Josh Collmenter’s Fall and Rise

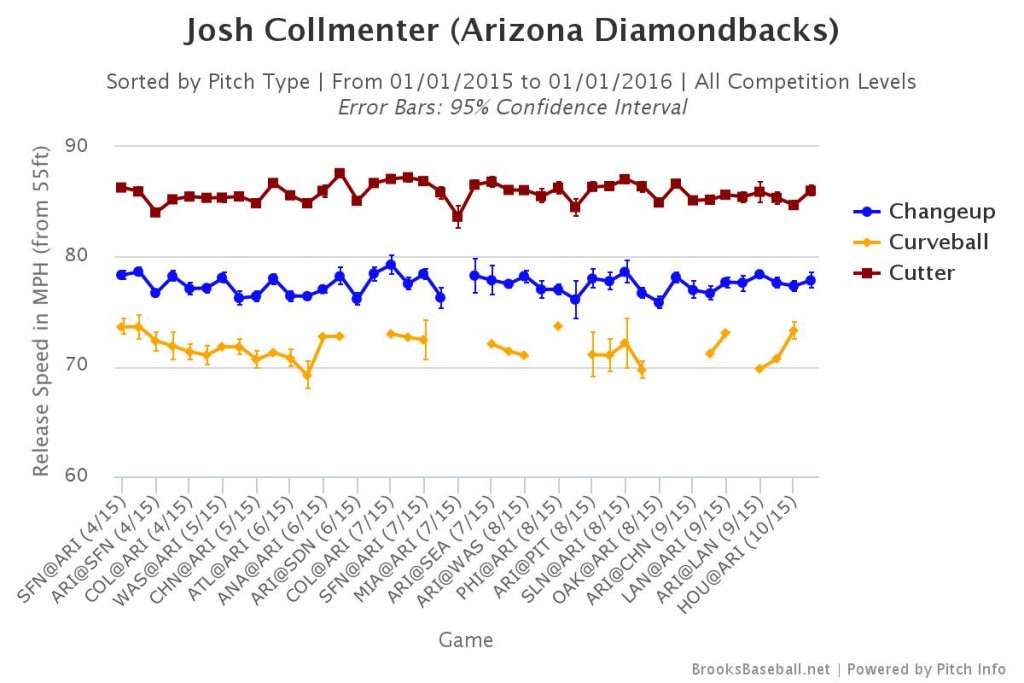

Why is Josh Collmenter so good? I’m not saying that because he was the starter on Opening Day, and I’m obviously not saying that because of his 5.24 ERA this season as a starter. The man still pitched a near-full-season’s worth of relief innings (52.1), and once again, the results were spectacular: a 1.89 ERA.

What Collmenter has been able to do borders on the bizarre, and not just because he throws up his arm as often as the annoying kid in elementary school. In relief this season, batters hit just .228 off of Collmenter. Fluke? Try again. As a reliever, the man has thrown over 200 career innings, with a career batting average against of .229. He’s done it with a set of tools only slightly better than my first one, that sent me to the emergency room one regrettable Christmas. It really shouldn’t work. And when Collmenter has started, it kind of doesn’t. Why is he so good in relief?

The Tools

Four-seam fastballs seem so passé in this age of sinkers and cutters, and Collmenter hasn’t bothered with one since well before his MLB debut. Brian Bannister tried the same thing at the end of his career, and he’s said he thought it was really working — his career ended due to shoulder woes, and not because he was wrong (congrats to Banny on the new gig!). Collmenter offers some support for that idea.

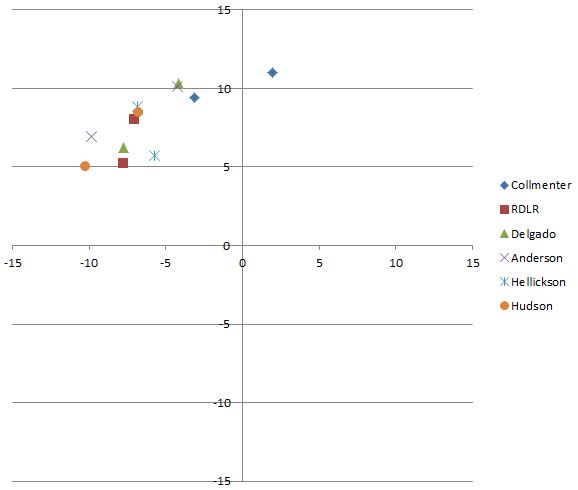

There aren’t many guys who survive with a not-particularly-high 80s fastball; the newly-available Statcast numbers have Collmenter’s cutter at 85.48 mph on average, and even among cut fastballs that’s low (MLB average is 88.05 mph). His is also fairly unique: of the 58 pitchers to have thrown at least 200 cutters this year, Collmenter has more “rise” on the pitch than any of the rest. His 11.01 inches of vertical movement beats the average for #2 Aaron Harang (10.18) handily, and Collmenter is one of just four pitchers with as much as 8 inches of “rise” on average.

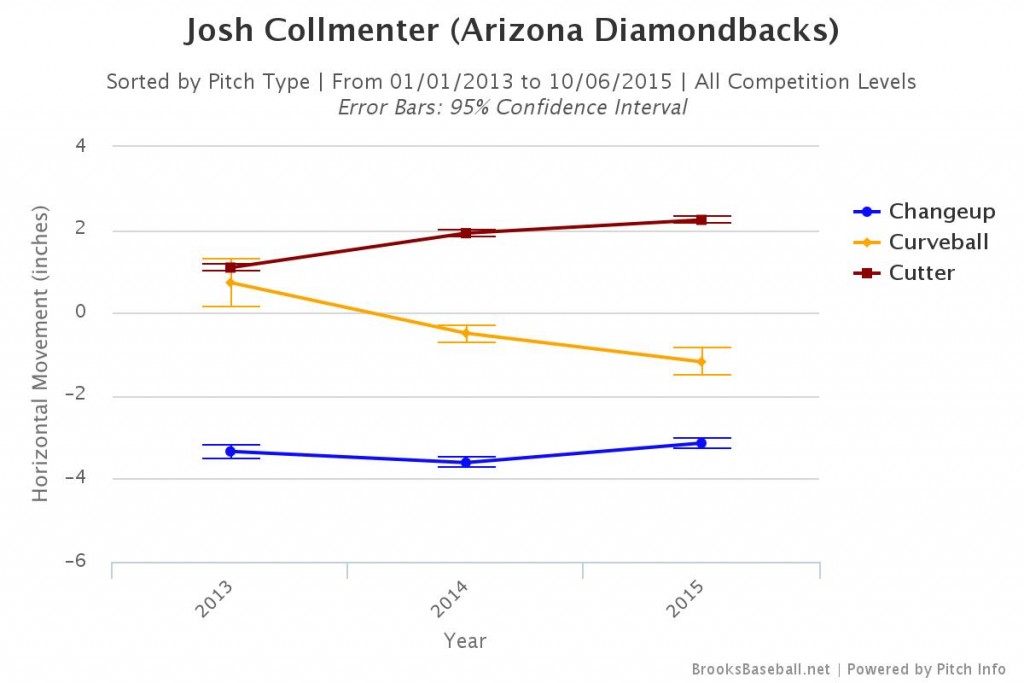

In other words, Collmenter’s cut fastball looks exactly like a normal fastball, in every way but one: it breaks in the wrong direction. It’s normal for a fastball to break to a pitcher’s arm side, and so looking at horizontal break for a cutter is misleading: it never looks like much, but the point is what that it’s not not breaking the other way. It’s usually the case that a pitcher’s four-seam fastball and changeup have almost identical horizontal break. So you can see what I mean in how the pitches stack up:

A four-seam from a right-hander should have a negative number; and so it’s probably fair to say that Collmenter’s cutter “cuts” by about 4 or 5 inches, not by 2. Let me try again. This is a scatter plot of the average movement of some D-backs right-handers’ fastballs and changeups this season, with the center of the graph being a theoretical spinless pitch. You can guess which ones are the changeups because they don’t “rise” as much.

See what I mean? In terms of movement, it’s actually Collmenter’s change that looks more like a four-seam fastball. But as you can see from the two-pitch combinations of Rubby De La Rosa and Jeremy Hellickson in particular, it’s also fairly normal for the two pitches to have similar horizontal movement.

I have no idea what it’s like to try to hit at the MLB level, but that does look difficult. And the results speak for themselves: over his career as a reliever, the Pitch Values at FanGraphs have Collmenter’s cutter solidly above average among all fastballs, at nearly one run above average per 100 thrown. His changeup rates even better compared to other changeups; 0.96 Pitch Value/100 for the fastball, 1.22 for the change. Maybe you wouldn’t call them “plus,” but two above average pitches can get you a pretty long way.

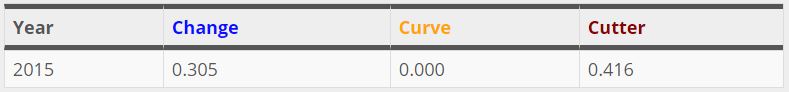

The curveball is… not in the same category. The same Pitch Value/100 number for the curve is -3.26, or roughly three runs worse per 100 thrown. Randall Delgado‘s curve has been worse, but the next-worst pitches thrown a meaningful amount this year by any D-backs pitcher are RDLR’s change (-1.85 PV/100) and Robbie Ray‘s slurge (-1.19 PV/100).

On an episode of the lovely D-backs Podcast this offseason, Collmenter described the curve as key to sticking in the rotation (I’m paraphrasing). In the end, it was his ticket out of the rotation: even though he threw it very infrequently, Collmenter’s opponents slugged .800 off of the curve this season, compared to .500 on the cutter and .392 on the change. It’s hard to evaluate a pitching coach, but the failure of both Collmenter and Ray to learn a usable breaking ball in the spring and during the season is not exactly a feather in Mike Harkey‘s cap.

Starter vs. Reliever

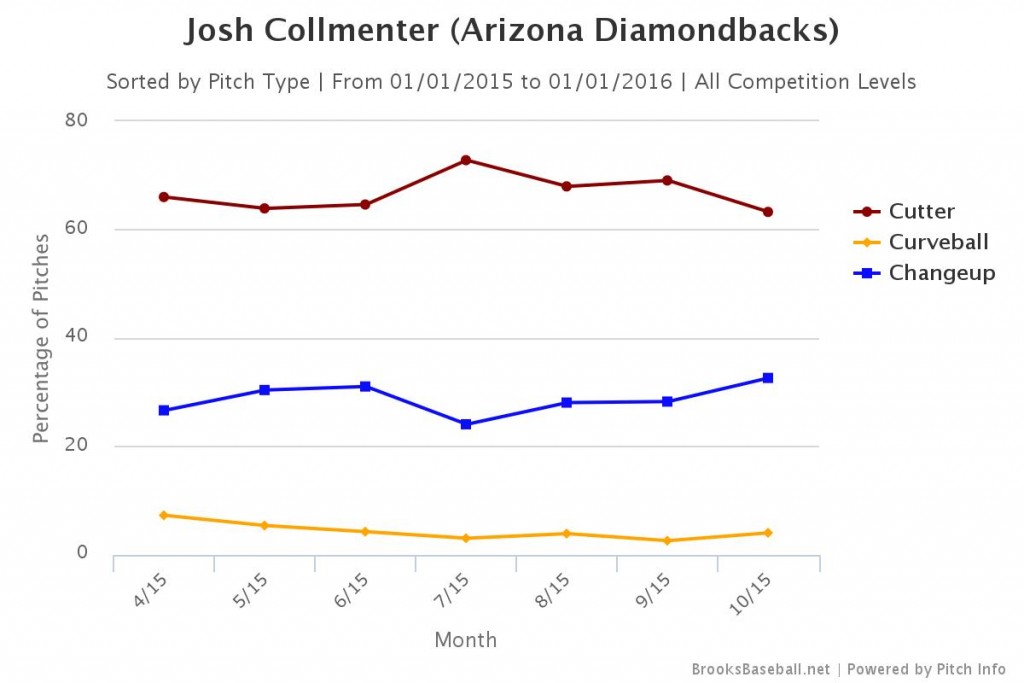

When things really went downhill for Collmenter in May, I thought there was pretty good evidence to suggest that a decline in velocity was to blame for his struggles; maybe when you get slower than fairly slow, it starts to catch up with you — although, as noted in that same piece, evidence suggests a decline in velocity does matter less when you’re already starting on the low end (about 0.10 of ERA per 1 mph, instead of the average of 0.24 of ERA per 1 mph). That may be true. Collmenter made his first relief appearance this season on June 18, and while his average cutter velocity in the season’s first three months were just 85.27, 85.62 and 85.46 mph; in July it was 86.71 mph, one magic mile an hour better. Still, check out his game-to-game velocities:

This isn’t an “oh man, he really leapt up once he was in the bullpen” phenomenon like we’ve seen with Daniel Hudson. It’s all vaguely the same. Instead, it could be the lack of a usable third pitch that really bit Collmenter.

At the outset of 2014, I wrote that Collmenter might be especially susceptible to the “Times Through the Order Penalty,” or “TTOP.” Other researchers have found that the TTOP has been more or less the same for everyone; there aren’t pitchers who avoid it more or less. Part of that may be the great competition engine that is baseball, with teams making fairly accurate evaluations of who pitchers are because they have a strong incentive to do so; at any rate it doesn’t look like some pitchers are “better” at going deep into games, just better at pitching overall.

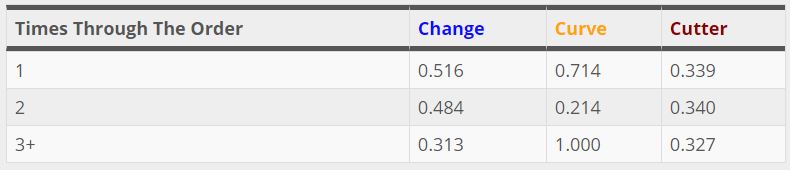

The D-backs promptly put Collmenter in the rotation anyway, and the rest of the season made me look pretty stupid. Other than a loud alarm that Collmenter not show his infrequently-thrown curveball to anyone twice, he was pretty flat across the board in 2014:

As the game wore on, Collmenter threw his cutter less and less (from 77% down to 63%) and his change more and more (17% to 29%). It seemed to be working. This year, Collmenter used a similar approach, but the results were… not great. This was the slugging percentage against each of his pitches this year, while he was in the rotation:

He definitely did worse the third time through than the second time (he only threw 26 curves the second time through the order, so let’s not go crazy about that). But Collmenter was also pretty awful the first time through. That probably sounds familiar to you, because it sounds familiar to me: Collmenter had trouble deep in games when he got there, but it seemed like he got completely ambushed a few times, too.

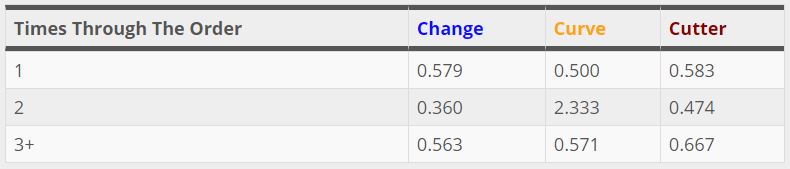

I can only speculate now, but I think “the book” is Collmenter’s first and worst enemy. He’s weird; but maybe he’s not so weird that you can’t prepare to face him. Everyone has seen him now, and what’s left might be the reverse of the “After Dickey” effect. Start out the game against him, and he’s not so bad. But if you just saw a “normal” pitcher your last time up, Collmenter is hard to keep up with. His slugging percentages against as a reliever this season:

Pretty great. Against Collmenter’s change, opponents slugged like Chris Owings did this year. Against his cutter, they did only slightly better: like Ender Inciarte. And could things really be as simple as that curve? Seeing Collmenter usually just once, hitters had enough to do to simultaneously figure out that the cutter wouldn’t do what a fastball normally would, and that the change would still “rise” like a fastball. Maybe in that context, a curveball 7% of the time just does not compute for hitters, but they can crack the code easily and well when Collmenter starts.

More exposure is definitely not Collmenter’s friend, although I’ll reiterate what I wrote at the beginning of 2014, that he could still be used more and probably not run into a big issue. In relief, though, all we’ve seen from Collmenter is something akin to domination. Brad Ziegler is a non-traditional closer, and there’s a good if unconventional case to put Daniel Hudson in the same role. Just like Ziegler may be needed in a different role, Collmenter is extraordinarily valuable in long relief — and yet when tapped to provide those innings, the game is frequently out of hand. Could Collmenter be an effective closer? I wouldn’t bet against him.

3 Responses to Josh Collmenter’s Fall and Rise

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

#Dbacks' 2018 1st round pick Matt McLain hit .203/.276/.355 as a freshman at UCLA last year. This season? A tidy li… https://t.co/yM48j1ebrr, Mar 07

#Dbacks' 2018 1st round pick Matt McLain hit .203/.276/.355 as a freshman at UCLA last year. This season? A tidy li… https://t.co/yM48j1ebrr, Mar 07 RT @OutfieldGrass24: Who's that under the radar player who you are banking on to break out this baseball season? Someone who's not regularly in the headlines?, Mar 06

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Who's that under the radar player who you are banking on to break out this baseball season? Someone who's not regularly in the headlines?, Mar 06 Just say "plague" already https://t.co/qkcwY2Omub, Mar 06

Just say "plague" already https://t.co/qkcwY2Omub, Mar 06 RT @wickterrell: You can certainly argue that he already has broken out, but I'm expecting massive things from Ramon Laureano this y… https://t.co/ejJPu9AEnd, Mar 06

RT @wickterrell: You can certainly argue that he already has broken out, but I'm expecting massive things from Ramon Laureano this y… https://t.co/ejJPu9AEnd, Mar 06

Powered by: Web Designers

Josh would od survived and thrived as a starter too. But thats an arguement for a different day.

Maybe, maybe not. But both times the team tried him as a starter he had initial success then failed miserably. This leads me to think he wouldn’t be successful long term, or at least he would be inconsistent. Meanwhile he has been wildly successful as a reliever, leading me to believe he’s probably more valuable as a long reliever.

For a team with very little depth in their starting rotation he would be needed as a starter. However, the Dbacks as we know have a ton of depth in the mediocre starters with potential category. I’d rather give the rotation spot to a Aaron Blair, Archie Bradley, Chase Anderson, Jhoulys Chacin, or even a Rubby De La Rosa.

[…] Wednesday when looking at Josh Collmenter‘s return to greatness, I referenced a point about how declining velocity has a lower ERA “price” for pitchers […]