What Does a Top of the Order Hitter Look Like?

Right off the bat, I should say that this post was clearly spurned by the recent trade that sent five players packing bags and heading to either Arizona or Milwaukee. I’ve never been to Milwaukee, but I get the feeling that I’d rather head to Arizona than Wisconsin in general. Besides, they sell cheese and bad beer everywhere these days. Anyways, it was Dave Stewart’s quote about Jean Segura that lead me here.

“Jean Segura is a guy we can hit at the top of the order if we chose to,” Stewart said. “With the opportunity to make a move like that, we felt we would do it.”

I spent some time the other day discussing Segura in detail – notably his track record and approach. His struggles make him questionable as a top of the lineup hitter, mostly because the leadoff hitter receives the most at-bats of anyone on the team and, presumably, you’d like to give your best hitters the most at-bats. Segura is projected to have the second worst offensive output of any starter on the team. When you think about it like that, like I do, that’s not a guy I’d choose to put up near the top. And it’s been said and bears repeating – Stewart says these things in large part to put a PR spin on the deal. GM-speak is different than scout-speak or manager-speak or analyst-speak or whatever-speak. He’s got a job to do and although I don’t really understand it, part of that job is spinning transactions no matter what. He’s got that part down pat.

But back to the whole top of the order hitter thing: what does that even mean? What does a “top of the order hitter” look like? I started with the obvious: speed. It’s long been known that teams like a guy who can run at the top to “set the table” for the actually good hitters, or “RBI guys.” We know what RBI’s are and aren’t, but speed at the top seems like the sort of pervasive thing that’s widely accepted in the baseball community.

Another attribute that’s likely to come up is contact. No one wants their top of the order guys striking out 28% of the time. That’s a lot of wasted chances and not a lot of table setting. Traditional baseball also covets a player who can control the bat and hit behind the runner from the two-spot if the leadoff guy reaches base. It might be a ground out, but at least it’s a “productive out.” There’s something to that – advancing runners is good. Given Segura’s batted ball distribution, we don’t have to use our imaginations here all that much.

For those of us in the more progressive baseball community, we tend value on-base percentage since getting on base is a really good way to end up scoring. Unless you’re gonna go yard at a prolific rate, it all starts by getting on base. So getting on in front of the team’s good hitters makes a lot of sense. “Get ’em on, get ’em over, get ’em in” only works if you get ’em on to start with. When you have guys like Paul Goldschmidt and David Peralta coming up, you want guys on base ahead of them. That sounds like a good recipe to me.

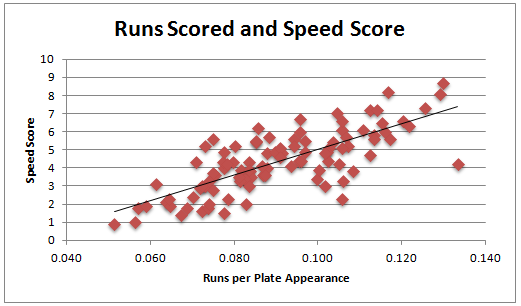

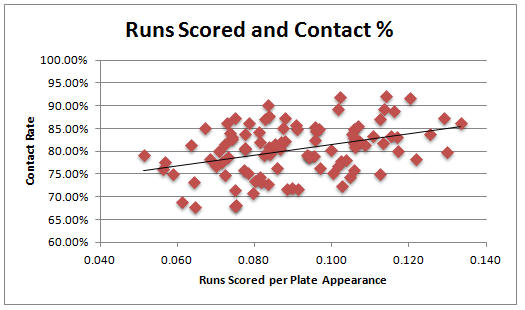

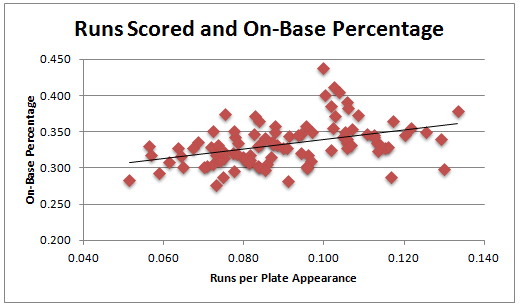

So I decided to run a little test. You know, head to the numbers. I sampled the National League’s qualified hitters from 2013-2015 and figured out how many runs they scored per plate appearance. I took out runs scored via hitting home runs so as not to over value players who produce a lot of their own runs. Then I correlated the results to Speed Score, Contact Rate and On-Base Percentage. The results were mostly what I expected.

Hey look, the faster the player is, the more runs he scores! It must be really nice to be really fast, right? Well, no, actually. There’s a massive amount of selection bias here. Remember, managers often construct their lineups with fast players at the top of the lineup. Guys at the tops of lineups score a lot of runs in large part because good hitters hit next. The fastest players did score the most runs, but it wasn’t necessarily the case that they scored the most runs because they’re fast. So let’s try elsewhere.

Okay, contact rate shows some effect. The correlation between contact rate and runs scored was .378, which is a relatively strong correlation. This makes sense given that it’s hard to get on base and score runs if you can’t make contact. The more contact you make, the better your odds of reaching base on a ball in play (provided the contact is in the normal range of batted ball velocity). There may be some bias in here as well as contact guys tend to hit towards the top of the order for reasons we’ve already spoken of, so maybe we have to make a small adjustment here. Still, there’s some effect.

Okay, so we notice right away that on-base percentage has a slightly stronger correlation to runs scored than contact rate did. For the record, the correlation here is .410, stronger than what we just saw above. Again, this makes intuitive sense given that getting on base is a key part of scoring runs. There are teams who have prioritized this at the top of the lineup card. Kevin Youkilis used to bat leadoff, for crying out loud and if there’s one thing we that public took away from “Moneyball” it’s that walks are almost always good (although that was definitely not the point of the book). The selection bias here is surely less prevalent than with contact rate, so we don’t have to make the same adjustment, which likely widens the gap between contact rate and on-base percentage as they relate to runs scored. I’m sure there’s a more advanced way to do this study, but on first glance, it looks like on-base percentage trumps contact rate in this regard.

Ryan did some good work on this topic just last week when he noted that A.J. Pollock should leadoff against lefties and Jake Lamb should lead off against righties. This was before the whole Segura thing but I’m going to go out on a very short limb and suggest that the recent trade doesn’t change the math very much (especially since he had Chris Owings batting 7th or 8th and he and Segura aren’t all that different in terms of skill sets and profiles). With the D-backs’ offense tied to Goldschmidt, Peralta and Welington Castillo (and *knocks on wood with crossed fingers* Yasmany Tomas), getting guys on ahead of what is still not the deepest lineup in the NL can make a world of difference. Squeezing every run out of this group is imperative given the razor-thin margin for error in Arizona this year.

Circling back, Segura does make a lot of contact and he’s a plus runner. He is Trumbonian in terms of getting on base, though (and without the #DINGERZ). Should that put him near the top of the lineup? No, that’s clearly not the place for him. He doesn’t even have a split to utilize against left or right-handed pitching. He’s been balanced and not that effective. Should he hit second just so he can try to push Pollock over once a game? That’s also a “no” because he will often fail to move the runner in that instance and then you’re left with three more relatively paltry plate appearances in front of the heart of the order. I can’t say for sure if Dave Stewart sees this, but I’m guessing someone somewhere (although probably not here) has pointed this out. Until I see a lineup card in April, I’m chalking this up to GM-speak. I hope.

5 Responses to What Does a Top of the Order Hitter Look Like?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04 RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

RT @JCGonzalezOR: Special thanks to @HillsboroHops for hosting a LatinX community outreach and visioning session. This organization i… https://t.co/OxmEgwOpEh, Dec 08

RT @JCGonzalezOR: Special thanks to @HillsboroHops for hosting a LatinX community outreach and visioning session. This organization i… https://t.co/OxmEgwOpEh, Dec 08 Old friend alert https://t.co/xwSHU0F8Hn, Dec 08

Old friend alert https://t.co/xwSHU0F8Hn, Dec 08 Every once in a while you get a beer that's just a little off... Usually happens to me at airports., Dec 07

Every once in a while you get a beer that's just a little off... Usually happens to me at airports., Dec 07 If Pollock doesn’t sign with a team that wears red uniforms I’m going to be really disappointed. Working theory: Se… https://t.co/zHn9DqzEiD, Dec 07

If Pollock doesn’t sign with a team that wears red uniforms I’m going to be really disappointed. Working theory: Se… https://t.co/zHn9DqzEiD, Dec 07 The work here by @Britt_Ghiroli is splendid https://t.co/c8tSq0vw3T, Dec 07

The work here by @Britt_Ghiroli is splendid https://t.co/c8tSq0vw3T, Dec 07

Powered by: Web Designers

I took a brief look at the runs scored by the lead off hitter(s) for the top 4 teams in the NL in runs scored, to see if “table setter” correlates to anything. None of the lead off hitters leads his team in runs scored. Only Blackmon in Colorado came close and is a full time lead off hitter. The other 3, D’backs, Nationals and Pirates, used multiple lead off hitters. At best, they scored the 3rd most runs on the team, but weren’t anywhere near the top run scorers. Instead, there were multiple players who scored well for the team. For the D’backs, obviously they didn’t lose their one and only lead off hitter when they traded Enciarte, but they didn’t last year, and don’t this year need an dominant lead off hitter/table setter in order to score a lot of runs. Segura can be one of several different lead off hitters to set the table for another prolific scoring offense. Scoring wasn’t a or “the” problem last year and it won’t be this year either. Starting pitching is the key. So the Segura trade need not be analyzed to death as if it’s a make or break part of the D’backs’ off-season dealings. It’s really inconsequential. The D’backs will be just fine with Segura in the infield and lead off mixes.

Yes, I feel like the trade was mostly about moving Aaron Hill. Everyone knew we didn’t want him anymore, and you don’t want that awkward energy hanging around the club going into spring training. I already saw videos of Hill working out at our spring training facilities and that’s just unfortunate, especially because he’s such a good guy. Addition through subtraction, then, on the human level if not on the statistical level.

Segura is like one of these lottery tickets the FO seems to like — maybe he emerges (again?) in Arizona, maybe he doesn’t. Yes, we paid for him, but what we paid wasn’t worth that much, to us at least; we can debate whether our FO values assets correctly or not. And now, instead of Hill’s aging-out narrative, we have a story about personal and professional redemption to carry to the spring. I mean, who won’t pull for a guy trying to bounce back from real tragedy (except for Ahmed and Owings of course).

But, no, he probably should not bat at the top of our order unless his OBP takes a huge leap upwards, so thanks for making that *more* obvious.

Self described progressive = turn around and walk away.

If you knock on wood with fingers crossed, I think they cancel each other out.

I think Stewart was implying that if he returns to close to the player that he used to be in the first half of 2013 for the brewers, then he could be a top of the order hitter, which is true. I hope to all that I hold dear that he was not talking about the Segura that stunk it up for the last two years being a top of the order hitter.