Fastballs and Changeups and Diamondbacks

Strikeouts were a problem for the Diamondbacks’ pitching staff in 2015. As a collective group of pitchers, they were 19th in the majors in strikeout rate. The starters were 18th and the relief corps ranked 24th. It was a bottom-third result when you put it all together in terms of strikeouts. We like strikeouts, but as you’ve hopefully noticed here, ground balls are good, too. If you can’t get a ton of K’s, ground balls are the next best alternative. In that respect, the D-backs finished a much more palatable 13th in the majors, thanks in large part to a unusually ground ball-prone bullpen. That’s more like it.

The increase in ground balls has largely been attributed to more sinkers from Diamondbacks pitchers, but as Ryan proved to us in the waning moments of 2015, sinkers aren’t for everybody. As he showed, thanks in large part to the strong research by Max Marchi, vertical fastball movement has far more to do with successful fastballs than purely “fastball type.” Essentially, it matters what the pitch does, not which exact type of fastball a pitcher throws. Four-seamer, two-seamer, sinker, cutter or any other fastball – what the ball does out of the pitcher’s hand from a vertical standpoint will largely determine its overall effectiveness. Of course, velocity, command, control, mechanics, arm slot and overall repertoire will factor in, but it looks like we, as a baseball community, have been overlooking the importance of vertical fastball movement.

The work of friend Jeff Long at Baseball Prospectus last week pushed me in a new direction. In working with Harry Pavlidis on what makes a good changeup, Jeff pointed out the following major principles:

- A large gap between fastball velocity and changeup velocity results in more whiffs on the changeup

- A smaller gap between fastball velocity and changeup velocity results in more grounders on the changeup

- The wider the gap between vertical fastball movement and vertical changeup movement, the more grounders and whiffs the changeup will generate

I feel like we’ve been pretty conscious of principle number one for quite some time. We’ve come to expect that a pitcher should, optimally, throw his changeup eight to ten miles per hour slower than his fastball. Principle number two makes sense, but I don’t know that we’ve ever really stated it outright. Maybe I’ve come across it somewhere at some time, but I think it’s a useful observation that is closely related to principle number one.

The third major principle is something I’d never previously pondered. Maybe it’s due to the fetishization of velocity – we look to velocity to explain far more than it’s capable of. The importance of vertical movement of fastballs was clearly established by Marchi, and more recently by Ryan, but how that movement relates to a pitcher’s changeup is apparently quite important, at least in so far as creating an effective changeup. If the gap between vertical fastball movement and vertical changeup movement creates quality changeups, that’s something we’d surely want to identify for Diamondbacks pitchers.

But first, we have to evaluate the field and establish some kind of baseline. I looked at all pitchers in 2015 who threw at least 30 big league innings. Of those, I only considered pitchers who threw their changeup at least 8% of the time, then filtered the remaining pitchers by fastball type. As you’re aware, there are multiple fastball classifications. I chose to look at the three most prevalent according to PITCHf/x – four-seam, two-seam and sinking fastballs. I defined each group based on which type of fastball they threw most often, and the prevailing fastball had to be thrown at least 10% more often than any other type of fastball. Some pitchers mixed, for example, four-seam and sinking fastballs almost equally. Because there was no prevalence for which to compare the changeup, I withheld these 31 pitchers from the study. This left me with 158 pitchers to analyze. On to the results.

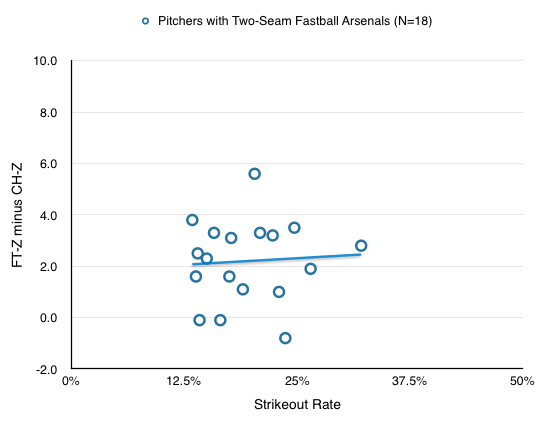

Pitchers with Four-Seam Repertoires

These pitchers all threw their four-seam fastball at least 10% more often than any other fastball type. The group averaged 49% four-seamers and 16.5% changeups, resulting in an average strikeout rate of 20.4%. The average four-seam fastball had 9.4 inches of vertical movement while the average changeup had 5 inches of vertical movement, creating a 4.4-inch gap. Plotted on a chart, here’s the relationship between strikeout rate and vertical fastball/changeup gap:

There is clearly a relationship between vertical fastball/changeup differential and strikeout rate. As that gap widens, the strikeout rate appears to increase accordingly.

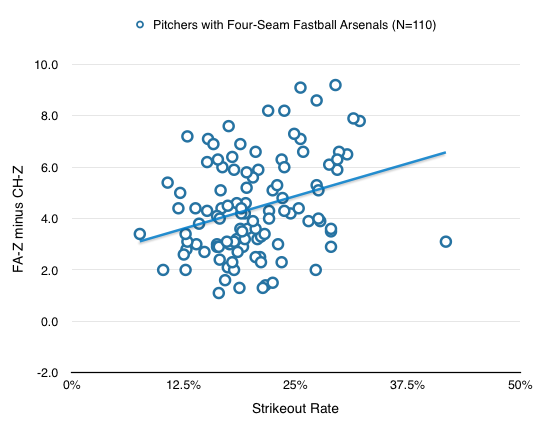

Pitchers with Two-Seam Repertoires

These pitchers all threw their two-seam fastball at least 10% more often than any other fastball type. The group averaged 49.2% two-seamers and 18.5% changeups, resulting in an average strikeout rate of 19.5%. The average two-seam fastball had 5.7 inches of vertical movement while the average changeup had 3.5 inches of vertical movement, creating a 2.2-inch gap. Plotted on a chart, here’s the relationship between strikeout rate and vertical fastball/changeup gap:

While this is a much smaller group, there’s very little, if any, relationship between vertical fastball/changeup differential and strikeout rate. Given the lack of “rise” on the two-seamer, the extra “sink” of these changeups hardly matters as it all adds up to smaller vertical differences and fewer strikeouts.

While this is a much smaller group, there’s very little, if any, relationship between vertical fastball/changeup differential and strikeout rate. Given the lack of “rise” on the two-seamer, the extra “sink” of these changeups hardly matters as it all adds up to smaller vertical differences and fewer strikeouts.

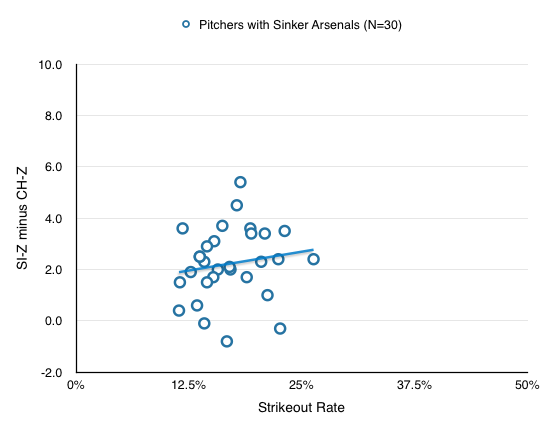

Pitchers with Sinker Repertoires

These pitchers all threw their sinking fastball at least 10% more often than any other fastball type. The group averaged 48.9% sinkerss and 17.3% changeups, resulting in an average strikeout rate of 17%. The average sinking fastball had 5 inches of vertical movement while the average changeup had 2.7 inches of vertical movement, creating a 2.3-inch gap. Plotted on a chart, here’s the relationship between strikeout rate and vertical fastball/changeup gap:

The relationship here between vertical fastball/changeup differential and strikeout rate is more observable than the group above, but barely so. We know that there isn’t much separating two-seamers and sinkers. The relationship between each of these two fastball types and their corresponding changeups shows near-parallel results.

A Formal Observation

If the gap between vertical fastball movement and vertical changeup movement is as important as Jeff Long and Harry Pavlidis have observed, it would be intuitive that the changeup would play best off of four-seam fastballs. Four-seamers have the most vertical “rise,” helping strongly separate it from the “sink” of a changeup. Naturally, this is going to create a bigger gap than that which exists between fastballs with less rise (two-seamers and sinkers) and changeups. Additionally, we get the added benefit of higher average velocity among four-seamers than any other fastball type, helping create the biggest velocity gap between any type of fastball and changeups.

Put it all together and we get the biggest vertical movement and velocity gaps between four-seam fastballs and changeups as compared to any other fastball type. This doesn’t mean that two-seamers and sinkers shouldn’t be paired with changeups. Chris Sale (two-seamers) and Felix Hernandez (sinkers) are living proof that you can have a dynamite changeup while throwing a fastball other than a four-seamer most often, but they’re also clearly outliers. For the rest, it appears that this relationship is important in terms of generating strikeouts with the changeup. Sure, the changeup is just one pitch, but it can be deadly when used properly.

Changes in the Desert

It has long been known that in dry air, especially at altitude, breaking balls don’t break as much. There’s less resistance from the atmosphere for the seams to grip. This is why the Rockies have long sought pitchers with strong fastball/changeup arsenals. Sure, Chase Field isn’t Coors Field, but as we discussed some time ago when it comes to batted balls, the Diamondbacks’ home is the next closest thing to playing at a mile up. Maybe that makes changeups slightly more important in Arizona than they might be anywhere else, Denver excluded.

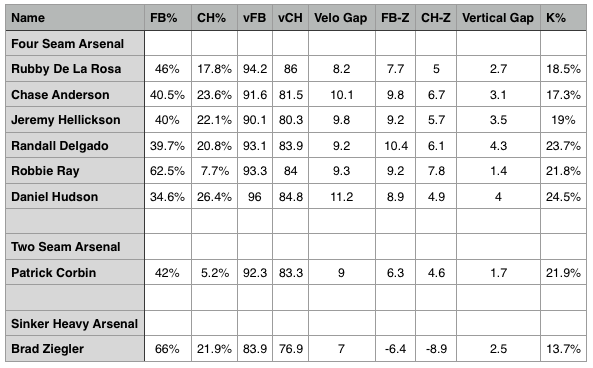

So let’s have us a look at the Diamondbacks’ pitchers in 2015 and see how they stacked up under this same microscope in hope of shedding some new light on changeups playing off of fastballs.

In the four-seam category, only Randall Delgado gets close to the league average in terms of fastball/changeup vertical movement gap. Daniel Hudson is in the ballpark, too, but he’s almost a half-inch off the pace, which is the difference between a whiff and a grounder with a chance to get through the infield. Chase Anderson is known for his fantastic changeup(s) but it looks like he’s benefitting from the velocity gap more than the movement gap. The most surprising result is that of Robbie Ray‘s. He’s had an effective changeup since he was in the minors and it’s the breaking ball that gives him trouble. Somehow, he’s been able to find a way to be successful with the changeup despite the pitch’s vertical movement as compared to his fastball.

Patrick Corbin relies on the two-seam fastball and doesn’t get much vertical separation between it and his changeup. The nine mile-per-hour gap is nice, but just as we observed with the group of two-seam heavy pitchers, the vertical gap is small and, as we know, he gets his strikeouts with the slider. While I’ve been wishing for his change to come around for a couple of seasons, it doesn’t look like the pitch is all that impressive yet. Brad Ziegler is, well, totally weird. There are reasons to just omit him altogether, but the movement gap is notably small and he doesn’t get many whiffs. Then again, that probably has far more to do with his mechanics than it does the vertical gap in pitches.

[Andrew Chafin was omitted because he doesn’t throw very many changeups. Same goes for Shelby Miller. Josh Collmenter was omitted because he relies on a cutter and there just aren’t enough guys throwing one all the time to establish a baseline. Same goes for Zack Godley.]

Closing Thoughts

There’s a trend league-wide, that much is clear. It breaks down somewhat when we’re only looking closely at seven pitchers and a submariner. If anything, we can definitely tell that no D-backs pitcher has an elite gap between their fastball’s vertical movement and the vertical movement of their changeup, except:

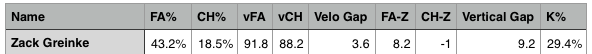

Zack Greinke has the fourth-largest vertical movement gap between his primary fastball (four-seam) and his changeup. If you want to see what that difference looks like, because let’s be honest, we cringed when we saw him pitch against the Diamondbacks last year, this is for you:

Four Seam Fastball

Changeup

Both pitches are late in the game, but you’ll notice that the fastball stays mostly true while the changeup has some serious sink. Freddy Galvis swings right over the top for a reason. This is what an elite fastball/changeup combination looks like. You won’t see much of it in Arizona next year, but when you do, it’ll probably be when Greinke’s on the mound. Even if the staff as a whole is behind the curve, Greinke’s well out in front. Should someone not-named Greinke have their changeup appear to take a step forward in 2016, the gap between fastball movement and changeup movement will be the first place to look.

3 Responses to Fastballs and Changeups and Diamondbacks

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23

Congrats to @OutfieldGrass24 on a beautiful life, wedding and wife. He deserves all of it (they both do). And I cou… https://t.co/JzJtQ7TgdJ, Jul 23 Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

Starting 2022 with a frigid dog walk sounds just lovely https://t.co/xoLZSZBpGp, 24 hours ago

Starting 2022 with a frigid dog walk sounds just lovely https://t.co/xoLZSZBpGp, 24 hours ago I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30

I’ll never forget seeing Kyle Seager at the Scottsdale Fashion Square one March with his family and thinking “damn,… https://t.co/uapNYdsU2a, Dec 30 Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29

Big dogs. Bigger trees. @ Avenue of the Giants, Nor Cal https://t.co/YAdxcE1t1p, Dec 29 Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27

Old friend alert https://t.co/7HQjiyBWTB, Dec 27 Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Death wish https://t.co/XJzcMkNPTy, Dec 26

Powered by: Web Designers

I’m not convinced that Chase Field is as bad a “breaking ball” park as you think. I’ve sat in those stands and watched way too many pitcher succeed with devastating breaking balls. Randy Johnson and Patrick Corbin’s sliders are at the top of that list. I also remember Ubaldo Jimenez, Tyson Ross and Jake Peavy dominating at Chase Field with their amazing breaking balls.

I couldn’t help but notice Robby Ray’s low fastball/change-up differential. More evidence he needs to develop his secondary pitches and become more than just a fastball pitcher.

I was amazed at Greinke’s fastball change-up differential. This is the reason I am am confident that he will still be successful even in the late years of his contract. His ability to change speeds will allow him to be successful even if he has a drop in velocity as he gets older. He has the kind of stuff to succeed up until the age of 40.

Jason Schmidt killed the Diamondbacks with his cutter. I watched him at Chase (BOB then)twice in the early 2000’s and his cutter would drop off the end of the world and leave all the Diamondback hitters looking pretty foolish.

[…] look back at some changeup studies showed that a wide gap between fastball velocity and changeup velocity is beneficial. Maybe this is the […]