Jake Lamb Stance Adjustment Less About Weaknesses, More About Strength

I say this in the most sober way possible: I’ve probably given up the claim of objectivity when it comes to Jake Lamb. But my “appreciation” was born out of something objective: an evidence-based belief that he’d reach his imagined ceiling, and that the (very few) players of his ilk get short shrift in the majors. The guy looked like a special kind of understated beast. He still does — and now he’s doing something new that could break the cage.

Mike Ferrin kindly tipped us off a few days ago to a change in Lamb’s stance—the hands were lower, Mike said, and the swing path looked shorter as a result. The change is pretty dramatic. See for yourself; this first clip from August 27th last year was on a fastball middle-down in the zone:

Lamb tilted the bat a ton to go get that one; Statcast had it at 109 mph, and it seemed to come off of the bat with a fly ball launch angle. The bat was so tilted, though, that it was a liner right through the infield. I picked that clip because it’s Lamb being Lamb, but also because it was a 3-2 count and his interest in making contact was probably pretty high.

This next one was Sunday, and like in the last clip, it was a fastball middle-down (although not thrown as hard). It was also hit in a similar direction, if with a different launch angle.

Take another look. You can see the difference immediately in Lamb’s setup as the pitcher delivers; Lamb’s knees are a bit more bent, but his hands are a good six inches lower, in line with his uniform lettering instead of his face.

As Lamb loads and swings, it looks like the change disappears. What looks like more of an arm bar from the purple August screenshot probably isn’t; the pitch is ever-so-closer to the plate. The camera angle is also not exactly the same, and between those two differences, I wouldn’t hazard a guess as to a difference in hip rotation. Lamb’s head is down, he’s bent almost the same, etc.

By the moment of contact, though, the difference shows up yet again, and in force. These two pitches are in almost the same location (hence me picking the August clip), but look at Lamb’s wrists:

It’ll be fascinating to see if a swing like this meant lesser exit velo — and we’d need a handful of examples, because exit velo is only partly about the force/speed of the swing (sweetspotting the ball is the rest). But even though the pitch Lamb is hitting is in almost the same spot, in the August screenshot Lamb is clearly at full extension — and in the March screenshot, Lamb has kept his wrists down to keep the bat more level, and done so without short-arming the swing. From the clips, you know that Lamb’s finish is also different; in the clip from a couple of days ago, it looked a little like he didn’t know what to do with it. That part of the swing is more likely to change as Lamb works this out in spring training. It seems very apparent, though, that Lamb is trying to do something different, and that he is doing something different.

So why the change? I can think of a handful of explanations:

- Timing. Lamb’s strength against low pitches extended to breaking balls, which he therefore didn’t see too often. But either from lack of other options or because pitchers thought they could take advantage of his swing, which didn’t keep the bat in the zone for long — he did receive a steady diet of changeups, 15.2% of pitches (that’s top 10 percentile). But I very much doubt this is actually it, because right now it doesn’t look like he’s slowing his bat down, or that the new swing necessarily gives him more reaction time.

- Getting better against lefties (see next section).

- Covering more of the plate (see section after that).

- Loft, and home runs. This is my pick. But that’s partly because of what it looks like, partly because of what the new swing should do, partly because it’s a reasonable change to make, and partly through process of elimination. Back to that at the end.

Is it About Hitting Lefties?

It may be that Lamb was asked to shore up his approach against lefties, against whom he batted .200 in a shamefully small sample of plate appearances (51 — and he still had a .275 OBP). If that’s the case, there’s not a ton we can do here with numbers. It’s a scouting issue. And while I’m no scout, I’ve attentively watched a lot of baseball — it should have more than zero value when I tell you that Lamb’s approach against lefties was something I was very actively interested in last March, and that while he didn’t seem like a strong candidate for a reverse platoon split, it seemed like he’d be fine.

What obscured the picture last March and last season in his smattering of appearances against lefties was that they all seemed to pitch him the same way. There’s something about Lamb’s “Griffey Swing” that made it look like low and away would be a liability. Based on how he turned on that ball down in the August clip above, you can feel in your baseball bones where that impression would come from. Lamb looked like he was holding his own against lefties last year not necessarily because he was doing damage (.275 SLG vs. lefties), but because when he failed, he battled.

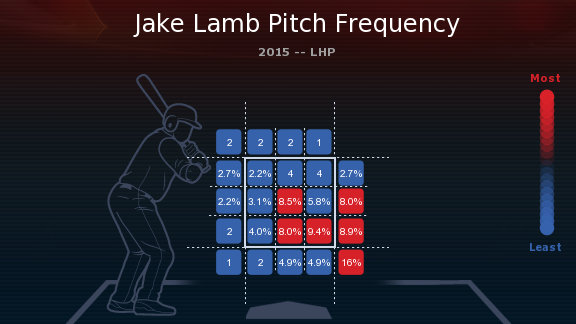

As pitchers wailed away low and away, they flirted with the black… a lot. From ESPN Stats & Info:

Not much to swing at anywhere else. Lamb’s at bats against lefties turned into a waiting game. Lamb was more selective than average against RHP — his 3.91 pitches per plate appearance was a small but significant cut above the 3.82 P/PA average for the sport. Against lefties, though, Lamb had a 4.40 P/PA, “battling” without actually swinging that often. He didn’t even have a high foul rate! Lamb was pretty selective overall. Facing right-handers, Lamb swung 42.7% of the time, which is still very low; against lefties, that swing rate dropped to just 37.5% of pitches, which is flat out amazing. Against LHP:

If a new approach gave more confidence to Lamb to swing more often against lefties, that would probably not hurt, at all. But don’t forget those pitch frequencies. We have no idea what’s happening behind closed doors. But it seems pretty obvious to me, that to hit lefties, Lamb has to do well with the area of the zone (and/or off the zone) low and away. It’s just that he already does that.

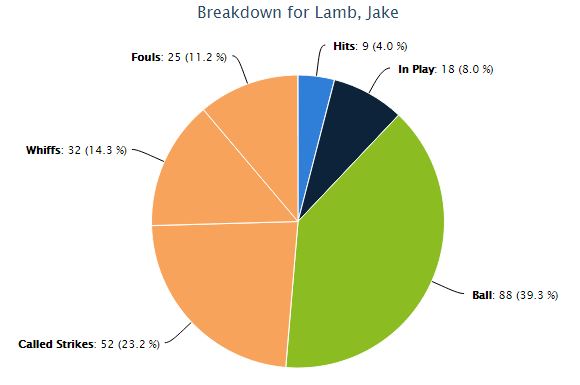

Lamb Already Had Good Plate Coverage

There’s some swing in miss in Lamb’s game, by design — but don’t let his significant strikeout rates fool you into thinking he doesn’t have a strong sense of the strike zone. Among 248 hitters with at least 350 PA last year, Lamb had the 47th-lowest swing rate on pitches outside the strike zone, 26.1%. Of those 248 hitters, 26 were rookies — among whom Lamb ranked third (and one of the two hitters ahead of him was the 28-year-old Korean Baseball Organization import Jung-ho Kang). A big part of hitting the ball hard regularly is swinging at the right pitches, an inference we drew from minor league numbers as something that would play in the bigs — and that also extended to Lamb’s work in the strike zone, where he was still more selective than average.

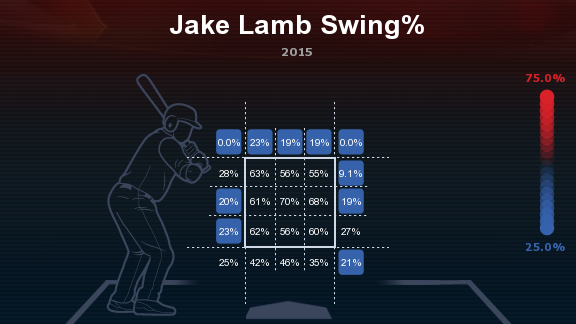

Back in August, Jeff made the case that Lamb should start against fly ball lefties, if not all lefties; even though his batted ball profile has evened out over time, he’s still something of a ground ball hitter, and my (most likely flawed) memory is that a lot of Lamb’s liners tended to be pretty flat, too. As you’d guess from those tendencies, Lamb swung at balls below the zone much more than he did in any other quadrant. From ESPN Stats & Info:

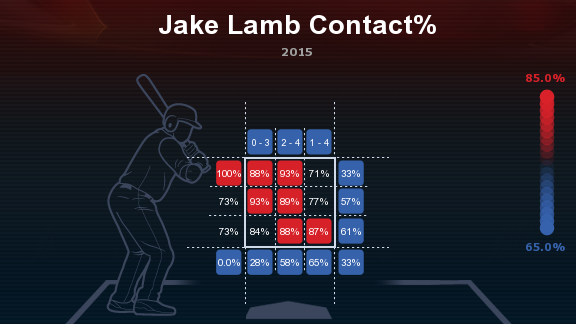

In each of those nine sections of the zone, Lamb swung at very consistent rates that’s not a huge difference between 70% middle-middle and 55% up and away. We might conclude that Lamb’s selectivity had a lot to do with the pitches themselves, instead of where they were thrown. That doesn’t completely translate to contact rate, as you can see below, but 71% up and away is still hilariously good for the worst of the nine sections. Last year, Lamb ranked 5th among the 26 rookies in zone contact rate (89.5%), which is more impressive than it sounds given the violence of his swing. Kris Bryant, for example, had a 75.8% zone contact rate.

If there any spot for improvement, it’d be that up and away area — and it’s worth noting that Paul Goldschmidt became the MVP-caliber hitter we know and love in large part when he started to own up and away while continuing to dominate inside and middle-middle. Every hitter is different, though, and whereas getting lower to the ball might be a thing you’d do to keep from getting hammered low and away, Lamb doesn’t have that problem. He hit a just-fine-and-dandy .241 low and away, and murdered pitches middle-away (.412). Heck, Lamb hit .357 on pitches that were middle-high and off the zone away. He has no problem with reach.

***

Launch angle is the story, as far as I’m concerned. Lamb’s game at the plate has been about hitting the ball hard much more regularly than most major league humans, with a higher batting average on balls in play and a higher batting average overall than you might guess from his strikeout, walk and contact rates. Hits are great, especially in an offense where being able to take a turn at the wheel of the bus seems to make the whole thing work.

Home runs are better, though. Lamb falls through the cracks of the baseball zeitgeist because the thing he does normally means home runs; there are guys like Howie Kendrick and maybe Joe Panik, but everyone else who seems to be able to maintain high BABIPs does so with great foot speed or gaudy home run totals. Maybe he doesn’t need to be weird. Hitting the ball with some loft is not easy — your margin for error is smaller if you’re not matching the ball with swing plane as much. But as we saw in the first clip, it’s not like Lamb was always matching the ball with a more level swing anyway. Much like David Peralta, his gift is to be able to pair swinging with precision with swinging hard, and you can’t put over 30.7% of tracked balls in play at 100 mph or more without barreling the ball more regularly than your peers.

I think this is about getting under the balls he loves to swing at. Note how Lamb’s swing rate on balls down and in was fairly high (for him), but it was not one of his happiest zones in terms of contact rate — and he had a lowly .136 batting average there. Imagine if with just one adjustment, Lamb could hit the ball in the air just a bit more, a bit more often — while no longer swinging on top of those low-inside pitches, and without losing much swing speed. You’d have a monster.

Jake Lamb is a strong man, and this new swing might play to that strength. Stats suggest about as strongly as they’re able that despite low power numbers, Lamb has great talent at hitting the ball very hard with uncommon regularity. We may be about to see that translate to slugging percentage, and to home runs.

Stay tuned.

14 Responses to Jake Lamb Stance Adjustment Less About Weaknesses, More About Strength

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04 RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

RT @JCGonzalezOR: Special thanks to @HillsboroHops for hosting a LatinX community outreach and visioning session. This organization i… https://t.co/OxmEgwOpEh, Dec 08

RT @JCGonzalezOR: Special thanks to @HillsboroHops for hosting a LatinX community outreach and visioning session. This organization i… https://t.co/OxmEgwOpEh, Dec 08 Old friend alert https://t.co/xwSHU0F8Hn, Dec 08

Old friend alert https://t.co/xwSHU0F8Hn, Dec 08 Every once in a while you get a beer that's just a little off... Usually happens to me at airports., Dec 07

Every once in a while you get a beer that's just a little off... Usually happens to me at airports., Dec 07 If Pollock doesn’t sign with a team that wears red uniforms I’m going to be really disappointed. Working theory: Se… https://t.co/zHn9DqzEiD, Dec 07

If Pollock doesn’t sign with a team that wears red uniforms I’m going to be really disappointed. Working theory: Se… https://t.co/zHn9DqzEiD, Dec 07 The work here by @Britt_Ghiroli is splendid https://t.co/c8tSq0vw3T, Dec 07

The work here by @Britt_Ghiroli is splendid https://t.co/c8tSq0vw3T, Dec 07

Powered by: Web Designers

the movement of his hands is probably more about his ability to not catch up to any fb’s last year. If Jake starts catching up to fb’s yes you’ll have your monster.

I don’t remember ever thinking he had that problem, and that’s not computing in my brain, given the bat speed. That first clip from August was 97 per PITCHf/x, and he was out ahead of it.

.352 BABIP on fourseamers last year… just not seeing that as a problem. On the ground too much? Maybe. .300 BABIP on sinkers.

I agree with anonymous. Jake definitely had a “long” swing which kept him from catching up to some pitches.

This was the main reason for the change….

It’s not that I don’t see it — it’s that, that’s who Jake is, and the new swing hasn’t looked “short” to me. The man has bat speed to burn; saying he needs to be shorter to the ball because the swing looks long is a lot like saying Nick Ahmed should play in more, because most shortstops can’t charge the ball well enough to make his positioning work.

I definitely could be wrong, and we’ll get to see more swings and more results soon.

39k’s and 493 ops against power pitchers.

What’s a power pitcher?

How many PA?

Was he actually struggling against those pitchers’ fastballs?

How did the rest of the league do against these power pitchers, in terms of OPS?

ummmm…you kidding me? come on.

Not remotely — if you think those numbers help make a case for him not being able to catch up to any fastballs, then I do really want to understand. The Ks number doesn’t say anything without knowing number of PA, and EVERYONE does worse against “power pitchers,” usually, although I’d need to know what cutoff you were using to be sure. As noted above, anyway, pitchers did send a lot of changeups Lamb’s way — and it’s entirely possible those “power pitchers” were getting him out with changeups, especially if there were a big gap between those and their power fastballs.

I’m not seeing it. On pitches 96+ mph, he swung and missed 16 times to 7 hits (one of them a home run). His BABIP on pitches 96+ mph was .412. His BABIP on pitches 94+ mph was .500!

He swung and missed on 94+ mph pitches 10.6% of the time, which is not more than average. He fouled them off 23% of the time — below average.

From everything I can see, there is no data whatsoever that supports the idea that Lamb had a problem catching up to fastballs. Happy to hear you out, but give me something I can actually work with.

I’m using bbref definition, and that definition there defines power as Power pitchers are in the top third of the league in strikeouts plus walks. Tyson ross really had his number last year. so there’s where to look first. Now, i interpret the power bbref means a good two seam/ or 4 seam, not necessarily 95 plus. It would make sense Jakes high hands means he had trouble adjusting to heavy sink.

Okay, that makes sense — Lamb’s fairly patient approach probably works best against pitchers who pitch to contact, and I agree, bottom of the zone is the issue.

Looks like we’re only talking 97 PA, so I’d be careful drawing big conclusions from stats equivalent to a month’s worth of games. Also, the “power pitcher” definition might over-count lefties, who had a 28.7% K+BB rate last year, a not-small difference with RHP (27.9%).

I think adjusting to heavy sink is right. And I think the new swing is designed to help keep him from beating those balls into the ground — so we’re not far apart.

[…] base and has seemingly made everyone’s “2016 breakout” list. The reasons for that are real: a new swing to compliment a rare ability to square up baseballs and hit them hard. There’s really no telling how much better he can be with these changes, but […]

[…] field, even donating an outfielder’s glove to the cause in the early going. When Jake Lamb changed his swing a bit over the winter, he patterned his approach after Pollock, in part. And Nick Ahmed did the […]

[…] didn’t hit the ball high enough in the air as often. Before the season began, it looked like a change in batting stance would help Lamb loft the ball just a bit […]

[…] philosophy of Bobby Tewksbary, who helped both of those hitters. Sound familiar? Jake Lamb also changed his approach at the plate over the offseason in a similar way, and Lamb, too, was fascinated by the way Pollock loaded at the […]