What the Chase Anderson Repertoire Change, Early Success Means for Shelby Miller

The D-backs have adopted an aggressive old-school approach to building a baseball team. Maybe we should have seen it coming after renowned experimenter Tony La Russa took the helm; you can almost imagine him taking the job as Chief Baseball Officer in part because of some zeal in adopting strategies he wished he could have adopted as a manager. However it happened, the team is treading a path that they haven’t had to share with anyone else. A unique home field advantage plays into things, but the team does deserve a lot of credit, using lots of imagination with position players and evaluating pitchers on results, understanding that we can’t understand every possible thing that can lead to a pitcher’s success — or lack thereof.

But we can understand some things. Armed with lots of available playing time, prolific analyst Mike Fast and a mandate for a long-term plan, the Astros did just that. They used some knowledge about where not-particularly-elite fastballs were most effective, taking a poor man’s Wade Miley in Dallas Keuchel and helping him become one of MLB’s best starters. They were ahead of the curve on useful spin on benders, turning waiver claim Collin McHugh into a reliable starter and snagging a similar pitcher in Mike Fiers when they traded for Carlos Gomez. And as for the overall success of the steady stream of former D-backs lefty relievers they acquired — Will Harris, Tony Sipp, Oliver Perez, and even Joe Thatcher — your guess is as good as mine.

David Stearns left Houston for Milwaukee about seven weeks too late to have Fiers, but his AGM experience with the Astros was clearly a big reason why he was hired to GM the Brewers, who seem poised to follow a similar path. Trading Adam Lind, Francisco Rodriguez, Khris Davis and others over the winter, Stearns got back mostly prospects — also swapping some prospects for other prospects in a handful of trades, which should raise some eyebrows. Despite a November trade for shortstop Jonathan Villar — a player Stearns undoubtedly knew well — he still managed to move Jean Segura in late January for something useful.

Yes, Isan Diaz was plucked from the D-backs organization in that deal, and yes, Diaz is probably worth more to a team with playing time available in the not-too-distant future than he was to Arizona. But RHP Tyler Wagner also had value, and he was a pretty good fit for Milwaukee’s trajectory, which raised some eyebrows (in the Milwaukee media; here, we know Arizona’s penchant for acquiring ground ball pitchers all too well). That, along with the assumption of some Aaron Hill salary, was apparently a price Stearns was willing to pay — perhaps because Chase Anderson was even more valuable.

Even with Segura’s torrid start to the year, I’m not so sure that Anderson was not the most valuable player in the deal. Anderson wasn’t as useful to the D-backs as he probably was to the Brewers, so it’s not that the trade doesn’t make objective sense. But it looked a whole hell of a lot like the D-backs essentially sold Anderson, just as they had sold several other players (and a draft pick) in the previous year. And it looked a whole hell of a lot like the D-backs sold low.

Why? Because it seemed like Anderson’s objective value was higher than his 4.30 ERA last year would make one guess. As part of the D-backs’ ground ball approach, Anderson went with a plan in spring training that saw him leaning on his sinker a lot more. It really didn’t work, and by the end of the year, he was throwing it less — and doing better. And there’s a really good reason: it was lefties against whom Anderson really threw the two-seam, and a fastball with that kind of movement tends to have a very large platoon split:

Chase Anderson’s four-seam fastballs look like jumping fastballs, his sinker has the movement of a rider — and the velocity makes it more like a heater than a rider. Heaters are bad ideas in platoon situations. Yet, even though this data would tell us that his four-seam would be an asset against LHH and his sinker would absolutely not be, he did the opposite in 2015; he threw the “sinker” just 17.7% of the time against RHH, but 29.0% of the time to LHH. Lefties had an average of .231 or lower against all of Anderson’s other pitches, but lefties tuned up the sinker: .424 average, .697 SLG. BAD IDEA. NO MORE SINKERS AGAINST LEFTIES. The four-seam should work.

It’s not that Anderson promised to be an ace if he stopped throwing his sinker to lefties; his other pitches probably would have fared worse without it. But lefties were almost assured of seeing at least one sinker if they went four pitches in a plate appearance, and that’s probably enough for a hitter to sit on it. One change — a decision, rather than athletic improvement — seemed capable of improving Anderson in a very real way, as it seemed to at the end of the season.

What you may not know: the Brewers did have Anderson move away from sinkers, but they also had him get back to a pitch he threw once upon a time: a cutter. He’s at 16.1% cutters now, after tossing a few last September. The fourseam is down about ten points, and the sinker slightly more than that; like the cutter, the curveball has also been thrown substantially more. The early returns are good: a 2.25 ERA in three starts. Anderson’s last outing was his worst, but he still had great command of the sinker, getting it to run in on the low/gloveside corner, of all places. And the combo is clearly the plan: in his last start, Anderson threw exactly 13 fourseams, sinkers, and cutters (along with 16 curveballs and 12 changeups).

After an offseason in which we’ve analyzed Shelby Miller‘s 2015 effectiveness with a fourseam/sinker/cutter combination, I feel pretty dumb for not thinking of that myself (although I did come close). He really is the perfect candidate: he doesn’t throw hard, and as badly as his sinker has done, his fourseam hasn’t fooled anyone. But he’s capable of throwing a sinker reliably, along with that fourseam — and in addition to being a decent option all on its own, the cutter brings with it what we’ve all wanted for Anderson all along: some way to make his other fastballs play up.

Full disclosure: Anderson is still throwing his sinker to lefties, it seems. But it’s still probably too early to take meaning from the welfare of individual pitches against subsets of the batters that Anderson has faced, anyway: the point right now is that the profile is different, in a way that was clearly on purpose. If Anderson can bottle even some of the same lightning that made Miller successful last year with the fourseam/sinker/cutter combination, can you imagine Anderson’s ceiling if he still has a pretty good curve… and an elite changeup or two? That looks a whole lot like a Bronson Arroyo floor — and a Johnny Cueto ceiling.

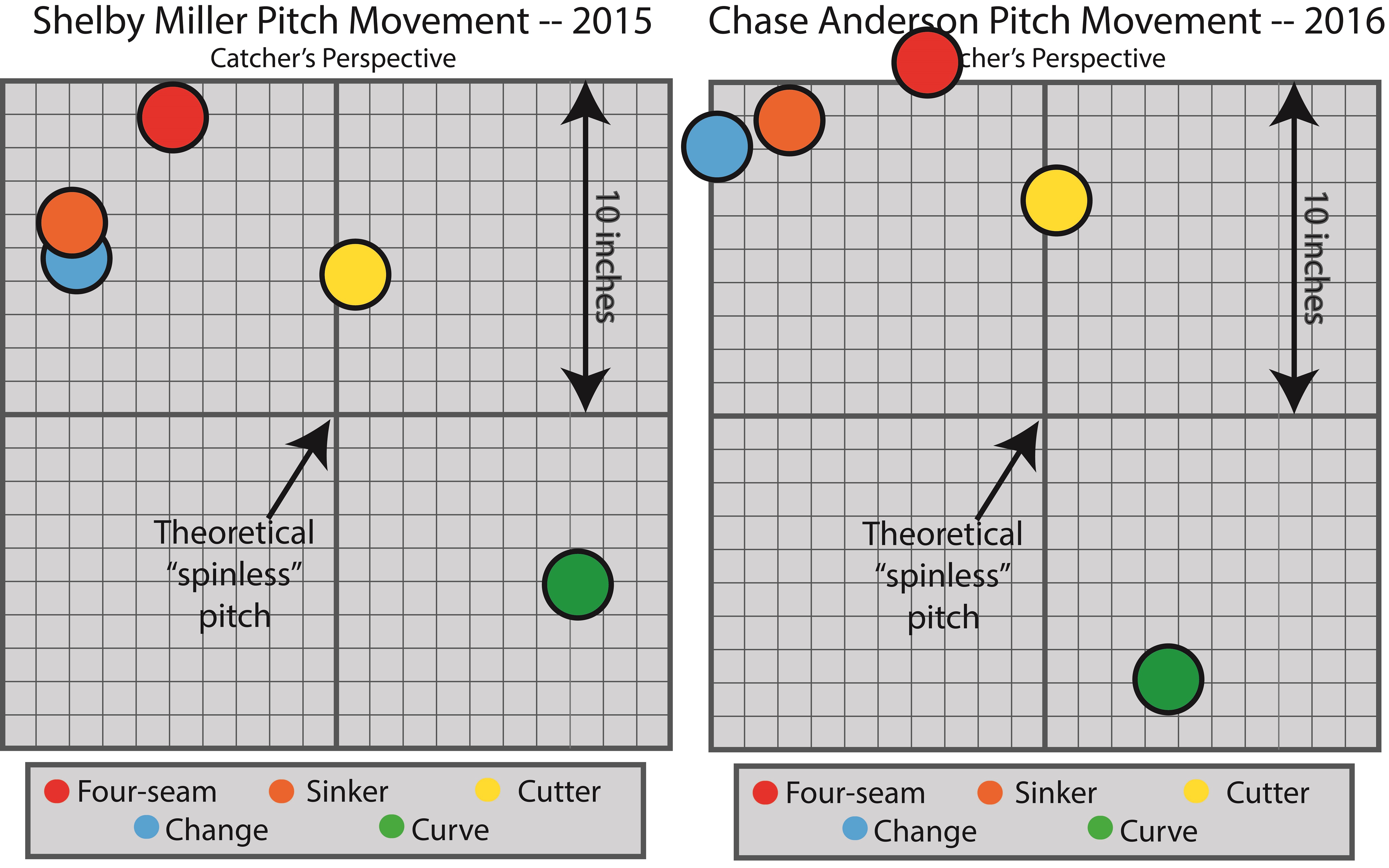

Even with a dip in velocity, Shelby Miller still throws a tick faster than Anderson, a (meaningful) difference of about 1 mph. But check out the movement of Miller’s BABIP-killing repertoire from 2015 with Anderson’s new profile:

A hitter can always guess if he wants, but he may be trying to adjust to several things as he begins to swing: location, movement and speed. With the change, Anderson had speed on his side; but with the possible exception of the bigger-movement version, he wasn’t asking for a big adjustment in terms of movement. For the change and sinker, it was only speed — and while deception is a good thing, I think hitters told us last year that they could pick up the sinker fairly easily. The two-seam and four-seam were virtually identical in terms of speed, and not tremendously different, movement-wise; a baseball is really three inches or so, not the two inches used in the figure.

The cutter could literally add another dimension. For fastballs, you can’t split the two- and four-seam gap, and make an adjustment at the last moment. A swing does change based on location, and changes enough for those kinds of gaps to make a last-moment adjustment much harder. At least, that’s how the theory goes.

***

Maybe the Anderson pitch mix won’t work; maybe he’s just not deceptive enough to even impersonate Arroyo. But we saw Miller’s combination of pitches work for an entire season, with contact management too extensive to be all luck. Miller’s three-fastball combo was a very good idea, it seems. And add the Brewers’ Anderson tweak to add some evidence to the same stack; regardless of whether or not it works, it’s more (smart) people thinking it could work.

Miller was more than just a willing participant in mixing up his repertoire that way; the increased reliance on his cutter in 2015 was the finishing touch on a process that started in 2014, which Miller recalled in great detail this spring while talking with ESPN’s David Schoenfield. Miller moved away from heavy reliance on his fourseam, very deliberately:

Sure enough, he was getting hit harder at the start of the 2014 season, with a 4.29 ERA in the first half. Adam Wainwright gave him some advice: “Waino was the guy who told me a four-seam fastball isn’t going to cut it my entire career,” Miller said.

Justin Masterson showed Miller his grip on his sinker. “We were in Philadelphia one time and A.J. Pierzynski was the catcher that day and I just started toying with the sinker with the grip Masterson showed me and I was getting a little bit of movement on it. I told A.J, ‘Look, if this is decent, I want to start throwing it’ and that game I was getting a lot of ground balls with it.”

We don’t have many details on the delivery tweaks the D-backs worked on with Miller — which did seem to add velocity in San Diego before Miller scraped his hand. Maybe those changes are related, but after averaging 21 sinkers thrown per start in 2015, Miller has thrown just one in three starts this year. He’s been back to throwing his fourseam about two thirds of the time in 2016, and has cut down on cutters and curves a little bit, too, while adding a splitter. The splitter has had about one inch less “rise” and about an inch and a half less arm-side run than the change he threw last year, coming in a bit slower, as well. In his brief time this year, Miller’s 33 splits have done well — just two hits. Everything else has done worse. Miller’s sinker/fourseam/cutter combination last year was the method by which he managed contact; the three pitches were greater than the sum of their parts. Instead of seeing if the same thing would work in Arizona, the D-backs seem not to see it at all.

Maybe Chase Anderson isn’t the best thing since sliced bread, and maybe the discount at which the D-backs seemed to trade him wasn’t egregious. The team tried to “fix” him, and it didn’t work, and they didn’t have time to try again. We can accept all that. But something good came of it: we got yet another reminder that Miller’s 2015 approach probably wasn’t successful by accident. After failing to fix Anderson, it’d be a real shame if the D-backs fail to keep themselves from trying to fix Miller.

One Response to What the Chase Anderson Repertoire Change, Early Success Means for Shelby Miller

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Recent Posts

@ryanpmorrison

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08

Best part of Peralta’s 108 mph fliner over the fence, IMHO: that he got that much leverage despite scooping it out… https://t.co/ivBrl76adF, Apr 08 RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: If you're bored of watching Patrick Corbin get dudes out, you can check out my latest for @TheAthleticAZ. https://t.co/k1DymgY7zO, Apr 04 Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04

Of course, they may have overtaken the league lead for outs on the bases just now, also...

But in 2017, Arizona ha… https://t.co/38MBrr2D4b, Apr 04 Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04

Prior to the games today, there had only been 5 steals of 3rd this season (and no CS) in the National League. The… https://t.co/gVVL84vPQ5, Apr 04 RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

RT @OutfieldGrass24: Patrick Corbin has a WPA of .318 and it's only the fifth inning., Apr 04

Powered by: Web Designers@outfieldgrass24

This Suns matchup comes at a good time for my hometown Blazers #RipCity https://t.co/fQ45wdfQUk, 9 hours ago

This Suns matchup comes at a good time for my hometown Blazers #RipCity https://t.co/fQ45wdfQUk, 9 hours ago RT @ZHBuchanan: Our @Ken_Rosenthal spoke to Ken Kendrick about trading Paul Goldschmidt.

https://t.co/O5fHRlyBxD, 16 hours ago

RT @ZHBuchanan: Our @Ken_Rosenthal spoke to Ken Kendrick about trading Paul Goldschmidt.

https://t.co/O5fHRlyBxD, 16 hours ago RT @CardsNation247: We have a good show lined up for tonight. Leading off is our friend of the show @buffa82 followed by Jeff Wiser… https://t.co/eltZC0uvyg, 16 hours ago

RT @CardsNation247: We have a good show lined up for tonight. Leading off is our friend of the show @buffa82 followed by Jeff Wiser… https://t.co/eltZC0uvyg, 16 hours ago RT @juanctoribio: To piggyback off the @ZHBuchanan and @OutfieldGrass24 that the #Rays were involved in the Paul Goldschmidt sweepsta… https://t.co/spg9x7X1L5, 16 hours ago

RT @juanctoribio: To piggyback off the @ZHBuchanan and @OutfieldGrass24 that the #Rays were involved in the Paul Goldschmidt sweepsta… https://t.co/spg9x7X1L5, 16 hours ago RT @OJCarrascoTwo: Read this from the world famous, @OutfieldGrass24 https://t.co/cHUie1I5Le, 16 hours ago

RT @OJCarrascoTwo: Read this from the world famous, @OutfieldGrass24 https://t.co/cHUie1I5Le, 16 hours ago

Powered by: Web Designers

[…] The model appears to be ground balls, at least on the surface. For the D-backs in this span, Ziegler has maintained a 70.1% ground ball percentage — and Webb recorded a 64.1% GB% that was every bit as extreme, in the context of starters. Ground ball percentage is one variety of contact management, because in addition to avoiding (very-hard-hit) home runs, one doesn’t just get lots of ground balls at those rates — one gets lots of weak ground balls, the way fly ball pitcher Tyler Clippard will undoubtedly rack up popups. But ground ball (and fly ball) extremes are not the only kinds of contact management. Launch angle is great; preventing hitters from reliably “barrelling the bat” is also great. And it’s the latter thing that the D-backs acquired in Miller, and what they paid for in Greinke. It’s what has made Johnny Cueto great and Mike Leake decent. It’s what’s given Ian Kennedy a career, and made Livan Hernandez a legend, and what now gives Chase Anderson hope. […]