet Clippard could well be worth it.

The Upside: Tyler Clippard Has Been Really Good

According to the “Dollars” metric at FanGraphs, Clippard has been worth just about $6.5M per season, on average, since pitching his first full year in 2009. And that may actually be way too unkind to Clippard, because it is based on the FanGraphs version of WAR — which is as unkind to Clippard as it is to his polar opposite, a man they call Z.

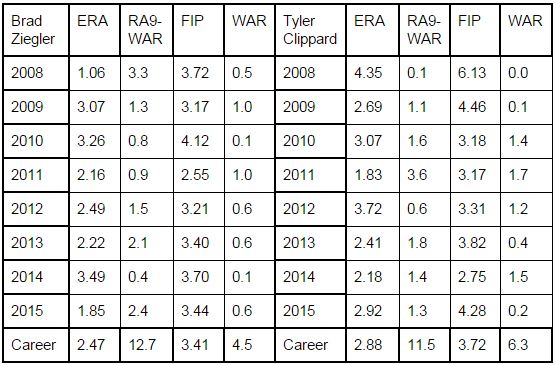

RA9-WAR is a lot like WAR, but it’s counted as if the pitcher can and should get full credit for all of his success — or lack thereof. Pitchers can be in friendly or unfriendly parks, can have great and terrible defenses behind them, and can be asked to face tougher hitters more often than the average pitcher. That’s the appeal of Fielding-Independent Pitching, and basing pitcher WAR on FIP — using strikeout, walk and home run rates, it guesses how well a pitcher should have done, based on those three things that pitchers appear to control all on their own. FIP is a quick-and-dirty way to see whether or not a pitcher has been lucky or unlucky, if you prefer to look at it that way, but what it seems to tell us about both Brad Ziegler and Tyler Clippard is that they’ve had a career’s worth of great luck.

Both pitchers have career ERAs that come dangerously close to one full run below their FIP — and the whole idea is that they should be roughly the same, especially over a very large sample of innings. The trick here is that Ziegler and Clippard are both completely strange in a way that makes FIP much less equipped to evaluate them than to the vast majority of their relief peers.

For Ziegler, it’s the insane ground ball rate that he’s sustained over his whole career, which has made him worth so, so much more than his other peripheral stats would indicate. Counting only strikeouts among outs gives Ziegler no credit at all for his propensity for double plays, for one; counting all balls in play as equal also gives Ziegler no credit for the high number of weak ground balls that are surer outs than the average ground ball. His true value in his career has probably been much closer to his 12.7 RA9-WAR than his 4.5 WAR for those reasons; we can point to them, and over 528.2 career innings, we can trust them.

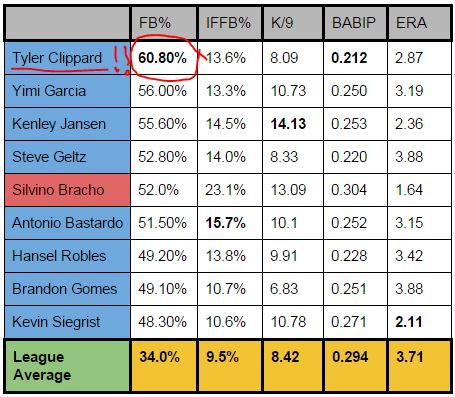

For Clippard, it’s the exact opposite. There are actually quite a few pitchers in most years who have ground ball percentages so high that they start to have BABIP-lowering tendencies, with fewer balls in play turning into hits than expected. The number of pitchers with fly ball percentages high enough to do a similar thing is an even more exclusive club; in October, it looked to me like once a pitcher’s fly ball percentage slipped below 47%, it stopped being helpful in terms of lowering BABIP. I was writing then, because it looked a lot like Silvino Bracho might be one such extreme fly ball pitcher. With Bracho moved to his proper place, I’m re-using a table from that piece here (again!), because recycling is a good habit, and because I don’t want you to think I’m moving numbers around just to make this Clippard story more compelling.

As of that writing, those were the top eight qualified relievers in fly ball percentage last year (plus Bracho), and no one came close to Clippard’s over-60% mark (he actually ended the year at 60.6%). Clippard had a huge dip in fly ball percentage in 2014, when he had a still-useful 49.4% FB% that still would have placed him on a similar leaderboard (7th) — and yet he’s dominated that category over his whole career (56.6%), also crossing that 60% threshold in 2008 and 2011. For reference, only seven qualified relievers have finished a season with a FB% over 55% in the last four seasons, and Clippard has three of those seven seasons. Bizarro Ziegler indeed.

Clippard’s batted ball profile goes a long way toward explaining his miniscule .232 career BABIP, all tallied without the cost of a high home run rate — his 1.04 career HR/9 is meaningfully above the 0.94 HR/9 that all relievers averaged last year, but not by much. With a fly ball percentage this high, Clippard reaps the rewards of high numbers of popups, and of better than expected success on fly balls (which tend to have higher launch angles than an average pitcher’s fly balls).

Clippard could also perform an important function in the D-backs bullpen, given that Andrew Chafin is currently the only lefty with a set spot, that Matt Reynolds would probably need to show something in spring training in order to earn a spot, that Keith Hessler set himself on fire toward the end of 2015, and that Will Locante was designated for assignment to make room on the 40-man for Clippard: he gets lefties out.

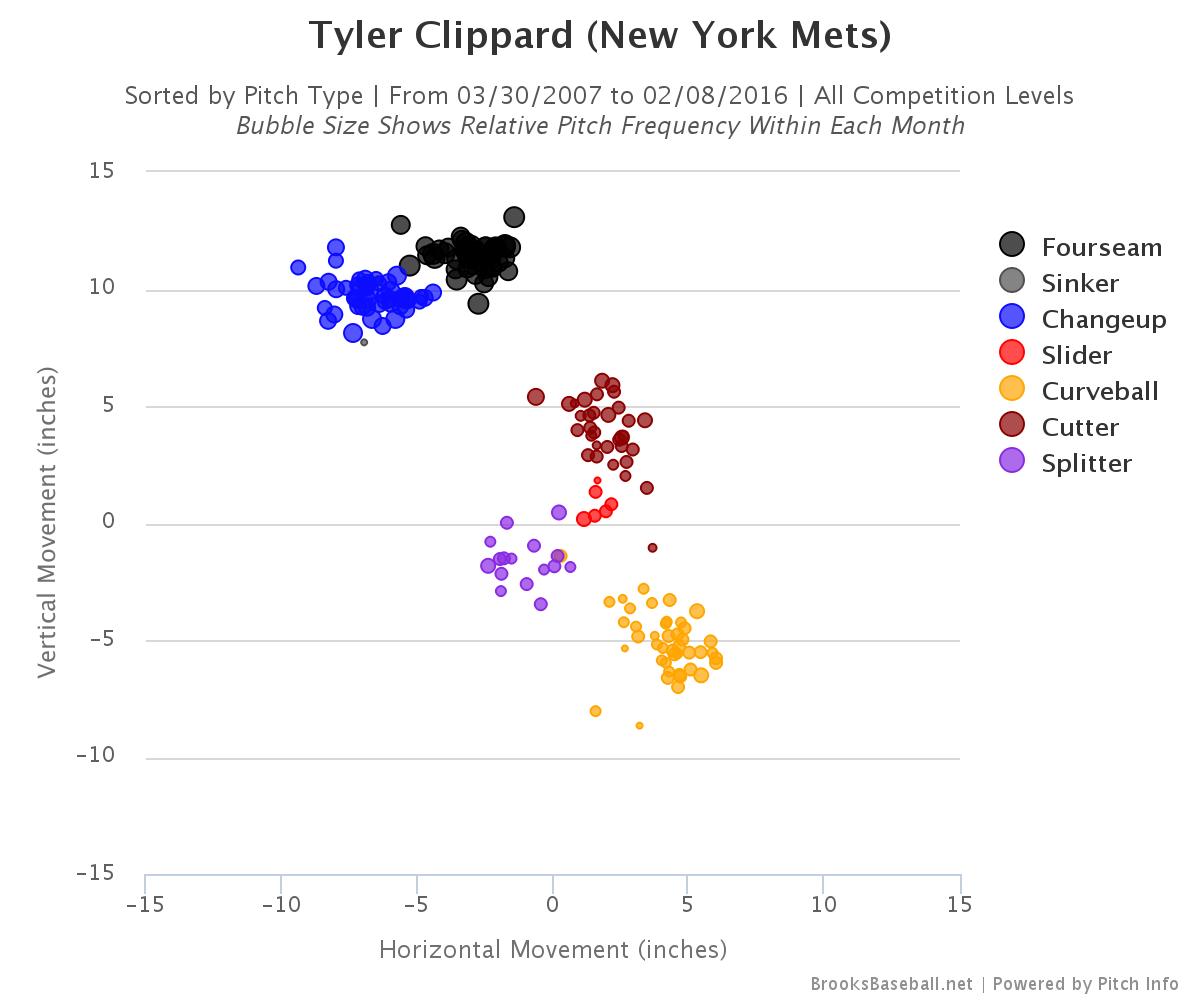

Over his career, Clippard has held lefties to a .179/.265/.307 slash line, a fair bit better than his still-excellent totals against RHH, .195/.287/.361. In 2015, the reverse platoon split was even more pronounced, .136/.231/.237 for LHH and .238/.333/.411 for RHH. Take a look at the movement chart above from Brooks Baseball. Remember when we found that the more horizontal a pitcher’s pitches were in movement, the bigger his platoon split? Clippard has tremendous vertical movement on his fastballs, over 10 inches on both of them in all but one season. That tremendous vertical movement and the lack of horizontal movement on his other pitches does more than go a long way toward explaining his fly ball rate: it comports with the idea that he’d have a reverse platoon split. Even if Clippard’s stuff were to wane, he could retain usefulness as a matchups man against left-handed hitters.

The Downside: It Could Be Bad

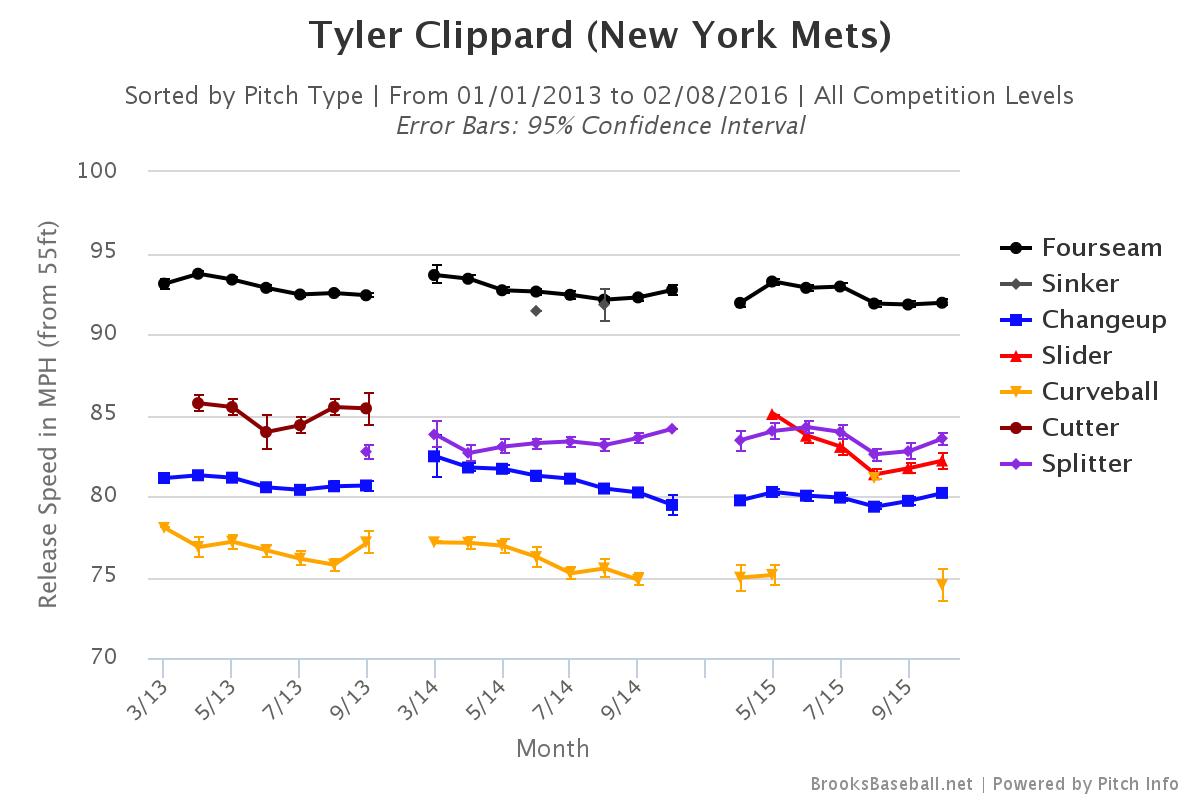

Two things should give us pause about using Clippard’s past success and how he achieved it to get confidence in his likely 2016 (and 2017) performance. One big one: his stuff has waned. Clippard’s first very good season was 2009, the first year in which his average fastball velocity climbed above 90 mph, by Brooks Baseball’s reckoning (release speed). It climbed after that, topping out at 93.6 mph on average in 2012 — and since then, it’s been in a very slow decline, descending each year to 92.4 mph last season, his lowest average velocity since 2009. Heavy usage may have taken a long-term toll on Clippard’s arm, but it also looks like it’s started to take a toll during the season: in each of the last three years, Clippard’s velocity has fallen off in August. Last year, that meant averaging just below 92 mph toward the end of the year.

Clippard had a rough time of it in September and October, so we can’t dismiss the velocity decline as trivial — and we’re looking to the future, when it’s unlikely that he’ll throw harder. Still, it’s the second thing that should give us the most pause, maybe: the fact that while Clippard is similar to Ziegler in consistently beating FIP with an extreme batted ball profile, it’s not like he’s doing it the same way.

Chase Field can be a tough place to pitch if you’re prone to fly balls; Addison Reed was right on that 47% cusp of helpfulness with his 47.6% FB% in 2014, a season in which ERA estimator SIERA liked Reed’s performance (2.68) a hell of a lot more than ERA (4.25) or FIP (4.03). That year, it was as if Reed was beating his FIP — but Chase Field beat him back, pushing his ERA back up above his FIP. By the way, Reed isn’t necessarily a poster child for Clippard’s likely success, if you’re remembering last year — as with just about everyone else, the D-backs changed Reed’s approach, spiking his GB% up (43.1% — is 34.0% for his career) and bringing his FB% well below that cusp of helpfulness (38.9% — now 43.7% for his career).

Or is he? Remembering Clippard’s profile from the Bracho studies, my first thought on hearing the D-backs interest in Clippard was whether they would change him. Surely, they can’t try to make MLB’s most fly ball prone pitcher a ground ball pitcher, right? Yet they did do so with Reed, who was not a much better fit for that model. At this point, “ground balls” seems to answer just about every pitching question. So why did they want Clippard? Let’s hope it’s not because they think he has been good despite his fly ball percentage, and that they can make him better by pitching down. Pitching up with a super-rising fastball is dangerous to hitters; pitching down with a super-rising fastball could be disastrous for Clippard.

Either a velocity drain or a failure for his fly ball rate to translate could torpedo Clippard’s effectiveness with the D-backs this season; the two can interact, as we have seen with Matt Cain when he’s pitched more recently. Trying to pitch down could be terrible for Clippard, but a lost tick or two of velocity could help keep the ball from traveling over opponents’ bats just enough.

The Worstside: If it’s Bad, it’s Really, Really Bad

A reliever’s shelf life is not usually very long in this sport; the best pitchers tend to be starters, and most pitchers fight Father Time from the moment they arrive in the big leagues. Some guys are just different; they became relievers not because they just wouldn’t be good as a starter, but because their profile translates especially well to the ‘pen, where they can stick to their two best pitches, or enjoy a meaningful and important spike in velocity going in shorter stints, or make hay with an unusual arm angle only seeing every hitter once per game.

The latter guys — the Craig Kimbrels of the world — are expensive. Very expensive. They also tend to be the most reliable of top relief performers. It all adds up to one thing: the very best possible bullpens might be the most expensive bullpens. Nothing too controversial there. The very worst possible bullpens might also be expensive, though, and that’s a lot less intuitive.

I took a tour through those thoughts over two years ago, when it seemed like a whole wave of relief prospects was hurriedly working its way to the big club. To wit:

Think about it, though: if a minor leaguer had struggled the way Bell struggled, he could get sent down and replaced with ease. He would get sent down and/or replaced. That’s the double curse of buying veteran bullpens — the inflexibility that comes with the significant payroll obligations.

Because the value of relievers tends to fluctuate so wildly, flexibility in that part of the roster is to be prized more there than it might be for an outfield crew or a starting rotation. Flexibility has a very real value in roster construction generally, but its value in the bullpen is significant…

…If money was absolutely no object and you could afford to keep signing expensive relievers (cutting the ones who struggled), then a bullpen made up of veterans has a much greater chance of being great than a bullpen composed mostly of young relievers. But a bad bullpen of young guys is a much better situation than a bad bullpen of veterans. A bad bullpen of veterans with salaries too big to waive is the worst case scenario.

This preference for a young bullpen is independent of the fact that veteran bullpens are more expensive. The preference is solely about flexibility.

Every major league player who is not a reliever has a chance to fix something that’s broken, whether it’s by more work in the cage or working on something in a side session. Relievers can’t do side sessions, though; they’ve just thrown, or they need to stay available. It’s a hard reality. What if David Hernandez struggled through the 2013 season unnecessarily, and the adjustment and bounce back he made in the minors toward the end of the year was something that could have been done sooner? What if he was out of major league options, and couldn’t be sent down for that purpose?

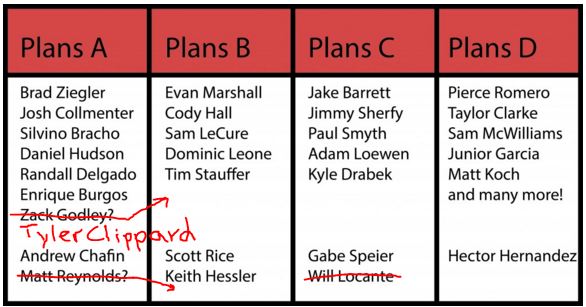

The D-backs bullpen is stacked or close to it this year, and what they lack in quality they make up for in quantity. Fronting the bullpen, however, are five pitchers who can’t be optioned in Brad Ziegler, Tyler Clippard, Daniel Hudson, Randall Delgado and Josh Collmenter (as best as I can tell; Hudson’s situation is especially funky, and I’m not sure on Collmenter). Andrew Chafin can be optioned, but was one of the team’s best two relievers last year. Chafin is also projected to be the team’s second-best reliever in 2016 — behind Silvino Bracho, who can also be optioned. That’s it; that’s your top seven pitchers — the team might go with eight relievers for much or most of the year, but replacing one of those seven pitchers is only likely to be an upgrade if one of them is on the disabled list.

Matt Reynolds, Scott Rice, Tim Stauffer, Cody Hall, Kyle Drabek, Evan Marshall, Enrique Burgos… they’re all just minor league depth now. Some “Plans B” or “Plans C” pitchers on minor league deals like Sam LeCure and Adam Loewen can be kept in the minors to start the year, but if they are called up, they clog the mechanism even more — they can’t be sent back down without their permission.

One of the ways to best use a quantity-over-quality organization of relievers might be to switch guys in and out, depending on success and depending even more on whether or not a pitcher could likely benefit from some time to work out the kinks on something. Rearranging the deck chairs can be helpful — and having more and more pitchers who can’t be moved out temporarily is like bolting more and more of those pitchers to the floor.

What this comes back to is the two-year nature of Clippard’s deal. If he’s struggling mightily in April and May, what can and should the team do? There would be every reason to think Clippard could be an asset at some point in 2016, and confidence that he would be more helpful than a replacement in 2017, too. They’ll have to try to have him work it out on the fly (well, if they let him work batted balls on the fly), and hope for the best, which is often the right call with good relievers anyway. What about July, though, if the D-backs are in the thick of it and it’s just not working out too well with Clippard? The trade of Aaron Hill sure made it look like the D-backs are more reluctant than most to cut bait.

Saying this whole point differently: the downside with a young reliever is what we saw with Evan Marshall in 2015, who put up a staggering -0.4 WAR in 13.1 innings before getting sent down. You can’t stop the bullpen from bleeding that way, but you can stop the bleeding. What if Evan Marshall couldn’t be optioned? Consider how excellent his 2014 season was. The downside with a veteran reliever can be a whole lot worse, because you can’t stop any reliever from struggling, but veterans are the only pitchers you have to either use or lose.

On the whole, the Tyler Clippard signing is a good use of funds, and he does make the 2016 bullpen better on and off paper. Be happy; the team is in a better position to win a maximum number of games in 2016, and Plan A is a better plan. The number of bullpen spots that could go to optionable relievers, however, did just get smaller by a significant stretch, down from three to two. Plan A is better — it’s just a fair bit less flexible.

12 Responses to Tyler Clippard Signing Means Higher 2016 Ceiling, Narrower Margin of Error

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Biggest takeaway from watching https://t.co/V9skCPImzi again: I apparently need Blue Emu in a bad way, 17 hours ago

Biggest takeaway from watching https://t.co/V9skCPImzi again: I apparently need Blue Emu in a bad way, 17 hours ago A full heart on a beautiful almost-anniversary Saturday ❤️😍😍❤️ @ Timothy Lake https://t.co/w3neRm4xUl, Jul 19

A full heart on a beautiful almost-anniversary Saturday ❤️😍😍❤️ @ Timothy Lake https://t.co/w3neRm4xUl, Jul 19 Brief friend alert https://t.co/JEUdHvJmPT, Jul 17

Brief friend alert https://t.co/JEUdHvJmPT, Jul 17 My family donates every month. It's a priority. Please consider donating with us. https://t.co/ksvDBZim4S, Jul 17

My family donates every month. It's a priority. Please consider donating with us. https://t.co/ksvDBZim4S, Jul 17 RT @ClueHeywood: @Garrett_Archer Numbers have a well known liberal bias, Jul 17

RT @ClueHeywood: @Garrett_Archer Numbers have a well known liberal bias, Jul 17

Powered by: Web Designers

This is great–thank you, as usual, for the great content. Coupla things.

1. Are you as convinced now as before that this FO is implementing a Grand Ground Ball Strategy? I admit that I’ve never been convinced that they are, mostly because I’ve never read anything like that from *them*, but in part too because I just don’t think this is a Grand Strategy kind of FO. Anyway, as you rightly note this signing doesn’t fit such a strategy too well if it does exist.

2. Too bad they couldn’t, or didn’t, make the Hill trade earlier in the offseason so that they had more choice among relievers.

3. The Hill trade now looks significantly better if we look at Clippard as part of the return. I’m actually OK with it now.

4. I didn’t realize Clippard was death on lefties. That’s a great bonus. Obviates the need to carry Reynolds or Wright.

5. I’m not sure the downside here is quite as bad as you make out. If Clippard really falls apart in 2016, he goes on the DL for a while, perhaps a good long while, and tries to figure it out in the minors on rehab assignment. Call it the Trevor Cahill plan. Pretty easy to do. And while the money is considerable for a reliever, it’s not really a handcuffing amount either this year (there should still be money in the budget for adding salary in-season if necessary) or next. The risk just isn’t all that high.

I think this is a good signing. Not perfect. Not a Grand Strategy signing. But a good one.

Thanks, Lamar, and great comments, as always.

1. Yes, definitely. It’s not that they’re only prizing ground ball pitchers, but mostly that they’re trying to accumulate them. I think they learned their lesson that fly ball leaning pitchers should be left alone — Collmenter was the same guy he once was after being returned to the bullpen. Where they can make something out of nothing using ground balls (Godley), they will; if they can find minor league free agents along those lines, they will; and most of the pitchers will be mostly down this year, once again. I imagine they will leave Greinke alone, though.

Clippard gives the team the best possible case to NOT try to remake a pitcher, so if they leave him alone, I wouldn’t read too much into it. Still surprising that he was their guy, but it was a week into February, and more than most, this front office seems to value ERA for what it is: actual results (see: Shelby Miller). That’s not a bad thing, especially when there’s a reason to believe.

2. Yeah, probably. But it’s not like this payroll money gets paid year round… they could have stretched if they thought it was important. I’m not sure they were waiting for Hill salary relief; it might be more that they were trying to exhaust all avenues to add a reliever via trade. I’m guessing a trade of Chase Anderson was desired by the D-backs, and if they were exploring reliever trades with their starter depth, that might explain the delay more. In other words, I completely agree with your point.

3. One of the first things I thought to myself was: “would it be a good idea to trade Isan Diaz for two years of Clippard at $12.25M?” That does seem pretty reasonable. But it’s probably not that healthy to change the look of the trade that way; true or not, the fiction is that the D-backs paid Clippard more than other team wanted to pay him. It looks like a pretty good deal, but free agent pacts rarely have positive value right after they’re signed.

(note: we don’t actually know that for sure, especially since newly-signed free agents can’t be traded right away, as a practical matter. But as much as we might like the Greinke deal, does he have a positive trade value right now?)

4. Yeah, neither did I. Love it. And unlike with Perez, where the sometimes-reverse split might have been caused by only facing weak RHH, we have reason to think Clippard will keep this. If Chafin were more of a matchups guy, Clippard would be a great fit for the role that Chafin actually had last year. The team might still want a matchups man, though, and may not want to use Clippard in that role, either because they don’t trust the reverse split (which would still be reasonable), or because they want to get more innings out of him than that. After all, he was in more of a Collmenter role for a long time with the Nats, and was extremely effective getting deployed that way.

5. Yeah, I think you got me there — I should have included some of these counterpoints. I probably did overstate my case. If “arm fatigue” is a valid reason to put a pitcher on the DL, it’s justification enough for EVERY pitcher to be put on the DL. Not every “fix” is as quick as Hernandez’s was in 2013, though, probably — Marshall never really got it back in 2015. There are limits to the length of rehab assignments under the Collective Bargaining Agreement, and the main point in the piece above along those lines — that options/lack of options can force a team to pick between its best possible bullpen or not losing every potentially valuable reliever — probably still stands.

On Cahill, I think you’re referring to 2013? I agree, that’s the kind of thing we’re looking at (but maybe they still don’t pull that trigger as fast as, say, sending down Burgos last year). Cahill’s 2014 is more in line with the “worstside” I meant. To move Cahill to the minors, they had to designate him for assignment, which exposed him to waivers when they outrighted him. In other words, before moving him to the minors became safe, they had to let him stink up the joint for a while first. With optionable relievers, there may never be that good a reason to stick with a below-replacement-performing pitcher for longer than they did with Marshall in 2015.

I think this is a good signing, too, and I think I feel the same way: not 10 out of 10, but a clear positive. Might not be a move in the “ALL THE GROUND BALL PITCHERS” Grand Strategy, but squarely within the “2016-2017 AT ALL COSTS” Grand Strategy.

Sorry for the length — I love this stuff. Thanks for the comments!

I love this stuff too! Appreciate the engagement and the conversation.

With reverse splits Clippard on board and Rice, Wright and Hessler as depth left handers, would you now trade Reynolds?

Similarly, with Godley now a depth piece, along with Stauffer, would you now trade Delgado?

If anything of value could be had for Reynolds, then yes, in a heartbeat. Rice could end up being the guy, anyway, and Hessler in particular is a completely adequate backup plan.

On Delgado… I don’t think so. Godley is cheaper, but Delgado is still very cheap. Above average innings (or even average innings) are worth quite a bit. I’d rather see Collmenter moved into a short relief role, I think, with Delgado the long man.

A lot of Godley’s value right now, IMHO, is that he has option years remaining. Someone can always be moved into long relief, as needed — not everyone can be moved in and out of the rotation in a spot start role. I think Godley is the lead candidate there, with Bradley more of a lasting solution if a pitcher were to be out for a while. Jostling Bradley around with extra or fewer days of rest seems scary. Godley is the guy I’d want answering that bell.

Stauffer may start the year in the minors, but from what I understand, once he’s up and added to the 40 man, the D-backs would need to designate him for assignment to move him back down (and get Stauffer’s permission).

Agree on both, but…since Delgado has so much value, including the possibility that he could still work into a starting rotation, do you think the D’backs need for a fourth outfielder or a backup catcher would justify trading Delgado if a quality option at either of those positions presented itself? Understanding that Godley and others could adequately backfill Delgado’s role in the bullpen.

Baseball people used to say that diversity in pitching was a good thing. You wanted “different looks” especially coming out of the bullpen. Under that concept Clippard is a great fit for the D’backs bullpen. I haven’t seen any sabermetric analysis of that concept, but maybe Zeigler’s uniqueness is an example. If so, the opposite extremeness of Clippard’s fly ball rate success may be another good example?

I completely believe that — different looks is a great thing. We know there’s a significant Times Through the Order Penalty for pitchers, and it stands to reason that the more different the pitchers are, the more that could work in reverse. The only thing I’ve seen like that is on what it seems to do to hitters to have seen R.A. Dickey the day before — 1.4 wins of value is huge. http://www.fangraphs.com/community/the-r-a-dickey-effect-2013-edition/

It is probably a two-way street. Brad Ziegler probably benefits from the hitters he sees having just worked against someone more conventional — AND a pitcher might derive a benefit after Ziegler, if the hitter has just faced Ziegler. The batting order is hard to manipulate, but it seems to me a formula of Starter, then Some Unconventional Guys, then Closer (who can be conventional if the previous guys have not been) would make great use of that different looks effect, if any.

Add Clippard to the mix. Good luck facing Z after facing him, or Chafin (hahahaha). Maybe you want to avoid hitters going straight Good luck facing Clippard after facing Bradley.

Maybe you’d want to keep him away from Collmenter (or pitch them back to back, if together they don’t repeat anyone in the order), but if you’re trying to mix it up, Clippard is a great guy for that. Bracho looks like another elite fly ball guy, but he does it with a completely different approach (which yields strikeouts), and with a wide enough velocity gap between them for that to be jarring, too. With so many ground ball types on the team, Clippard would fit many more situations than anyone not as extreme with ground balls as Ziegler. Pretty solid argument here, for example, that Clippard could be a better fit than Darren O’Day.

I have no idea whether very different is better than just different enough. But I think you’re right: different is great.

Perhaps an unusual idea: Like with left and right handed hitters, can the Dbacks “platoon” Ziegler and Clippard based on the batted ball tendencies of the hitters coming up? I know the fly ball hitter and ground ball hitter profiles were smaller effects than handedness, but we’re talking about the two most extreme pitchers in the game in this respect, and probably not something opposing managers are going to take into account when constructing their lineup (typically with a top of the order hitting more ground balls to get on base and a middle of the order hitting more fly balls to get more power).

[…] newest Diamondback is another victim of the methodology here. As Ryan profiled yesterday, Clippard has been very productive over the years, but he’s so opposite of Brad Ziegler that it’s bizarre. Clippard is an extreme fly […]

[…] Analysis […]

[…] Tyler Clippard is just as fascinating, however — and while he could be fairly described as “Bizarro Ziegler,” there’s reason to think Clippard’s brand of success may be just as […]